I’ve been making blades out of sharon 50-100 all week – one a day as it’s something I can do in less than an hour, and the ability to use a plane and then examine the edge under a microscope to see what I have is just about the ultimate initial test. If the iron is good, it will sharpen easily and well and wear evenly without chipping and folding.

If it passes that, then it’s time to use it rougher wood. The dilemma in this case is that it’s an antiquated steel by now and the found lot is 0.145″ thick. So, I can make infill irons with it and maybe large moulding irons.

Making a plane iron in a shop without machine tools and then quenching and tempering – especially a water hardening steel that’s just mill finish to begin with – means flattening an iron and getting an initial edge. I consider the entire establishing of the bevel, flattening the back and honing both to be a 10 minute job. I’ve been doing this for a while and have gotten good at all of the steps. That reminds me, I have an improved back flattening jig to share, but I’ll post about that separately.

Forums and Assigning Fault

When you read forums, you’ll hear all kinds of suppositions. Any time someone talks about a commercial iron being chippy or microchippy, or whatever else, I always challenge them to get a hand held microscope and view the edge of the iron before they start planing. A2 is relatively notorious because Lie Nielsen recommends hand grinding it and it’s more resistant to stones than most simpler steels. If someone even manages to properly finish an edge, they’re faced with nicking an iron, perhaps, and having to hand grind out the nicking.

They have practically no chance.

Hand grinding a small nick or small nicks out of an iron means honing off several thousandths of edge length, perhaps 4 or 5 at the most if there isn’t catastrophic damage, and the idea that you’ll do this in the middle of working on something is a no-go. Most of us have calipers – I’d estimate that a brisk sharpening session on a secondary bevel takes about 1 thousandth of length off of an iron.

My point is that what you see occurring is easy to attribute to “microchippiness” of A2. This is often the accusation. However, I fully honed, examined and planed a couple of thousand feet with A2 irons and found no evidence of chipping. The edge can get ever so slightly rough when it’s absolutely dead dull, but what people are generally observing is failure to remove nicks. Not evidence that they’re a victim of a steel that has an underlying monte carlo simulation resident in it to determine when it will mercilessly let out a ball of line-leaving filth.

The failure to get a good surface or good performance of almost any decent tool is either abuse or quite often, blaming damage left in the tool on boogeymen.

Annealed 50-100

I’m looking for super bright and no defects at all on a test edge or test face of a board. This is after dry grinding a full bevel on a new plane iron with a 36 grit belt and then hand honing on an initial microbevel. This is rough treatment – 36 grit ceramic belts grind much cooler than regular belts or a wheel, but they are extremely aggressive. Those two probably go together.

Yesterday while looking at carbides in an annealed iron that’s then quickly quenched – as in, the iron is placed in vermiculite below the temperature where it could be quenched and then it’s allowed to cool slowly in a “sandwich” of pieces of metal. This does nice things to the carbide structure, hopefully making them smaller and more round.

I saw lines on my work. Just two. The annealed iron tempered a point or so softer than another iron I’d done the day before, so I was starting to guess at reasons.

The carbides looked like this.

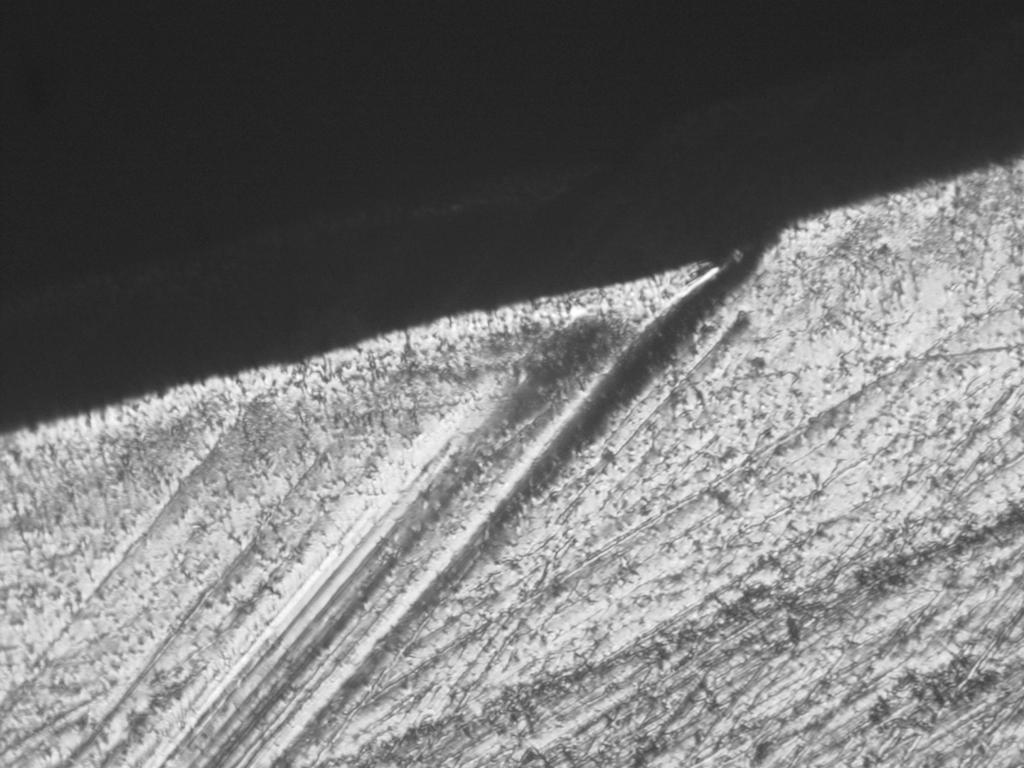

I scrolled the iron back and forth on the microscope looking for the folded over little area of poor results, and found this.

I guess it’s hard to complain about the quality of the edge when the diagonal scratch points the finger directly back at me. The height of this picture is only about .0095″ (just under a hundredth of an inch). This garish scratch is a couple of thousandths wide, but it looks pretty spectacular here. Interestingly, the edge seems to be closing over it.

The reality is, the steel isn’t at fault here. I’d like the iron to be a little harder, but could hardly claim the edge folded. This isn’t visible with the naked eye and I’m not sure if there’s even enough there to easily catch a thumbnail.

I fit in my own suggestion here – look to the sharpening first when pointing fingers at a blade or steel and thinking that it’s the blade. In fact, I can rarely count any time other than in rough lumber or knots or silica, where edge damage occurs in regular planing.

This idea of finding the right culprit and not being lazy and attributing it to something else is necessary for solving problems. Even though this is a simple one, the trouble is you’re your own feedback loop. If you have an iron that you often see defects without checking the iron, soon your supposition becomes truth with repetition. Except it’s often not true. That becomes even less helpful when you assert that it is when attempting to help someone else having the same problem.

I’ve removed this scratch, of course. But it’s not something the average person will get out of the back of an iron with 20 extra seconds in a fine waterstone.