Coticules are a relatively popular finishing stone from the Ardennes region in Belgium. Historically, they’ve been more popular as a multi-use stone in continental Europe (finishing tools, razors, knives, etc), but most of the references that I see in catalogs in the US are for branded razor hones. That is, those sold here before hobbyists became the main buyers of everything were sold as fine graded razor hones, often fairly small. Pike and Carborundum come to mind – I’m not a huge collector of them and only have a couple, so the list of US distributors branding coticule razor hones is probably pretty long.

The advent of shaving forums brought interest back for these stones. They’re overpriced for what they are in my opinion, but so is just about everything used for shaving. Despite the nostalgic mention here and there of someone recalling a Dutch woodworker they knew, I’d also put coticules at the bottom of any list of natural stones to try for woodworking. At one point, there were at least 7 different mines bringing out coticule material, and generally at the seam where the cream colored abrasive meets a blue stone layer. The blue stone also hones, but it’s generally not present on modern-mined hones. The tell for a stone you’re looking at is whether or not you can see a layer of glue, even if the dark backing is scuffed or dusty and not discernible. The natural blue stone when wet and smooth often has a bluish or purplish tone and markings that look like peacock feathers.

There are also glued stones older in age with a blue stone (abrasive natural) backing instead of slate. The reason the stones are cut at the seam is probably two-fold, but at least one is that the yellow abrasive layer by itself is unstable and can crack, and age isn’t a guarantee that the stone won’t crack as I had a natural combination “Old Rock” labeled that hadn’t been used, and over the 6 or 8 years I had it, visible cracks started to form. Cracking makes the stones harder to resell.

To my knowledge, only Ardennes is mining and cutting coticule hones, and the stones vary a lot in cutting speed, feel and fineness. A relatively small glued hone is generally about $100, and the sky is the limit above that. Anyone buying an 8×3 glued stone for $400 or more will be disappointed unless their objective is to use a coticule no matter what. Unless there is a secret somewhere, the typical customer for an ardennes hone is a straight razor user.

That said, it’s possible to get one that is very good and that creates a comfortable shaving razor, and it’s also the case that an experienced shaver is rarely going to hone (the linen and leather will stretch an edge for a year without much degradation – a good linen and leather, that is – and an experienced shaver will not do much honing, and certainly not the heavy handed honing we do for woodworking tools to remove wear. A properly maintained razor doesn’t wear much and the honing just keeps the bevel and apex from getting fat).

The abrasive in coticules is apparently garnet or something similar, and the abrasive is sort of tubby and round as opposed to disc shaped or more pointed like alumina will often be. That means that you can’t judge much by particle size (coticule abrasive particles are generally fairly large and not the more typical 3 microns or so that most fine natural abrasives land near).

Long story short, if you go out and buy 10 coticules hoping for 8 wonderful users, you’ve been warned. If you buy large older stones, there’s a fair chance you’ll get sandstone that looks like coticule, or a hard coarse actual coticule that was never intended for finishing (these are no longer marketed).

Typical use honing with a coticule is like a slurried arkansas stone. With slurry, the stones will be faster, but there will be something referred to as slurry dulling (the rolling particles will round the edge somewhat and leave it a little bit uneven).

While I’ve probably had more than 10 coticules, I have two right now, and that brings to mind a third very thin yellow layer stone, so I guess that makes three (thin yellow layer meaning someone used most of the preferred yellow side – it’s an older stone with a blue stone backing, and only a very very thin layer is left – it was cheap).

Of the large group of stones, I had one natural combination stone that was large and that did a nice job polishing an edge and had good cutting power. Every single stone I’ve had is markedly different in feel and speed, though. That stone was expensive and when I leveled with myself about it not really being better than any other typical stone (for example, a black arkansas still results in a sharper razor), I resold it fearing the fad would go away if the razor forums lost traffic.

I’ve kept one bout #10 (an odd shaped stone about double the area of a deck of playing cards) and then a really fine slow coticule that hardly cuts. The pictures below are from these two.

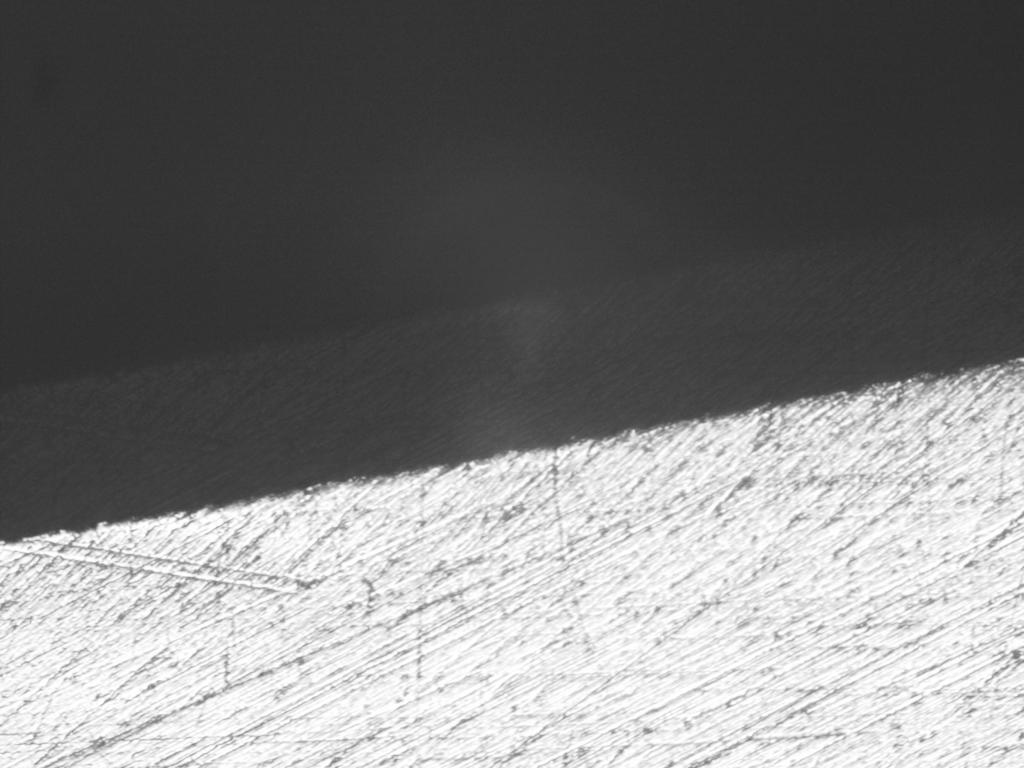

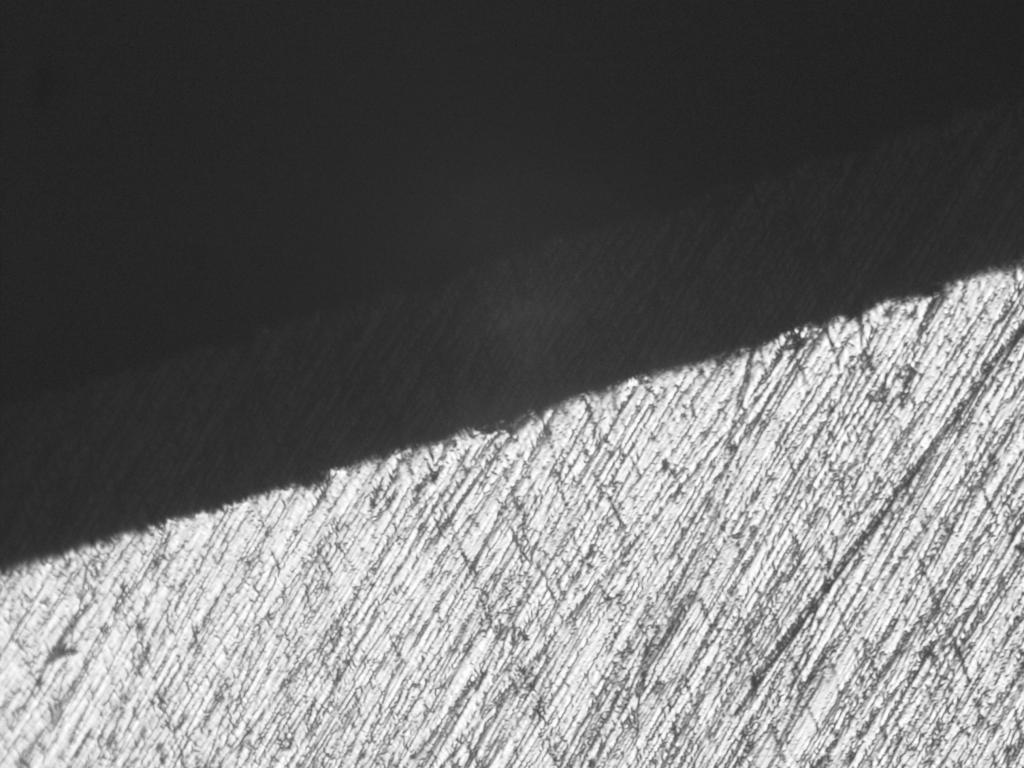

Compare this Picture to the 8,000 Grit Waterstone

First, the coarse coticule

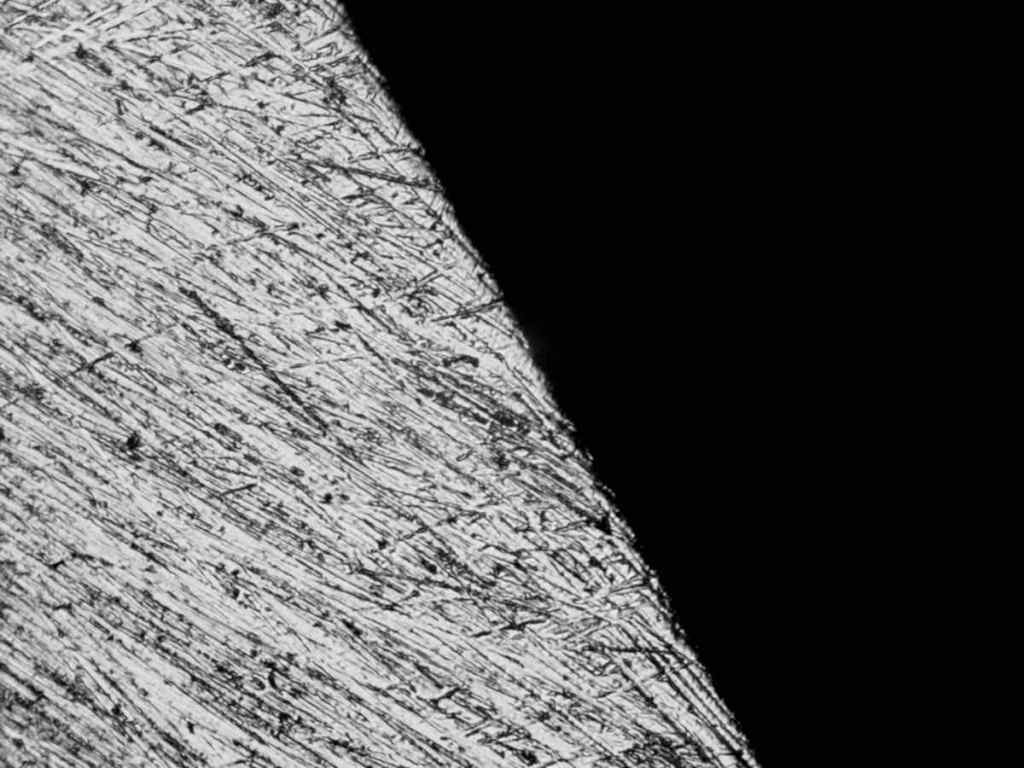

And the edge of the same iron off of the finer of the two

At this point, there may be a person or two who mostly shaves or maybe someone who uses coticules as a finisher for woodworking. As with all stones, of course, you can use them for woodworking, and of course they’re suitable for straight razors. Part of the interest in sharpening stones is all of them work. If I chanced across a large coticule at a flea market for a reasonable price, I’d probably buy it and plan to just unload it when the thrill wore off. The lukewarm thoughts about this type of stone aren’t whether or not it can be made to work just fine, but rather whether or not it makes sense when there are better options that cost less.

Looking elsewhere will also save you from the strange fascination with giving different layers names, much like the “in the club” kind of thing with japanese natural stones where the true users of the stones don’t care that much what the name of the stone is, they care how it feels and works. If you are on a woodworking forum or a shaving forum, someone extremely enthusiastic about arbitrary titles will be correcting you when you’re trying to convey from a sense of doing. They’ll tell you that “you have to learn what you’re talking about” with the various layers and labels before you can talk about your own stones or ask questions – you can ignore that stuff.

The one thing these stones do have in their favor, especially if you manage to find an older natural combination with a label on – and you manage to luck into such a thing where it’s being sold for a song. They’re pretty, both the yellow layer and the natural blue layer when the blue has a lot of birdseye-ish pattern.