Half the price of O1 and at least as good in plane irons. I put off even considering this alloy for chisels because the data sheet shows it being around 60 hardness at a 400F temper. I find favor with most 1% and higher steels around 400F, but admit that I don’t have a great reason to believe that it’s the best temperature for everything.

The other thing against 80CrV2 is that it’s a not an expensive steel but it’s not as cheap as it could be with some retailers, and the prices is around what you’d expect for O1. While making an order a couple of weeks ago, I found that NJ Steel Baron doesn’t charge too much more than the very lowest cost HC steels like 1084 and 1095.

So, what is it? I’ve never heard of it as a woodworker, but saw someone else attribute a statement to Larrin Thomas that it is used in woodworking tools. If you’re purchasing LN, LV or other boutique tools, it’s probably not going to be there. Maybe it’s used in carving tools and plane irons in europe, or maybe it’s used in what are lower class chisels for woodworking, but the top of the range hardware store chisels in the $15-$20 each. I really don’t know.

From 1084 and 1095, the Troubles

1084 and 1095 gave me trouble until I snapped samples to see what color and time they will show before grain growth is a problem. 1095 isn’t too bad, but 1084 is a different story. Shoot a little too high before the quench and grain growth doubles. Do that while thermal cycling and the point of cycling gets lost, plus the quench. You have to be attendant with it, and give it only a few seconds if chasing the quench temperature up and not nearly as high as something like 26c3 will tolerate. Put differently, the routine that I used to better any published results for 26c3 results in *very* poor 1084.

I’d hoped to find 1095-ish with chromium and vanadium. The former to add some toughness without sacrificing hardenability, and the latter to pin grain size, allow for the overshot that I like to ensure hardness. It’s not to be, and 52100 just isn’t very good for woodworking.

1084 also will not ever wear as long as O1, but it does OK. that isn’t a problem with chisels, and the toughness of 1084 was good enough once I solved not growing grain that it will make a fine plane iron tempered a little lower. Translation – it can be as hard as O1 and 1095 will tolerate planing.

Seeing the better than expected corrected version of 1084, I made a couple of plane irons out of 80crV2 and used an offcut that was waste off of the same sheet and snapped samples. The grain is as fine as anything I’ve ever seen that attains high hardness, and the hardness was a little better than I expected starting with a 375F double temper. I suspect it’s around 61/62, about the same as O1 tempered at 400F.

I’m going to avoid going into a broad discussion about how much carbon is in solution (not in carbides) in each of the steels, but for brevity, some steels suffer from too much of it remaining in the lattice and not in carbides. The resulting toughness vs. pictures of the snapped grain or micrographs can seemingly be 1/3 of expected. This isn’t always bad – o1 is far less tough than 52100, but it’s nicer to use.

What is it?

Despite the dreaded “chrome vanadium” name, it is not some soft shiny steel that makes a terrible chisel. That label given to the variety is ill attributed because someone knew the combination of favorable properties – limiting grain growth and toughness, but paired them with a low carbon amount – often 0.5 or 0.6% carbon. This isn’t really much good for woodworking, and the 0.6% variety is listed a lot in not-quite-hard-enough-chisels from China. When I reharden them, they are only a little better – there’s just not much potential.

80CrV2 is 0.8 or 0.85% carbon, manganese of about 0.4% (just over half of 1084), Chromium taking place of some of the manganese (0.5%) and a small amount of vanadium (0.2%). It’s a water hardening steel, so we’re not likely to see any of the boutique US makers making it. The chromium and vanadium are enough to make it more friendly to heat treat than the plainest of steels, but they won’t make it feel gummy or slick like A2, etc.

In woodworking, you will often see O1 labeled as plain carbon steel, but if you work with older tools or 1095 or 26c3 or whatever else of that sort, you’ll notice the feel of the alloying in O1. it’s not bad, but you can feel it. it’s more obvious in 52100 due to the chromium content (1.5%), and, of course, once you get used to plain steels, A2 feels terrible. V11 also gets its slickness for a huge dose of chromium.

I can’t well compare grain size from snapped samples with 80CrV2 to anything else I have because I had to double the magnification on my hand scope to 100x optical to see any difference in samples just heated from bar and quenched, then thermal cycled and then the same as the latter but with an intentional simulated careless overheat.

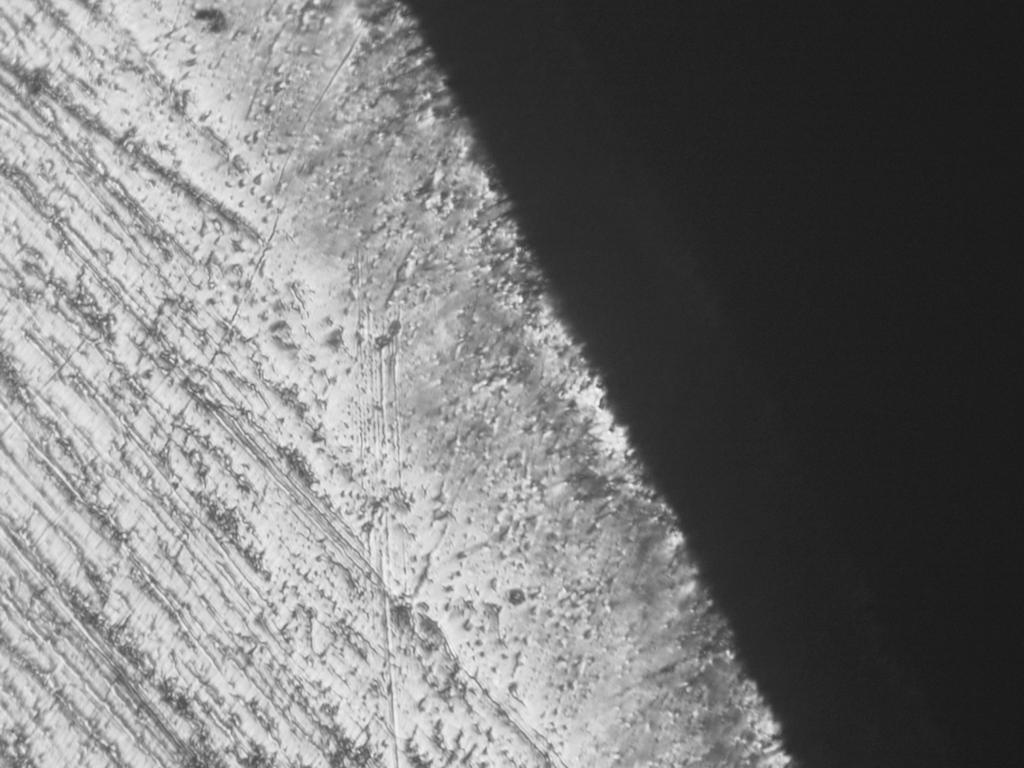

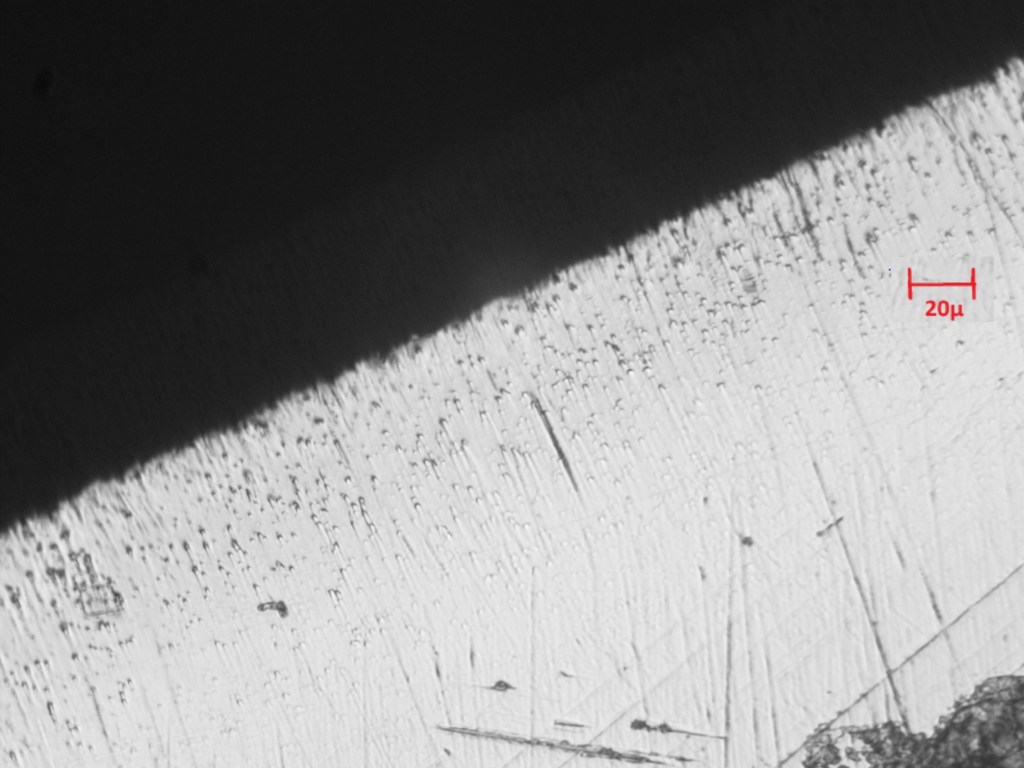

Here’s the snapped sample from the quick heat at 100x:

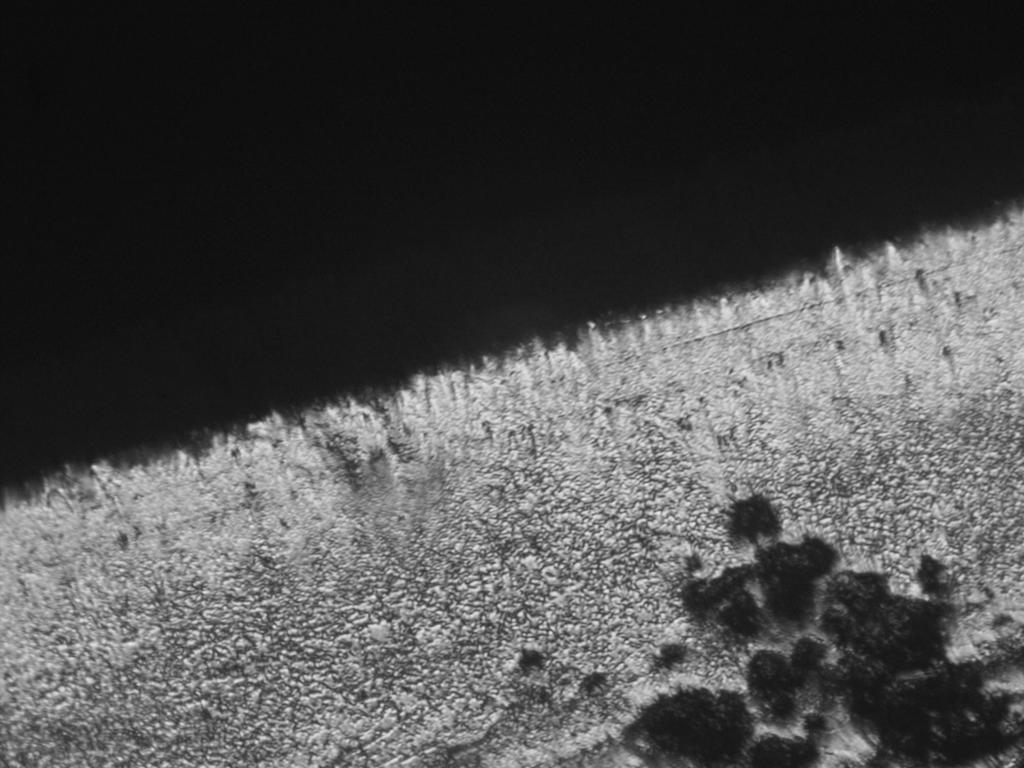

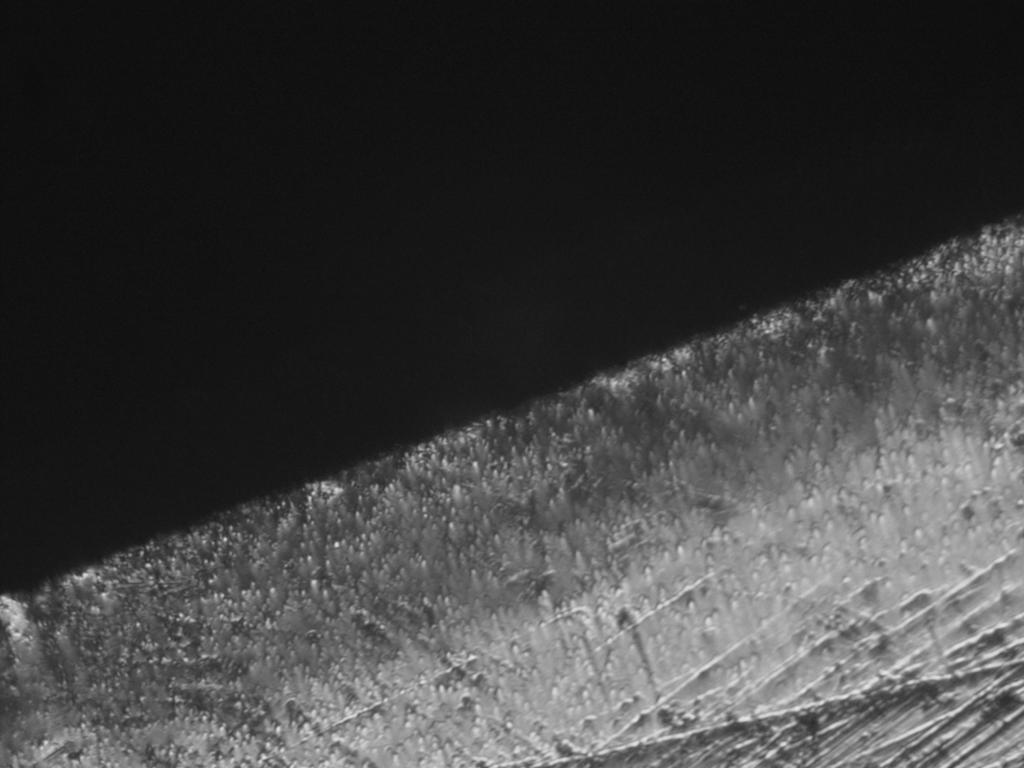

Next, the same magnification but with three thermal cycles.

that’s outstanding. Even looking at this under a loupe you can’t see much.

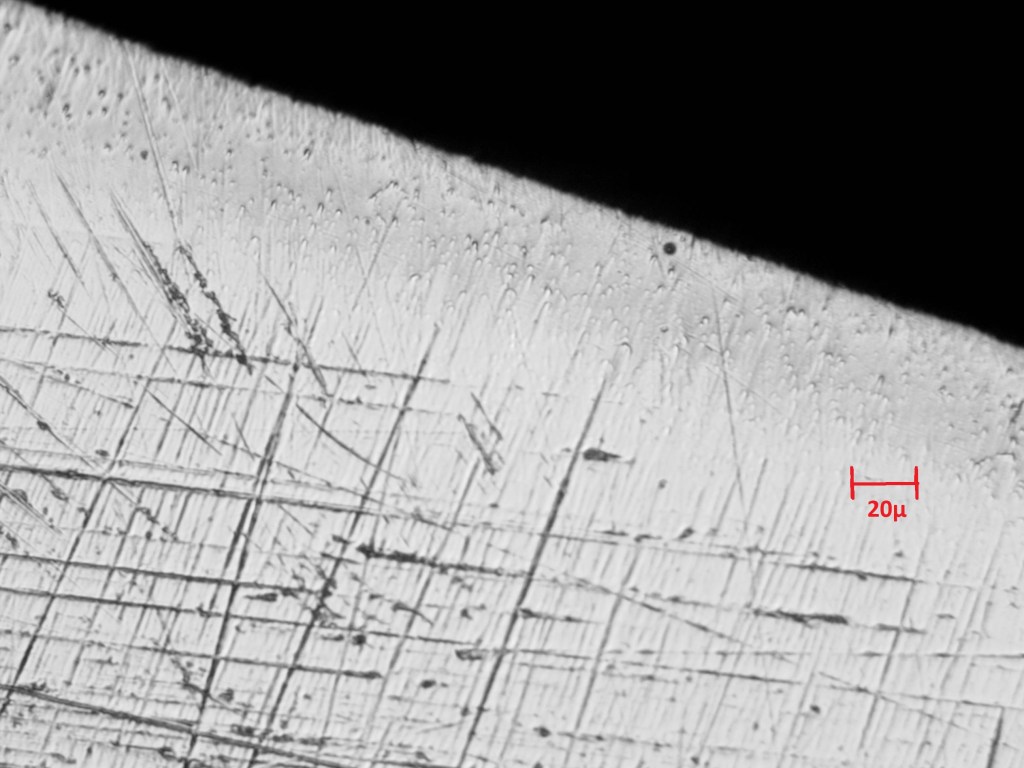

Here’s the kicker – doing the same thing as above but allowing the sample to overshoot in 15 seconds to a very bright orange resulted in….wait for it.

Nothing. This is not a long duration forge heat, so it’s not license to just disregard what temperature does to steel. This would be more like what a beginner may unintentionally do. It may look at first sight like the second picture shows larger grain than the third, but I think that the actual sample had a little more toughness breaking and if you look at the individual grains, you’ll find them similar in size – especially given the limitations of snapped samples being photographed with a microscope that I got for $12.

1084 steel is constantly recommended to beginners. I think they have no chance if they’re using a forge. This is what beginners should be starting with. But the forgiveness allows more advanced forge heat treaters to get otherworldly consistent results without being as taxing as 1084.

There is toughness in reserve with this steel, so it would probably hold up in a plane iron tempered hard (like 63/64). Hard tempered irons are OK, I guess, but I generally like something around a hardness that the washita likes – somewhere around 62. More hardness means slower sharpening and the sharpening effort seems to increase faster than any footage gained planing.

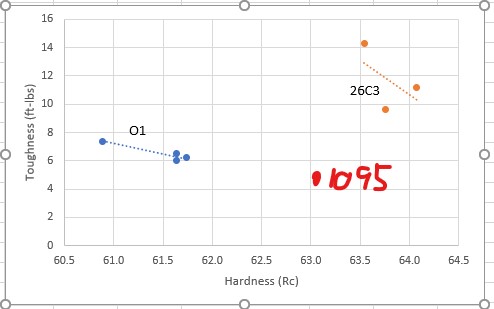

So, How Long Does it Wear?

About the same as O1 – which is nice, because 1095 and 1084 don’t last that long, and neither does an old Ward iron or an iron made of 26c3.

To test this, I planed a single board alternating with an O1 iron that I already have and one of the new 80Crv2 irons, and I took pictures of the carbides about 2/3rds of the way through. I want to see how long each planes, but discern difference in how the edges feel because there’s a fair chance I may start using this stuff in my own plane irons.

The bottom line is at similar hardness, the edge life was almost identical. On the cherry board with a chosen shaving thickness, I planed 783 feet with 80CrV2 and 778 with O1. When clearance runs out, it lets you know ahead of time, but when it tips over toward not allow the plane to pick up a shaving, it seems to happen all at once. the margin of error in this test is probably 25 feet of planing, so figure these are about the same. that’s all I need to know.

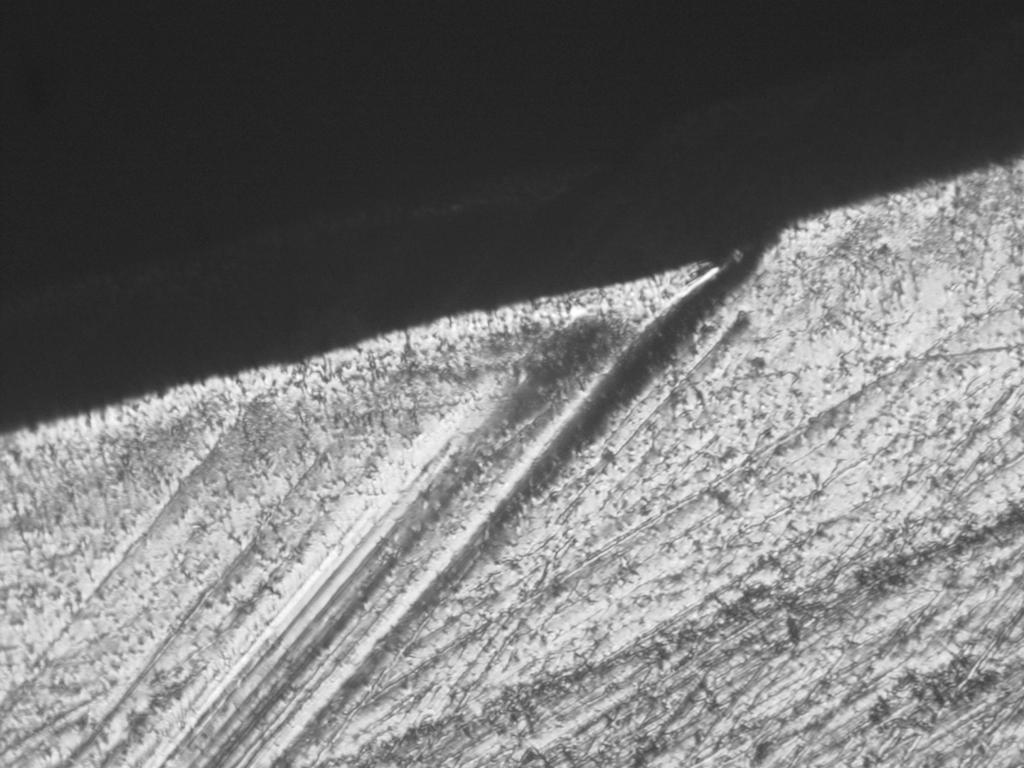

Pictures of the carbides – O1 first, and since there was a lot of heavy edge wear, I had to turn up the light on the microscope. What I’m looking for is a nice even edge, and even carbides.

In the 52100 post, I showed O1 with much less wear. This is Bohler O1 and I think the others was starrett. But the real difference is far more war, exposing more shadowing with carbides in the worn edge. That is, some part of them is pointed directly back at the lens wheras the edge is rounded and appears dark because it reflects light elsewhere. there are a few odd carbides here or there, but these are seemingly 2 or 3 microns. Maybe they’re tungsten.

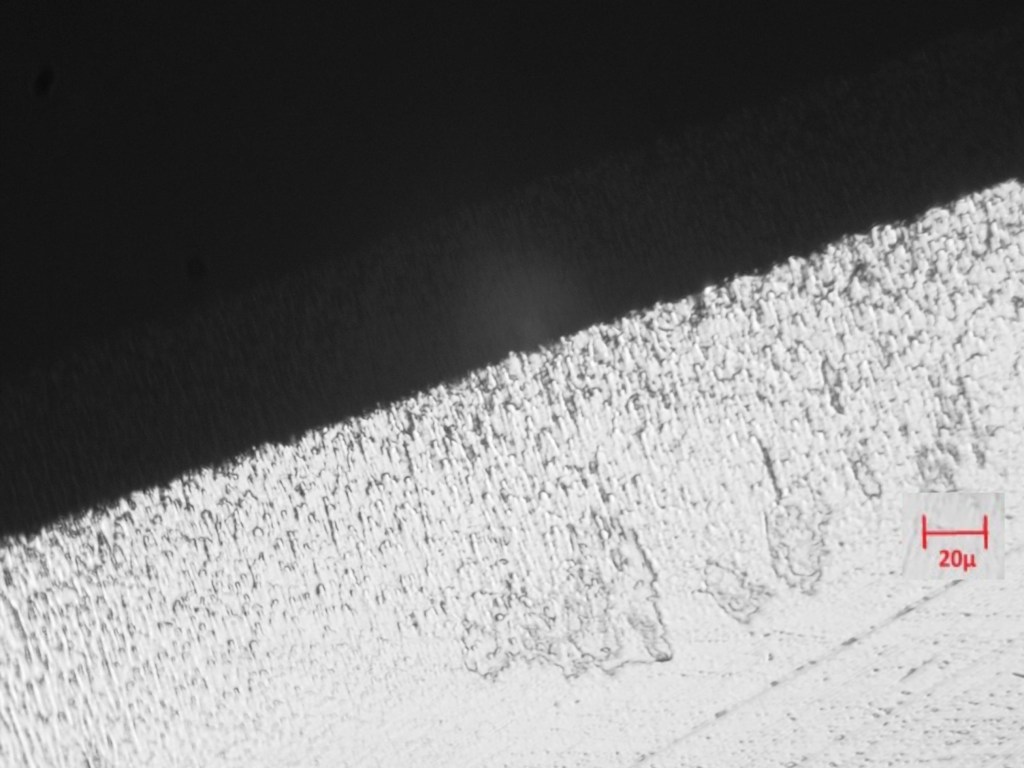

Now, the 80CrV2:

These are extremely high magnification (300x optical – the height of the picture is less than 1/100th of an inch in reality), but look at the tiny evenly dispersed carbides. The slightly different shape in the wear – who knows, it could be just how the steel wears or slight differences in cap iron setting. nonetheless, anywhere you see anything that looks like it’s even 2 microns, it’s probably two carbides close together.

it felt just a little sweeter. The evenness of the edge probably shows why.

So, what are we looking at in costs? A sheet of steel that will make 6 stanley plane irons costs $32.50 as I type this. There’s enough left for half a dozen marking knives or several nice kitchen paring knives. After allocating shipping to this sheet, we’re in the ballpark of $6-$7 an iron. bumping up to Lie-Nielsen or Infill thickness irons and the cost goes up a little bit, but I’d consider making a few LN replacement irons as there is no alternative to dumpy A2 now. I don’t have LN planes any longer, but I do have spokeshaves, and the A2 blades for them are just a terrible choice.

What about Chisels?

26c3 is probably unbeatable – it sharpens easily, it attains really high hardness easily and the crispness of the edge is superb. It’s not nearly as widely available, either.

But I will probably make a few 80CrV2 chisels just to see what they feel like at 350F temper and then down from there (or up in temperature and down in hardness). I think 26c3 is easy to get right, but a beginner may not have much chance of doing that in a forge, and my test samples bettered published specs, so I would be hesitant to guess how good it is in a furnace. The knifesteelnerds suggested heat treatment doesn’t get results that I get, and I think that’s a shame, but the steel itself may also not have that much value to knife users who can be wooed with the promise of something better that isn’t functionally better.

And in all fairness, though I have not a single positive thing to say about Devin Thomas, Larrin is the one who in his characteristic brevity when I asked about a 1% CrV steel, suggested 80CrV2, and maybe seeing the suggestion the 15th time tipped me from feeling like I didn’t need to short carbon well below 1% because I have the skill to work with steels more difficult ….to trying it anyway.

Would We Ever See it in Boutique Tools?

I doubt it. There are some things that I do to chase hardness that require hands on skill and some experience. I’ve now probably heat treated at least 300 items and I have not just heat treated them, but I have been using it as a fun exercise to try to get better and more consistent. I’ve also never had to do it on a Tuesday afternoon with a hangover or organize 50 items at a time. If I harden and temper 10 items in a busy week, that’s a lot, and I usually limit what I’m doing to cycling two items at a time. I’m kind of dumb, and trying to keep track of more than two things that are changing colors and in and out of the forge is a good way to make a mistake.