I made two other blog posts about rehardening stanley irons. First, a laminated iron that was very high carbon water hardening steel and rehardened to a very high level (but stability is an issue). And then yesterday, a type 20 iron that doesn’t have the same potential, but did turn out to be a nicer iron for the bench after rehardening and by no means low quality steel or too soft. Just a more modern lower carbon fine grained steel that doesn’t show anything that threatens uniformity. That post is here:

examining-a-later-stanley-iron-rehardened-how-bad-not-as-bad-as-the-reputation

Referencing that relieves some of the need to repeat a lot of the details.

The third iron in this case is a replacement iron for a stanley 18 (it probably fits other planes, but I don’t use block planes much). I’ve since lost the box that a group of these came in, but they’re a little soft. Enough so that a beginner comparing them to a boutique plane would probably complain, but the steel is uniform. Buffing the cutting edge (they’re bevel up, so no concern about clearance) eliminates any edge holding issues they’d have due to softness, and you can then use them stock to plane anything. Your hands will hurt before they’re dull (anything includes cocobolo with silica or bubinga, something you’re not likely to read on forums or in ad copy – I’ll save geometry at the edge for another time. Safe to say, you can plane anything with an iron like this until your hands are sore if you modify just the very tip of the iron (not even enough to make it feel dull).

At any rate, a picture of the iron (it’s filthy from being rehardened – when you buy a new iron, the iron is ground post heat-treat all of the hardening and tempering colors are erased).

I’ll leave guessing the age to the tool collectors.

Rehardening Results

This iron is solid, and it’s a different steel than the type 20 stanley iron and definitely not the same water hardening steel that’s laminated in on the sweetheart iron.

Hardness is also between the two. It cuts freely, but not fast, on the india stone and cuts little on the back side on the washita and lets go of its wire edge pretty easily. Hardness is probably a point harder (maybe two is more likely) than the type 20 bench plane iron after rehardening and a point softer than the laminated iron after rehardening (same 400F double temper, same hardening process). (Adding as an edit – a second session trying this iron with some stones shows that the washita is struggling in a fair fight with this one – it’s fairly hard. Any harder, and it may be impractical for use with the washita stone).

Behavior in the quench was good (as in, it’s entirely reasonable to reharden these if you can swallow the cost of setting up a small forge and buying fast oil to get full hardness). You can temper in your kitchen oven if you use a thermometer to find an area where temperature is steady.

The feel is different – more like water hardening steel (the feel on the stones that is), and less like oil hardening, but it’s difficult to know for sure without having XRF analysis done to tell the composition – that’s not something I have easy access too. The carbides might tell us something.

The finished iron (without any type of stropping at all) after teasing off the bulk of the wire edge is here (straight off of the washita). The buffer does a nice job of making the edge very straight after this, but it would plane fine with this tiny burr left on the iron.

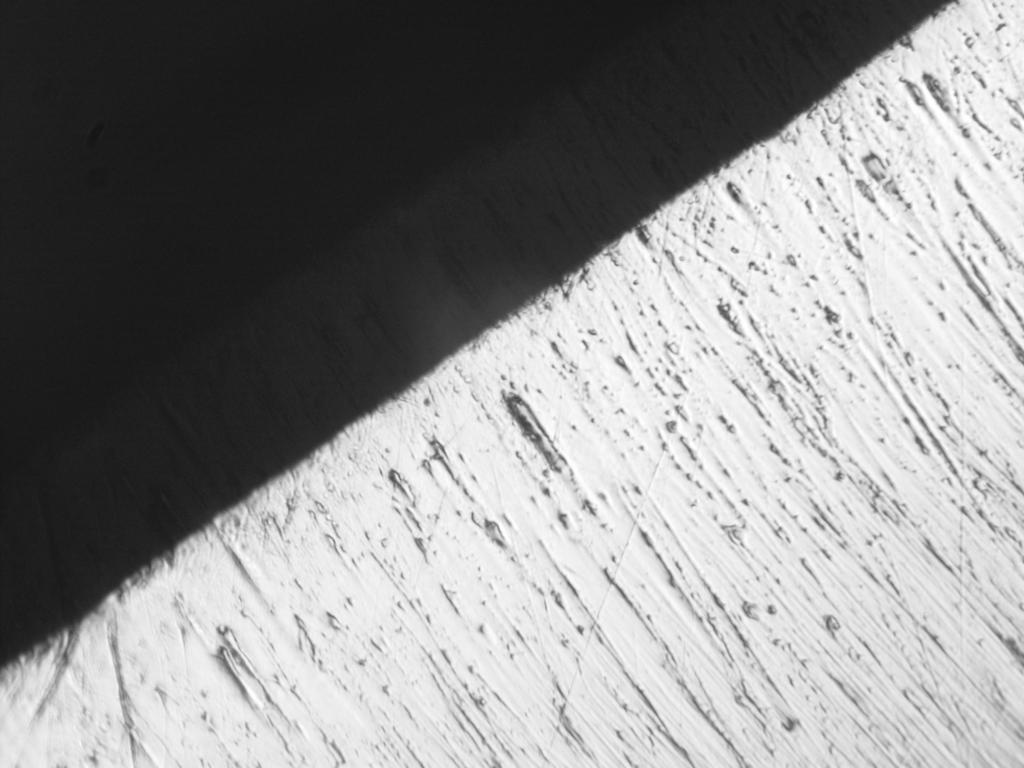

Picture of the Carbides

So, as I’d suspect from the feel and the hardness, there’s a little more of something here than there was in the perfectly uniform later iron in yesterday’s post. It’s not as subtle and even as iron carbides in 1095, which makes me wonder if there is some tungsten in the iron. That wondering will have to live on (but the comment is based on the fact that tungsten in quantity will make the odd large carbide here or there, and they’re not consistent in size).

I can make the statement, though, that this is a very good iron, and again like the laminated iron, stanley left it softer by choice. This iron has (and shows by results) a little more potential in rehardening than the later irons, though by feel on the stones, there’s nothing in it that would make it highly wear resistant for boutique edge chasers. It’s just honest, wears very evenly, lets go of its burr in sharpening without any effort and is quick and very practical without being soft.

I don’t know Stanley’s motivation for making irons softer than they needed to be based on the compositions they chose, but that speculation is in prior posts to some extent, but it may also be a case of steels like this being more forgiving to fast or cheaper processes. There’s nothing difficult about my hardening routine, but it does take a little bit of time. I think for practical purposes, just making the iron really hot and requenching it would be 90% as good, and still nicer for a bench user vs. a site user (carpenter). Carpenters were probably the target market, anyway – quick here and there use. Planing any significant amount of time with a block plane is a good way to know why you don’t want to use them for serious work.

(would I honestly tell you that I’d pick this iron over a replacement V11 or A2 iron as a matter of both use and productivity? Definitely. I think if you stray from those alloys or something from hock and get into lower cost sources of irons, you chance ending up with an iron that’s not much harder – or any harder – than the original. I would choose this iron over a boutique iron because it’s far nicer to sharpen and grind and the difference in edge life of a boutique iron wouldn’t be proportional to the additional sharpening time. This equation may be different for a beginner who sharpens everything the same way with a guide).