Some time ago, I mastered controlling grain size and manipulating hardness of 26c3 and O1 steel. If this is your first post, you can find what those are with a google search.

The cycle that I published and used works for both of these well. I eventually sent samples to a metallurgist as I posed on a woodworking forum that I doubt that these ever vary by more than a point. This caused some people to call BS, but the hardness part is definitely true. Small variations in hardness around 60-64 cause a great difference in how a plain steel performs on certain stones. These stones are chosen because I know that one of them will begin to slow down on 62 hardness plain steel, a lot, and another will become slow on plain steel that’s more than about 65.

The metallurgist that I sent the samples to, I have a feeling, doesn’t care for my methods. I get that. I don’t normalize steel. I think for plain steel, it’s not necessary, but one has to be willing to snap samples and do some actual testing of results before determining that it’s worth sending something for testing.

When I sent my samples, I didn’t care that much about toughness, but the market for knife makers is much bigger than independent tool makers, so a lot of the testing has a big emphasis on toughness. Toughness has a lot of influence on whether or not someone will break a knife, and in the world of knives, a broken knife is a huge problem.

I sent the samples, asked about hardness, and then got the hardness results first. I was happy with them. The person doing the testing had concerns about the level of finish I did with the test samples (figure a fraction of a stick of gum size) because I had to precisely size and finish these little samples freehand. The tolerances are pretty tight for freehand. However, toughness results were also fine. Compared to hardness, both were as good as the metallurgist’s published results – that is, the toughness and hardness balance was good.

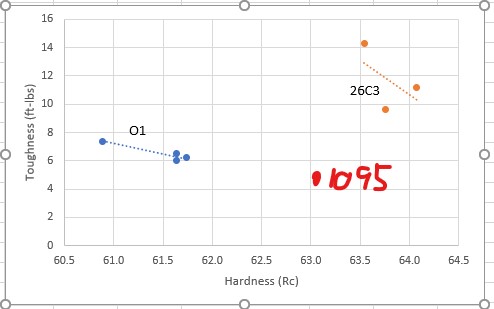

Here is the chart I received – I markered in the 1095 result. That will make sense in a second.

These results are no fluke, but I haven’t worked up and snapped samples for anything else, so I couldn’t guess anything other than hardness, which I can tell on a stone.

Here’s Where I Went Wrong

Out of curiosity, I then sent sample coupons of 1084 and 1095 later, and I heated XHP and sent coupons of that. When I first attempted to match XHP to V11 steel, I heated it very hot very quickly, but later learned that one of the reasons for high heat is to normalize. I’m not normalizing steel, so I didn’t heat the coupons to the same high temperature – in my mind figuring that since I wasn’t dissolving chromium but just hardening a sample, the high temperature wasn’t necessary.

I was wrong. The sample should’ve tested about 60/61 hardness at my tempering level. I’d made two knives with lower heat and they also seemed a little soft – you could just barely file the knives before tempering. They probably are – the test coupon came back 57.3 hardness or some figure within a couple of tenths of that.

I didn’t do my due diligence and attempted to reason into a change without testing it. I also never snapped 1084 or 1095, but just assumed that they would work just as well with the method that I use for 26c3 and O1. Well, they don’t. Off of the top of my head, I believe the 1095 averaged 63.1 hardness and 4.1 or 4.3 ft lbs of toughness. This was with a 400F temper, which is off the charts compared to published results without liquid nitrogen – something I don’t have. I did make a couple of samples of 1095 irons and they are OK, but will nick a little too easily and they were always harder than expected.

Why? I assumed that my prior heat treat cycle would just work and I didn’t so much as snap a single sample before sending anything off for testing.

Bad idea. 1084 was even worse. 61.5 hardness or so on average and toughness even worse than 1095, which is the wrong direction. I was unhappy with the results, but I don’t use any of these steels for anything, and for my own consumption, if I could bump an XHP sample to 58 hardness and just buff the edge to make up for the slight lack of hardness, no real problem. Toughness was good enough that breaking wouldn’t be a problem.

I was so pleased with the 26c3 results and that I’d made a claim of being able to make samples separately without varying hardness that I reasoned that there shouldn’t be an issue, especially with 1084, not testing anything. It’s always suggested as being easier to heat treat than O1 or 26c3. I’ll put aside XHP for now until I have a chance to run another sample to high heat and see if it completely thwarts a good file on a sharp corner. I failed to do something that only takes ten minutes at the most. Create a small coupon for myself and observe grain size.

Yesterday, I finally addressed the 1084 issue by making a couple of samples. I was shocked to find out both with grain snapping and testing with a magnet that what works for 26c3 in a forge is overheating 1084 – a lot. My eye is trained to see the point where 26c3 transitions to nonmagnetic. 1084 transitions (unexpectedly to me, but probably not to others) at a cooler appearing color. And then the second part of the mystery.

I intentionally overheat 26c3 during a quench. It takes about 10 extra seconds to do this and the result is imperceptible change in grain, but higher hardness. This is a nice thing when making chisels, and maybe not worth as much excitement making knives.

You can compare my results to a simple schedule of expected hardness and toughness here – I tempered steel at 390F for 26c3, two tempers. To be conservative, I think it’s also useful to check toughness a point or two softer than my averages as one end of the coupons is a point or two (it varied) less hard because it’s held by tongs and it’s not changing from hot to cold as fast in the quench. As in, my samples average about 63.8, but you could compare chart toughness at 62 and I think that’s fair.

Link to Chart of Expected Results

No matter how you look at it, the forge results are unexpectedly – at least to me – good. I never sent any of these coupons for analysis until I’d made 26c3 chisels that hold up in side beside testing better than anything else I have that’s not Japanese. But I still figured the samples would have some kind of shortcoming. They didn’t. I think I could do 100 of these on 30 different days and they’d very little.

So, What’s the Problem

The 10 seconds of chasing the heat higher to prep for a fast quench with 26c3, and the same color of thermal cycles that I’d trained myself to see by eye – both grow grain a little in 1095 and a whole lot in 1084.

If I’d done 10 minutes of due diligence and maybe 1 hour of various trials and a little bit of analysis, I’d have known not to send either sample, and in not doing that, I wasted my time and the time of the person doing the testing. But I think in advising against heat treatment, they may have at least gotten some enjoyment out of the fail. I didn’t get a chart for the second set, so I have no chart to display. The results, though, match what I felt with 1095 irons – hard and a little bit under tough for the hardness, and half of the toughness that they would’ve been done properly in a furnace a point or two softer.

I finally started this with an offcut yesterday. It took less than 10 minutes to make these samples. These are 1/10th of an inch thick bar stock. Having little for analysis, what I do to refine cycles (and did for 26c3) is snap samples along with some kind of performance test. The first sample is just whatever the steel is heated once without any intentional overshot and quench.

1084 – low temperature quick quench

Then, I will intentionally overheat a sample, and see what it looks like. This is with about 10 seconds of chasing the quench temperature higher than needed to get better hardness. Exactly what I do with 26c3, which shows no visual change in grain size.

This is a shock, and the difference in coarseness is drastic. I’m sure my tested samples were at least as large as this, but they may have grown during thermal cycling. I never broke one to look, but i have looked at 1095 in the past. I didn’t break one of these because I didn’t have extra steel after cutting samples, and if I did break 1095 at or near the same time, it wouldn’t have looked quite this bad. based on the test results.

The steel that is supposedly an easy starting point is no good for what I usually do. so, I made a third sample, increased the grain size slightly and then used lower temperature thermal cycles than what I do for 26c3, and heated it quickly a little hotter than the first sample.

1084 is my worst steel, so it’s the one I’m trying to conquer first.

I can take the unbroken part of the middle sample now and confirm that the grain will get close to #1 above, then I’m well on my way.

And sitting around and guessing at the various problems – a complete time waster (“was it the steel? Maybe it wasn’t rolled and treated well? Maybe it was mixed up with something else?”).

I don’t think any of those happened. I know now that I made bad samples because of an assumption that the cycle used for 26c3 should be fine for any plain steel.

If you are going to do heat treatment in a forge and develop something that’s relatively easy – The 26c3 cycle is easy for me – reflexive at this point – you absolutely have to snap samples and confirm that you can heat treat without increasing grain size before moving on to anything else.

I’ll post tomorrow or in the next few days about the very simple quick method of doing this.