There’s a rumor that the market included plain steels in tools along with the idea that synthetic sharpening stones are also a new thing. Neither is true, but it is the case that prior attempts at tarting up woodworking hand tools with high speed steel (HSS), or razors with significant amounts of tungsten in them were relatively unpopular.

A lot of synthetic stones were marketed in the late 1800s and early 1900s at high cost and also were hit or miss.

High speed steel goes back at least as far as Mushet steel. Think O-1 steel, which is easier to harden thanks to a big dose of manganese, but with much more manganese to the point that if you overheat the steel, it rehardens just with exposure to air. Hardenability is a term that’s used to describe how slowly a steel can cool and still reharden, and “hot hardness” is a term to describe how well it performs when it’s hot. Air hardening high speed steels are both highly hardenable and with good hot hardness. Others, like A2, are air hardening “high hardenability” steels that don’t fare well once they’re exposed to heat.

Mushet was an early (first?) example, but the steel was brittle and what we will find in woodworking tools is more likely to be earlier tungsten alloys followed by the more common M-series, where M2 took over thanks in large part to being lower cost than tungsten high speed steels.

Mountford’s Revilo HSS Iron

Mountford was apparently a scythe or farm tool manufacturer, and at some point in the late 1800s or probably more likely, early 1900s, they marketed a high speed steel parallel iron for infill planes. You see them from time to time, but they’re not as common as Ward and Payne, for example. If I had to guess about the age of the one that I have by the font and style, I’d guess 1925-1930. An iron like this is something I might buy out of curiosity, but in this case, I bought a plane that already had the iron below as a replacement iron.

What I found interesting before getting this iron is that sometimes I would see listings for planes with a Revilo HSS type iron that was well used. Some even to the slot. When you see this, that usually means the iron was sharpenable and pleasant to use.

We get confused now with boutique offerings that are high hardness and one of the myths of HSS is that it’s always really hard. I looked up an M-2 alloy hardening and tempering schedule and it provided instructions for tempered hardness from 56 to 66 on the rockwell c scale. For someone sharpening on stones, this makes for a huge variation in what you perceive, and most amateurs wouldn’t think two irons at the extreme ends – or even middle and one end – were the same steel.

Where does his hardness myth come from? I guess it must make some kind of sense that a steel that does well cutting other steels would be really hard, but the high speed reference is related to the fact that the alloy can be used for “hot work”. Allowing work to be cut and shaped at higher speed means higher volume, more efficiency. The steel doesn’t have to be hard to do this hot work – it just needs to retain its hardness well past temperatures where cold work steels will become soft.

Moving on to the idea of consumed high speed steel older irons – I suspected that the Mountford/Revilo irons were tempered a bit soft so that they could be sharpened on typical sharpening stones, and that’s the case. Most older tools that are overhard without later correction just go unused, and the listings that I’ve found of these half or mostly consumed tips us off. I can sharpen this particular iron easily with an india stone and washita stone as a finisher.

What is the composition? I have no idea, but an XRF analysis would figure it out pretty quickly. At its early age, the hard steel lamination on the iron could be a T-series high speed steel. It looks like Mountford was in business at least until just prior to WWII, but since plane irons weren’t their main business, there’s no reason to conclude they were making these from introduction to closing business. If I ever have the chance to get XRF analysis done on a group of irons, I’ll try to remember to include this one.

What is it like to use the Iron?

Since it’s tempered fairly soft, it’s hard to tell that it’s high speed steel. If it wasn’t marked, I wouldn’t know either, until grinding it and seeing that it probably wouldn’t spark like a typical older iron. I haven’t ground the bevel on this one in a while, though, and don’t remember if that’s the case. But you can just use it like you would anything else without special grinding or sharpening considerations.

Why didn’t they ever catch on? Unless you want to heat the iron on a grinder, high speed steels in hand tools and things of the like offer no real improvement for professionals. The cost was probably also higher than typical irons, but one would have to find a listing to prove that. I have used this particular iron occasionally and would speculate that the edge life is similar to a good carbon steel iron, but to get a picture of the carbides, I paid a little bit more attention. It seems to lose sharpness and the ability to keep the plane easily at a point and fairly quickly. That is, it planes well for a while, and when it starts to fall over in sharpness, it does so quickly.

This is back to cork sniffing talk again, but I have this same experience with 52100. The edge seems to wear more in a rounded shape and less crisply and if you just keep pushing it, it’ll cut for a while, but it feels less nice to use than O-1. This iron has that, too. I think it would fare fine if it was higher hardness and hold a more “pointy” apex as it wears, but that’s just speculating and at higher hardness, craftsmen would also have liked it little. Could it be that the ability to grind it briskly with a wheel grinder was the selling point? Maybe.

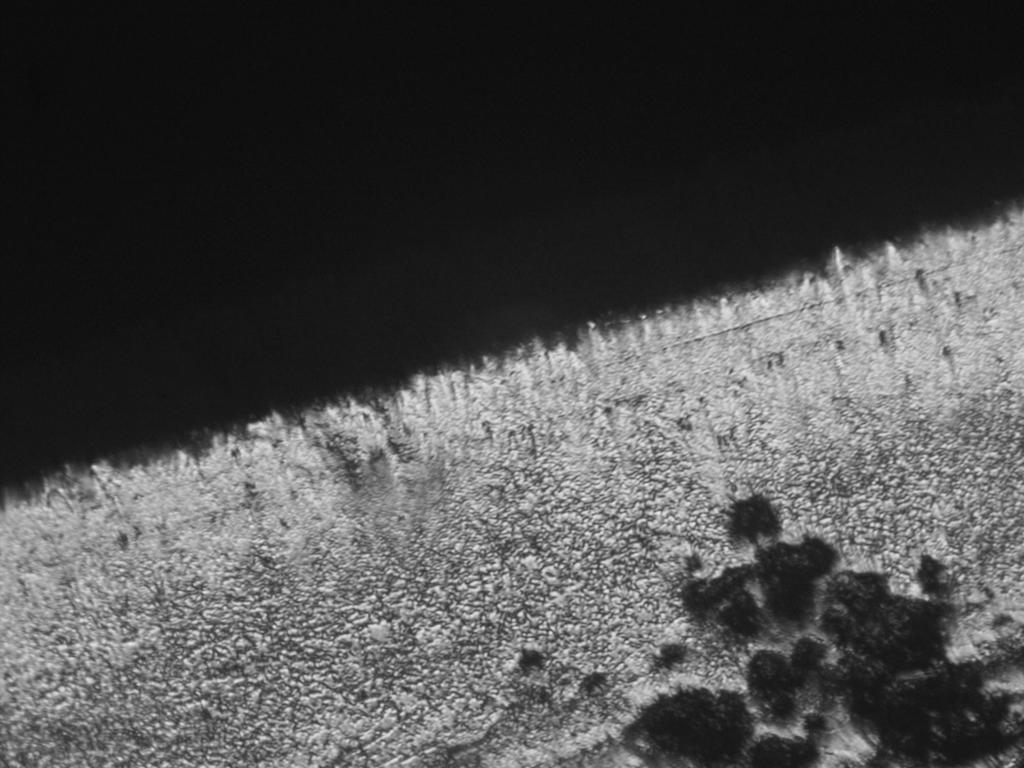

A picture of the carbide pattern and the worn edge is below to illustrate what I found. In short, it does wear a little bit unevenly, and I think the lattice between the carbides lacks hardness a little bit. This is after several hundred feet of planing, though, so it doesn’t just fall on its face. Interestingly, since I work the back with a washita, it retains a haze instead of a polish and often under the microscope, you can find out why. In this case, it looks like the washita hones the lattice but some of the carbides remain in place. They don’t look large. which is good, but the edge still looks kind of ragged.

You can compare the uniformity of the worn edge with yesterday’s darling – the very plain “cold work” 50-100 alloy (1% carbon, 0.6% chromium, and some manganese plus only little bits of anything else).

Sharon Steel Worn Edge / Carbides Picture

I’d rather have a good quality traditional iron if a solid conclusion is desired. I think the market decided the same thing. Around this time or not long after, though, Norris went to R. Sorby irons, which are also soft and disappointing in the planes where they appear, so I don’t know if a crisp new Ward iron was still a possibility.