Yesterday, I posted about a laminated Stanley iron and my surprise at just how high carbon the iron is. It was not well behaved in rehardening, but the ultimate finding was that with routine 400F tempering and a fast oil (and good technique), the iron yielded very high hardness and it’s closer to a Japanese white steel than anything else (albeit, the carbide density looks more like a white II type steel).

So, looking for a solid iron from a “good” era of stanley tools, I found that all of the good-shape irons that I have are laminated except for a type 20 iron from a later 6. This irons are notoriously bad, but in my experience, they feel like they are slightly lower carbon and just tempered soft. I don’t know what Stanley’s market was in 1960, as in, who they were aiming for – but I can imagine that few planes were being sold for fine bench work. Regardless, I have a soft spot for types 20 and have three of them. Once they’re flattened, they work wonderfully. I’ll post a flattening process at a later date – it’s useful if you’re going to work entirely by hand as it speeds dimensioning and you can rely on the plane to communicate when something is flat.

The Conclusion for the Type 20 Iron

Since my posts go long, I’ll tell the findings first, and then the details. The type 20 iron (in this case, one with sharp corners and not rounded corners) is solid and not laminated (no surprise), it does not have surplus carbides appearing in the wear matrix (so it’s likely something around 0.9% carbon or below – I would guess a little below that based on resulting hardness), and when it’s given the standard routine and double tempered at 400F, the resulting hardness is good, but well below the old laminated iron. I would estimate it at 60 on the C scale as the india stone hones it readily but it hones finely on a washita and has excellent behavior.

It won’t be a long-wearing iron compared to anything with abrasion resistance, but it hones well, takes a fine edge, holds it and would probably be a better iron for someone working entirely by hand than something like A2 or V11 (because in heavier work, just the course of regular honing should keep the edge free of damage). In nearly all cases, a modern iron with chromium in it in significant amounts should outlast this iron all other things being equal.

Now, the Details

You may wonder why I’m rehardening these. It’s really a matter of three reasons. I use the same rehardening process for simple steels every time. The process should improve anything that doesn’t have surplus non-iron carbides, and where the iron lands in terms of hardness after a 400F temper is a good indicator of how much carbon is in it. Plan irons are thin, and with fast oil (Parks 50 in this case), it’s not hard to get good full hardness results with them.

Irons that end up with lower hardness (testing with an india and a washita stone – two stones that will give good feedback of how hard a simple steel is), generally do so due to lower carbon. There are often other things in smaller irons, but not in large amounts (perhaps a small amount of vanadium, some small amount of chromium, and in older irons, sometimes tungsten). These change the feel on a well used sharpening stone.

So, anyway – reason 1 is to see what the hardness will be after a standard process. Reason 2 is that I’ll probably like the actual iron better after rehardening (if I don’t, there’s no real hope for it). And Reason 3 is to see how practical it is to reharden.

I would estimate the hardness of the iron in this case to be around 60 on the C scale. I doubt i’m off by more than 1 in any hardness guess with plain steels. I expect off of the stone that we’re not going to see excess carbides unless they look like chromium carbides. The one plain steel that would have excess chromium is a bearing steel, but this doesn’t feel like a bearing steel. So I really don’t know.

The iron is improved for bench work – which is pleasant since it’s such a poorly regarded era – and would now make a really wonderful day-to-day iron. It’d be great if it hit high hardness like the old laminated iron to have a biting sharpness off of natural stones, but it still attains a nice edge and is practical. Why did stanley leave it softer than this? I don’t know. The demands of the market, perhaps, a nod to sharpenability (a softer iron will always sharpen faster and easier, no matter what it is), and maybe margin of error as a chippy iron will yield complaints while one that’s slightly too soft may result only in a few groans. I’m convinced the world of consumer knives is filled with underhardened knives to prevent damage that results in returns from low-experience users as it seems fairly easy to better commercial knives with shop made knives. Even marking knives.

The Initial Edge and Carbides

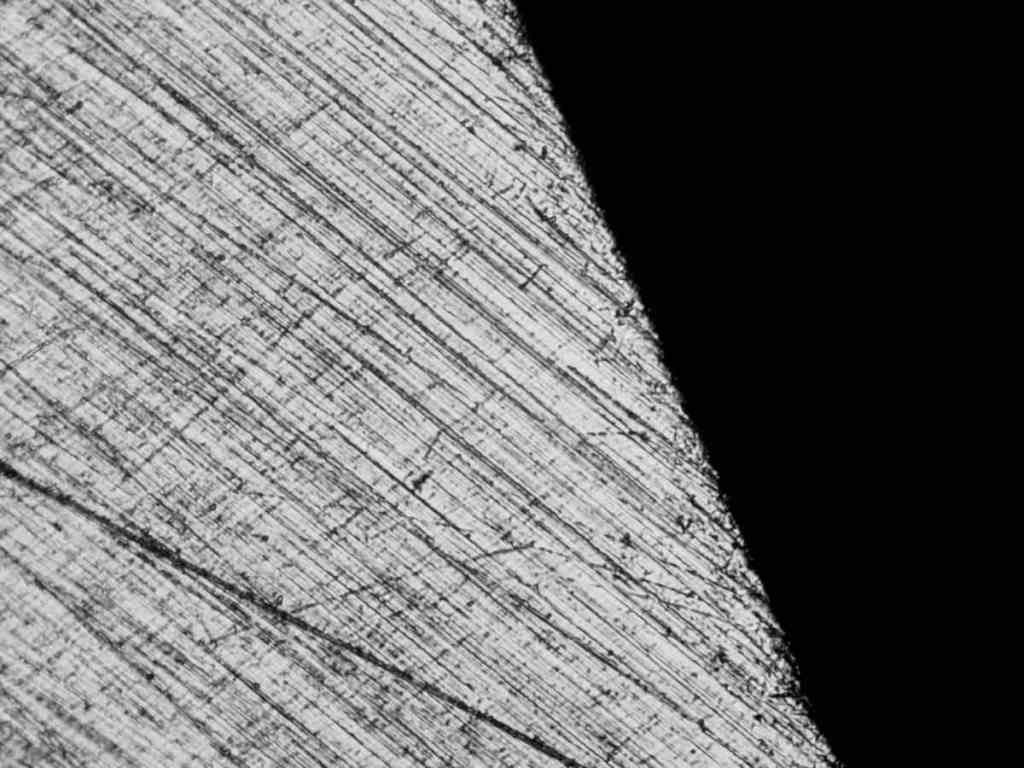

After rehardening, the initial edge comes off of the washita stone relatively fine. Use of this stone is a preference because it’s got such a wide range as long as steel isn’t too soft or far too hard for it (it’s a great tip finisher for japanese chisels, though). A picture of the initial edge is here (you can see a tiny burr left – that burr is probably about a thousandth of an inch long).

A fine edge off of a washita stone – with a minimal burr left. The height of this picture is 1.9 hundredths of an inch, so this burr will depart with first use, but it’s better to remove stropping.

This edge looks a little strange, but it’s safe to say it’s at least as good as an 8k waterstone. Looking at the other anomalies, I flattened this iron quickly after rehardening – the back is near polish but some of those marks are probably dirt or oil.

A comparison of washita to an 8k waterstone will be shown at the end of this as you can’t tell how fine this edge is without a reference.

The thinness of shaving possible from the edge shown above is in the next picture. I didn’t strop the edge, but it’s a good idea to – and doing it very lightly with a very fine oxide on wood or hard leather (or a buffer) is even better.

This is a reasonably fine edge and can be recreated in less than a minute once the iron is dull (which is the advantage of an iron that’s not that abrasion resistant). The steel is fine, there aren’t edge anomalies, overall very pleasant.

Confirmation of Carbides

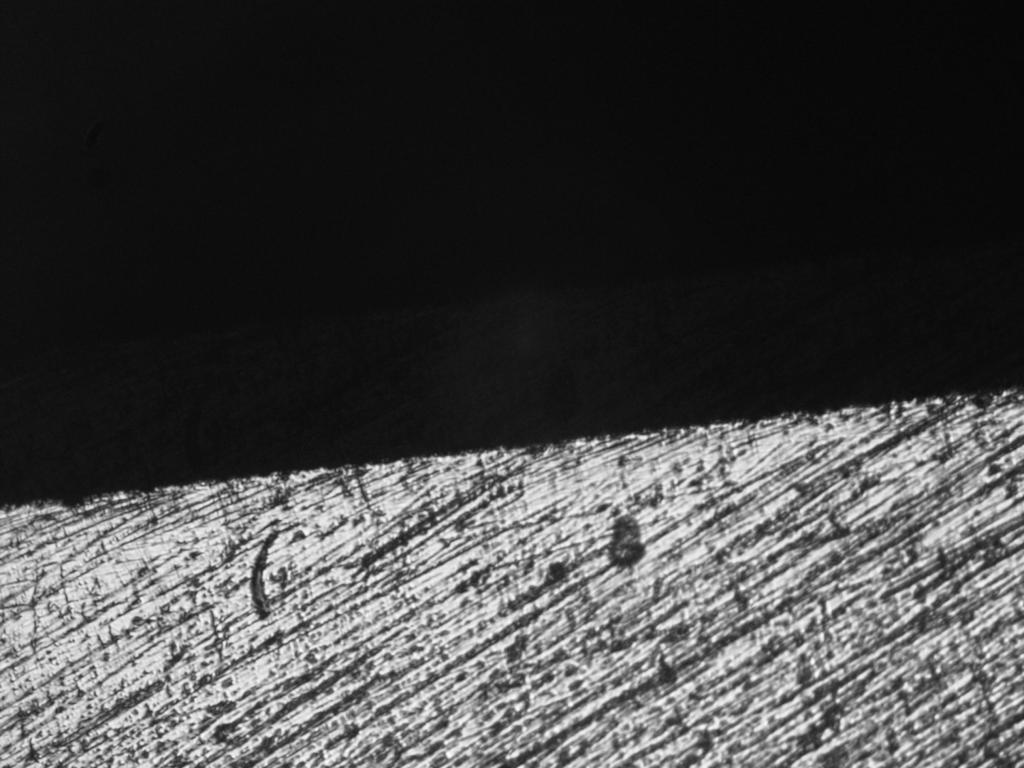

The stones don’t communicate any significant abrasion resistance or slickness, and the hardness suggests we won’t see any carbides emerging in the matrix. A picture of the matrix after planing 300 feet of cherry edge follows (and shows no significant free carbides).

The matrix shows no free carbides, suggesting the carbon content isn’t well above 0.8%. We start to see free iron carbides in steel that’s got 0.9-0.95% carbon, but not below that level.

All in all, a pleasantly good iron, but safe to say, it’s not a flawless diamond just waiting to be rehardened. That said, if you look at the edge wear (the wear picture is at twice the magnification of the original edge, so the picture’s height is less than a hundredth of an inch top to bottom), you see wonderful uniform wear. This leaves little for you to do resharpening other than remove wear. Nicking in irons generally goes about .001″ to .004″ deep (any number of nicks greater than .004″ deep makes it difficult for an iron to start a cut, thus you’ll have to do something catastrophic to see that). Minerals, silica, dirt, knots, etc, can create the typical depths mentioned. It takes a while to hone them out, and in the picture above, they would pass through the wear strip in some cases. That wear strip does not need to be honed off to refresh the iron – at least not its length. Flattening the back and honing off somewhere around .001″ of length on a completely dull iron will do the job.

Overall, nothing groundbreaking – but the iron above is a good iron and holds up its end of the bargain in sharpening vs. edge life (which is to wear uniformly in proportion to sharpening time). If I have to make a guess at carbon content, I’d say 0.8%, though I don’t think it’s 1084 – it feels as though there are a few additives – probably to make it easier to harden and temper fully. Behavior in rehardening was fine and post-heat treatment re-flattening only took a couple of minutes. Less than 5 minutes total to get to the edge shown above.

I also rehardened a block plane iron (the only iron that I may have that’s solid and between the later-make stanley and earlier laminated iron) and a “Made in USA” 750 style chisel. I’ll post those in the next several days.

A Comparison of Washita to Waterstones

It’s difficult to make a blanket statement about washita stones. I love them (the real ones – and the real ones are no longer mined and won’t come with a label like “CASE” or “SMITHS”, etc, though old enough smiths may have slipped a few in, it’s not a great bet.

A washita stone can be slurried to cut fast, it can be used with heavy pressure or it can be used with light pressure and in combination with steel hardness, you can end up with an extremely fast sharpening routine that is pretty much zero maintenance. Less than a minute for chisels and about a minute for a plane iron that’s very dull. The touch sensitivity and wide range makes it an ideal stone for an experienced user.

Over the years, I’ve had several hundred sharpening stones (probably a hundred synthetic and 300 or more natural stones). At one point, I brought in and resold (generally at cost) japanese natural stones – I just like sharpening things, but not for no reason, and I don’t like jigs or finicky things – I like methods that save time and get results.

To get on with it, I never read about using washita stones other than that a lot of people like them (and then move on to something else, but these folks are always moving on to the next thing a retailer says is great – we’re not looking for that here). It didn’t take long to find the dimension of these stones and see how fine they are. A slurried waterstone has much less dimension (synthetic types) and one of the reasons beginners like really hard irons and waterstones is they have no feel, no sharpening sense.

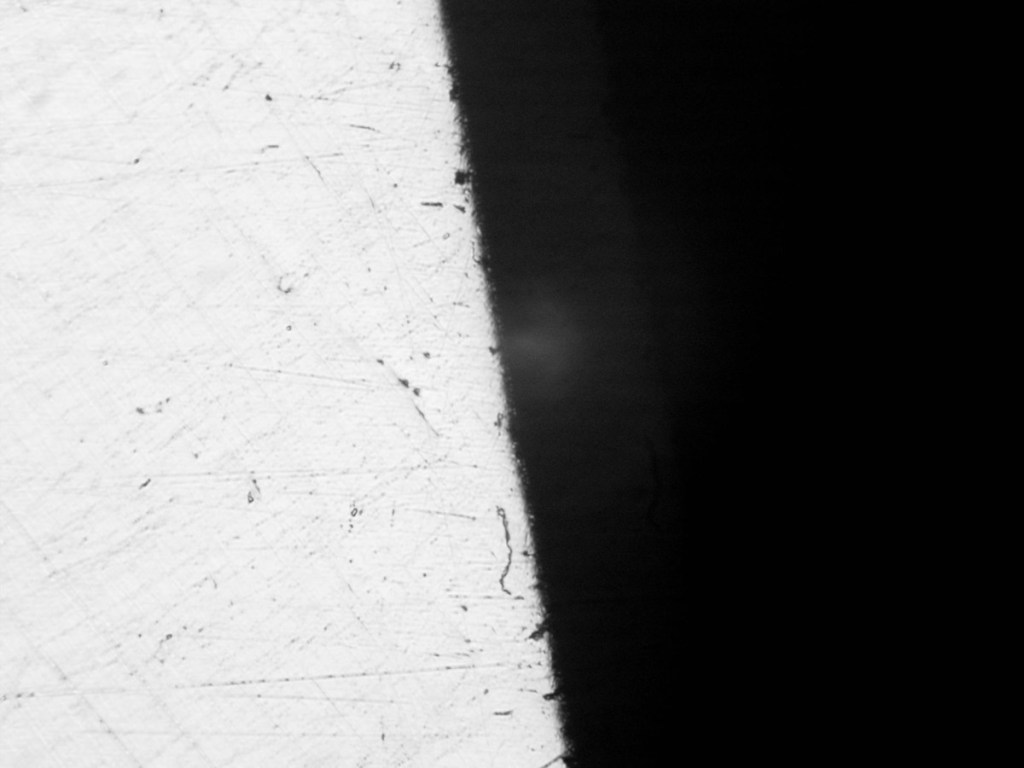

Next is a picture of an edge gotten off of an 8k grit waterstone (one marketed as “kitayama”). Notice not so much what’s on the back of the iron, but at the very edge and how straight the edge line is, and how many scratches interrupt it. You can see from the edge wear photo above that scratches on the edge don’t matter much – on a good iron, the wood just wears them off, and you’ll never see their effect – the edge itself is leaving the finished surface.

Shapton Cream (12,000 Professional):

The shapton cream is a stone that claims to be 12k, but I think particle size variation makes it more like an 8k waterstone. A quote of 1.12 or 1.2 microns is given, but many of these scratches are much larger. The variance gives speed, though – it’s otherwise a fair trade off. Again, note the torn nature of the edge.

Washita on Stanley ‘Made in USA” chisel:

First edge on the rehardened stanley chisel on a washita. Scratches don’t look much different than the stones above (which should be a surprise based on grit charts. Finishing the edge for ten second with a light touch shows an edge even-ness little different from finish waterstones, but the scratches are shallower.

Sharpening fineness vs. claimed fineness is really interesting once you get a microscope. There are stones that are closely graded and very fine (like sigma power 13k and shapton 30k), but those stones give up speed for fineness and end up being less practical in use.

A picture of a sigma power 13k edge is below – this stone claims about 0.72 microns, and does appear to be closely graded.

Sigma Power’s 13K stone does look to be closely graded, but it pays a price – it takes a long time to get this finish to the edge of a tool replacing all prior scratches unless you come from another coarser finish stone first. It’s about 1/3rd to 1/2 as fast as the shapton 12k professional, and is a bit soft and easy to gouge, so you can’t just use a really heavy hand.

If you need a fine edge following something like the washita (finer than shown), 10 seconds on MDF or hardwood with autosol yields this:

Autosol after Washita. Inexpensive, just as effective as the very fine grit sharpening stones and at least as fast (faster in this case). The polish is so bright that I should’ve turned the exposure down when taking the picture. Black spots at the edge are dirt. It’s actually pretty difficult to get all of the oil (and then clothing fibers) off of an edge to get a good clear picture.

Hi David,

First off, I’m really enjoying your posts and this format. It’s easy to follow and very interesting reading. I like the topics you’ve been covering and from the perspective of an experienced user seeking to appeal to other experienced users or those that aspire to be and aren’t satisfied with the shallow and profitable beginners information.

I had a question about the washita, I know you are a big fan and there really aren’t any other stones that match it, but since they aren’t available new and the used market can be uncertain I was wondering what other oil stone, or two used together, you would recommend to achieve the same end that can be purchased new from some place like Dan’s.

Thanks again, really enjoying following along.

Jonathan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jonathan – I think it’ll work out better in the long run as I can start linking these posts in categories and cross referencing them to avoid posting the same things at length over and over.

I noticed on WC, there’s a thread about ark stones that’s covered already by pictures I took not more than a year ago. They’re unfindable there – but would be easily found here once things are indexed.

At any rate, a decent substitute for a washita stone (if you do ever find a washita stone, I’d look for one that’s earlier and not a later branded stone or one that just says “washita oilstone” on the box without any grading)….anyway, a decent substitute is any of the following:

*” smiths hard” (older in a wooden box ). Should be a $30 stone – no reason to get it if it’s priced above that, it’s just an inexpensive soft arkansas

* “cretan” oilstone (not sure if these are still being marketed, but they were for a while – someone is mining them in greece or crete and they’re really cheap except for the fact that they get marked up a bit to get to the US – they’re a friable oilstone that’s more dense)

* “natural whetstone” also sells a “hard” that’s a lot like a smiths hard, but mine is so long ago that I couldn’t say for sure that they’re still mining the same stone (I didn’t check to make sure they’re still in business).

(I haven’t looked up washitas in a while – based on the ebay listings, looks like a tough time to buy).

I’m not a fan of Dan’s soft stones, which are relatively fine for softs (but slow cutting)

LikeLike

Thanks David. I think I get it now, it’s about a softer stone which will cut through the wear faster and then you can go straight to the buffer or something like autosol on mdf.

Jonathan

LikeLike

Yes, sort of. The deal with the washita is that it’s about the same hardness as an iron carbide – so when steel is a little softer (like a card scraper), it will cut it fast. When it’s harder, it will cut it less fast. If you press harder, it will cut faster, if you press less hard, it will cut much less fast. All of the factors sort of go together on how you want to use it.

And then the autosol is sort of the ace in your pocket (used on wood, which is a little soft and moderates its cutting) – if you want a blinding edge that’s got no or near no optically viewable scratches, then you can go there.

But the washita is sort of a stone that really rewards what you want to do with it. And a soft that’s allowed to break in will do things a lot the same, but the top level of sharpness available from a good washita seems to be missing from soft stones (the real washitas only came from one deposit/one mine – it’s a little different than all of the other novaculite).

You can also look for washitas on ebay.co.uk (there will be listings that come to the US, but it’s still expensive – I think a good 8x2x1 stone is going to end up being about $100 with shipping).

Separately, the “hard” smiths doesn’t look to be out there on ebay right now, but you can save a search and let ebay let you know when one comes up. I’ve had two smiths, I think one was $10 – things change! both were similar – relatively close in feel to a washita and nothing like a true hard (black/translucent).

LikeLike

Washitas were frequently offered from sellers in the UK before the pandemic. It’s a matter of saving a search on eBay and keeping an eye for them. Washitas branded Lily White, or with some label, are sought after by collectors and are more expensive.

Rafael

LikeLike

The unmarked stones are still over there (in the UK) in droves (more to be found if you go to the UK site and then log in there). But royal mail used to be ungodly expensive (like $30 for a box less than a kg) – it’s now far far beyond that, sometimes over $50 for a small stone less than a KG.

No clue where there are so many over there other than perhaps the fact that the trade workers didn’t give way to factory workers quite as fast. Holtzapffel’s early and late editions (one of the few things I’ve read – at least little parts of it that are about sharpening stones) show the impact of the washita – the second edition wording more or less says that the washita showed up and then dominated scene when it came to filling tool boxes.

LikeLike

There’s a lot to digest in this post, but would you care to expand on how the iron changed after re-hardening? Did it start as softer than your laminated irons? Do you think post WWII irons (presumably non-laminated according to Patrick Leach) may behave differently? I’ve a bunch of NOS Stanley irons, but I don’t know when they were made, definitely not laminated though.

Rafael

LikeLike

The type 20 iron started slightly softer than the laminated (sweetheart) iron, though not too much. Maybe a 2 points on the C scale. It is closer to its terminal usable hardness than the laminated iron was, though.

I will post the pictures of the block plane irons tomorrow – those are probably closer to the age of the laminated sweetheart irons, and they are a bit hard, but with some alloying (what’s attached to the laminated iron isn’t something stanley would’ve used in a solid iron – the T20 iron and the block plane iron were both very well behaved in quench and temper and required little follow up to get back to flat).

What I don’t know is what the earlier solid irons would’ve been – if they were oil hardening or if they were one of the W series of steels (water hardening, but the different W grades had a bunch of different alloys, and there may have been water hardening steels with tungsten in them at the time).

The block plane iron appears to have some tungsten (which supposedly fines the grain of the steel, but even in japanese blue steel, results in some dispersed large carbides – and those lead to pits in the steel when they leave).

LikeLike

I remember you wrote a few months back about cheap import chisels being alright even without rehardening. Do you have any thoughts/experience on cheap imported plane blades?

LikeLike

Not really – there are lots of different versions as they can just be stamped out and ground on a rotary grinder and be good for use. They’re often a bit soft, though – at least the ones I’ve gotten. That includes the one that used to be marketed as “buck brothers”, but those are hardened and tempered usually in a splash and I can reharden one and see what the potential is.

If someone was interested in making a decent 1% iron in china and hardening it to 62, they could just do it (their brazed high speed steel irons can be ultra hard – a couple of years ago I actually had one rockwell tested and it claimed 61 hardness but was actually 65.5 and very even hardness along the edge). However, I’ve also gotten some that are overhardened to the point that they’re worthless.

There are lots of stamped out irons on amazon and such, things in like packs of 5 for $30, but I haven’t been inclined to buy them as I literally have more than 100 irons (just not many vintage stanley). If those irons are 0.6% carbon (which is a common steel used in cheap chinese tools), they’ll be a bit of a disappointment. If they’re 1% carbon, they would make a great smoothing plane iron.

LikeLike