One of the things that I see often (and I believed when starting woodworking) was that Stanley original irons weren’t very good. On one of the US forums, there was constant drumming of “good” steels like A2 and how poor old steels were because they were made with little control, and then later not that well compared to the “modern” steels we have now.

This kind of statement is generally nonsense, but it’s hard to tell when you’re first starting out. It is true from what I’ve seen that stanley didn’t chase abrasion resistant steels with the exception of some M2 (or similar alloy) plane irons in Tasmania. The reason they probably didn’t (And older makers didn’t adopt alloy steels) is because an experienced user doesn’t gain anything with them, and quite often, the balance of sharpening and use goes south as grain size increases. With few exceptions, adding carbides increases grain size (Those exceptions are steels like AEB-L, CPM 3V and matrix steels like YXR-7 in japanese tools. Even YXR-7 is often wrongly referred to as HAP40). Matrix steels are generally fine grained steels that are lower in carbon but tolerate very high hardness for their carbon content. They’re out of our scope here, as I don’t know of a way to harden them in the open atmosphere, and they will proportionally match wear and sharpening.

But, for a while, I’ve suspected that Stanley chisels and planes are probably softer than a lot of modern steels by choice. The hobbyist crowd and misleading ad copy come along and refer to stanley irons without having a clue what the professional market would’ve wanted. Site sharpenability without a grinder was almost certainly a need. If you took 61 hardness 3V or 67 hardness YXR-7 to a site with no grinder, you’d end up regretting it.

I’ve also seen plenty of references to Stanley steel as O1. I doubt any of it was. The laminated irons were almost certainly water hardening steel (otherwise they’d be a problem to forge weld to the soft iron).

A Discovery – Carbides

In making 26c3 chisels, I figured it might be a good idea to make some knives and plane irons. It turns out that the plane irons are wonderful, but they offer no increase in edge life over something like 1095 (for some reason, the irons are harder, but as is the case with japanese steels – the edge life doesn’t improve). Below are pictures of a few irons – take a look at the edge. These are generally 300x optical and the carbides are just a few microns each.

Hock O-1 – Just a few Carbides and Very Small (probably 0.9 or 0.95% carbon)

This Hock iron shows the same carbide pattern that my own made starrett O1 irons show – as in, very little. Starrett is 0.9% carbon and I can imitate hock’s irons or give them a slightly better temper (and take a point or so off of hardness where they seem to work better in general use).

1095 – Also likely 0.9-1% carbon – Almost No Free Carbides

wear resistance is just baseline, but look at the uniformity of the edge as it wears. In my experience, this generally leads to less chipping in use and fewer lines on work

26c3 – 1.25% Carbon – Plenty of Free Carbides

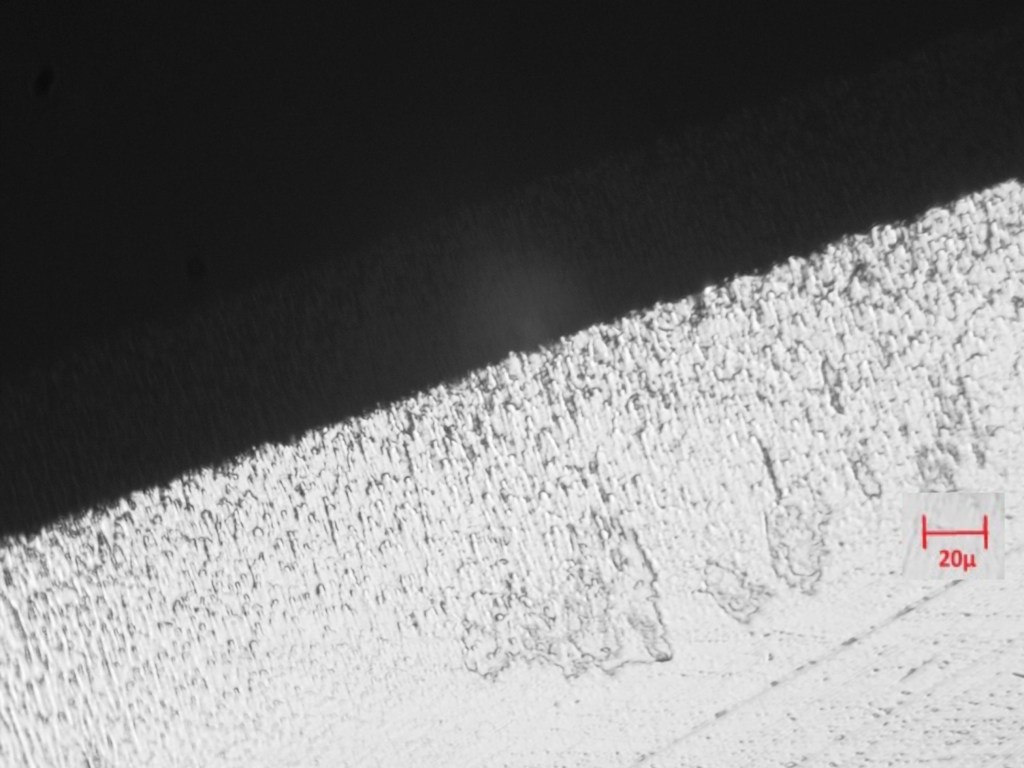

Stanley Sweetheart – Laminated – A Surprise – Carbon Unknown

Fairly significant carbides appear after some edge wear! Unexpected!

And- XHP (the same or similar to V11 – high carbide volume, but lots of surplus Chromium)

When we examine the pictures above, the carbides appearing suggest whether or not there is surplus alloying. For high carbon steel with little in terms of additives, the free carbides are carbon. They’re not that wear resistant, but the matrix remains reasonably fine and toughness can be kept. As carbon increases, peak hardness also increases and there is some loss of toughness.

These terms and the results are not well described in the woodworking community. Claims of increased hardness, toughness and longer edge life are combined constantly, and they’re rarely accurate. Maybe never. What beginners generally think is “difference in steels” is the chosen temper. So, stanley plane irons are described as substandard (perhaps some in the 1970s or so are lower carbon – I will test that later as I’m sure I have some – the laminated iron above has a pretty strong surplus of carbon)

An Opportunity Comes from This

If my suspicions are correct, the stanley iron is fine grained – there’s little toothiness to the edge in wear – and it has peak hardness in reserve and will make a great iron for bench work at higher hardness (it was already a great iron, but I’ll temper it like modern irons are tempered).

I suspect at 400F temper, it will be harder than a comparable A2 or O1 iron (V11 is more or less around the same hardness at 400F temper).

So, I ran it through the heat treat cycle that I generally use for anything water or oil hardening and, in fact, it does come out very high hardness. I would guess it’s 63 hardness or so, and the feel on the stones is water hardening steel, not 52100 or anything of the like (definitely not O1). The pictures suggest and the performance in hardening also suggest that it’s a plain steel with surplus carbon – maybe something like 1.1%, give or take.

Now, for the rotten part – this iron is laminated. I didn’t know it was. The behavior it had in heat treat was worse than any I’ve seen by a factor of 10 when dealing with solid steel irons (even vs. 1095, which is warpy). The lamination is probably not constant thickness and I didn’t know why it was so poorly behaved, so after hardening and tempering, I hammered it on the anvil – this is risky, but at this point, I still didn’t know it was laminated and I was ready to write it off, so it got abused a little. I would suspect stanley has rollers or something that these irons run through right out of the quench, just as files are straightened quickly – I don’t have any such setup and didn’t want to concede hardness by hammering when it was still warm. There *is* a short window after quench where you can bend or straighten things (it’s very short) if you don’t get too rough – I hammered a little then and a lot more after tempering. Point of this is that there’s probably an industrial process to deal with the warping just as there is with files, so these laminated irons may not be the best candidate for rehardening.

I generally use an india stone and a washita stone to sharpen, and if needed, buffer or compound on wood – why? It’s far faster than modern stones. It’s faster still even on V11 – as long as someone is freehanding, and on everything, the thin film of mineral oil has translated to no rust on any chisel or plane iron in eons (it was a constant problem in my garage shop when I used waterstones, and flattening stones, wiping irons with oil -that’s a farce).

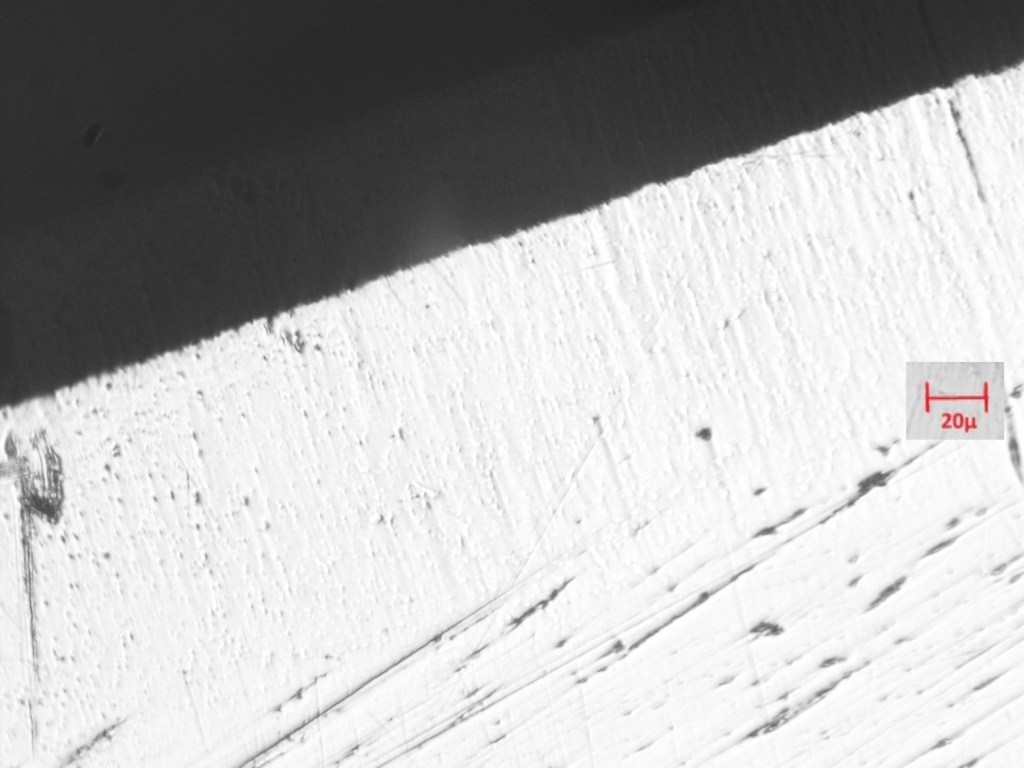

At any rate, plain (mostly iron and carbon with other additives not floating free in the matrix) high hardness irons will take a finished edge off of a washita and leave no perceptible burr, but without having toothiness. Here’s what this iron looked like straight off of india and washita at 150x.

When you sharpen further, or spend more time, the little nits at the edge there will be gone. I didn’t bother to push things further – this is easily an equal of an 8k waterstone. I used the buffing wheel to lightly strop, and this is the resulting shaving thickness.

There’s a lot left in the tank for this iron at its new hardness (sans crack!) – as in, 20 seconds with a honing compound on medium hardwood would make a much finer shaving than the one above. I finally figured out that this iron was laminated when cutting its new bevel – and I have two more sweetheart irons. Sadly, most of my original stanley irons went out loaded on bench planes when selling to save the “good” modern ones. I wish I hadn’t done that, but who knew?

This test is worth repeating with an iron that is solid and that will behave better. I suspect we’ll see the same and I’ll post those results. That is, that the irons themselves have much higher hardness potential and Stanley didn’t skimp on carbon (higher carbon generally does result in a more crisp fine edge – if that doesn’t seem like it could be true, find a 5160 knife at some point and see how good the edge taking is. A little surplus carbon over 0.75% (which is about the most you’ll get in solution so there is no free carbon) leads to lower toughness which to a point, actually leads to better edge behavior. If you’re going to have small damage, the last thing you want is an iron that has a burr that will tear the edge or propagate more deflection – so clean departure of damage is a *good* thing.

How good is the surface left on a cherry edge by this initial “utility edge?”. Note the reflection -the wood is, of course, unfinished. As mentioned, there’s more in the tank than this – but for practical purposes?

So, what did we learn?

- There’s no lack of quality in the steel that stanley used in this laminated iron, though it’s probably not practical to reharden them without developing a process to remove flatness issues out of the quench VERY quickly.

- the hard bit in the laminated stanley irons is *not* O1 (which isn’t a surprise – why would they have spent the money for diemaking steel in thin strips back then?)

- These irons have surplus carbon, leading to the potential for very high hardness when quenched and tempered in the “sweet spot” (375-400F temper for most plain steels). That sweet spot being for woodworking, not for lawn mower blades.

- You can hammer laminated irons to flatten them somewhat, but not as much as I did – you’ll risk cracking

- Follow-up with a solid iron is worthwhile – I’ll locate one, give it an initial wear test to see if there are surplus carbides in the matrix and then reharden

Is there really a practical gain here? I don’t think so, we’re just trying to get truths instead of rumors or suppositions. For the average person starting out making tools, dealing with O1 will be much easier and you can get good results in vegetable oil with it and less warping. You can ignore most of the pundits who tell you that you can’t make an iron as good as a commercial iron – it’s nonsense. You can compare the picture below of the “house iron” to the hock O1 iron above. Notice the carbide volume and overall look – not much different. If you achieve good high hardness and temper to 350F, the iron will be completely indistinguishable, but you will also appreciate in “real work”, tempering around 375-400F – the iron will resist chipping better and sharpen easier without giving up functional ege life.

“Later That Day”

I went through my pile of irons to see if I had any earlier stanley solid irons. I think I probably don’t. That’s OK (I have two more laminated irons, but not interested in cracking them at this point or figuring out how to get them to stay flat through temperature changes).

So, I took the iron that I had in the plane and noticed that the way the crack and another small crack were oriented, they’d do nothing to prevent me from making left and right marking knives. I refer to these as “dump” knives – knives made of things you’d throw in the dump otherwise. It occurs to me that there’s plenty of times that I’d love to have a wharncliffe-ish (like chip carving style tip) knife laminated with a very hard layer.

See the “dump knives” at the bottom. These can be cleaned up further later, but they’re a good opportunity to learn about geometry. I want them to hold their edge well but not have too much wedging force when cutting, and the tip of these will do marking against a rule or square (perhaps even cutting with something like leather). Most carving knives (chip carving, marking, etc) will not be close to the quality of these as far as cutting, fineness and strength. I don’t know why – you can beat most cheap little knives on the market (about $25 or so) with just a scrap of O1 steel. These irons at high hardness should make a marking knife at least as good as the best of the O1 irons and the high hardness will make them crisp. The fine grain makes them relatively tough for their high hardness.