This article is really about the first two new plane iron steel options I’ve seen in a while, viewed both in the context of older plane irons as well as vs. Lee Valley’s V11, which was long ago outed on Sawmill Creek. XHP and V11 are used interchangeably here. The two new options are CPM 10V (sounds like V11, but much different composition) and CPM Magnacut. The former, like XHP, isn’t a new steel. The latter is. But to my knowledge, 10V hasn’t been offered as a production plane iron in the US previously. Now, on to the story….

Somewhere in the early 2010s, Lee Valley introduced their V11 plane irons. Based on XRF (analysis) of the composition of those irons, they are either CTS-XHP or something very close. XRF analysis still doesn’t provide carbon content, but the rest of the alloying was on the mark.

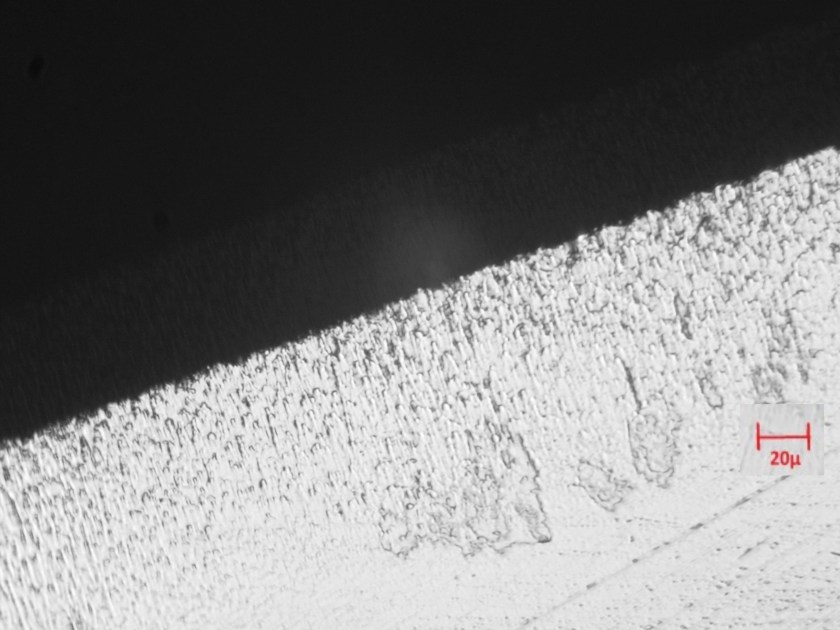

What is XHP? It’s a high-carbide-content and relatively high carbon powder metal steel that’s almost stainless. The carbides are generally carbon and chromium, without what is now more typical in popular steels – harder smaller carbides like vanadium and niobium.

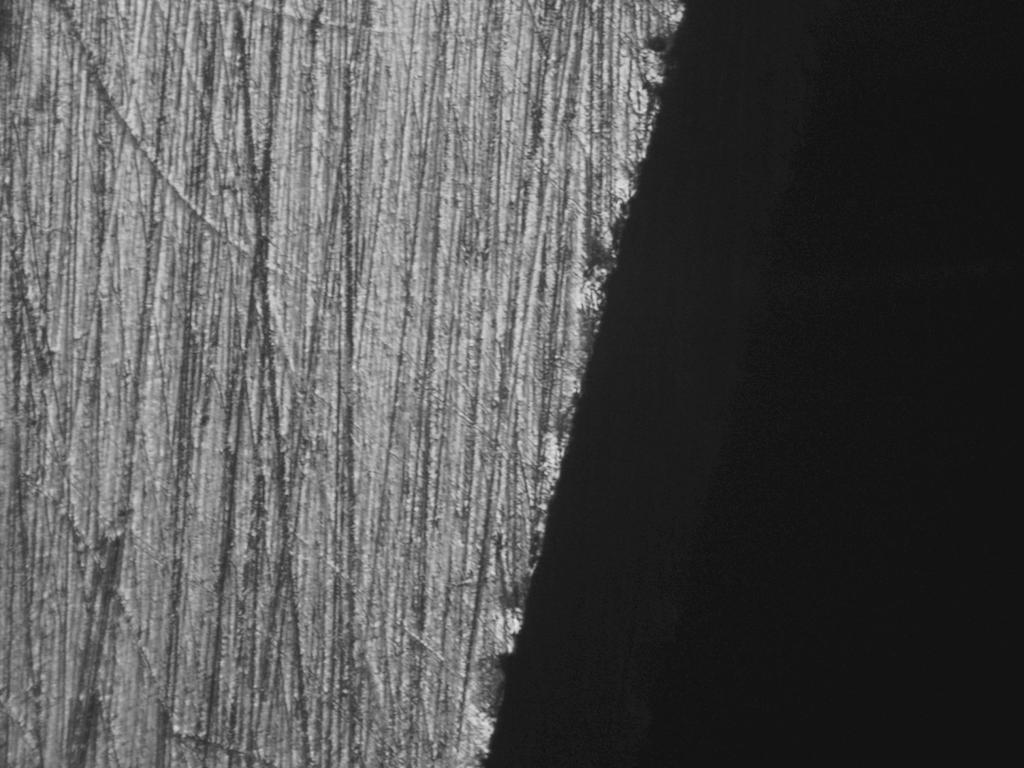

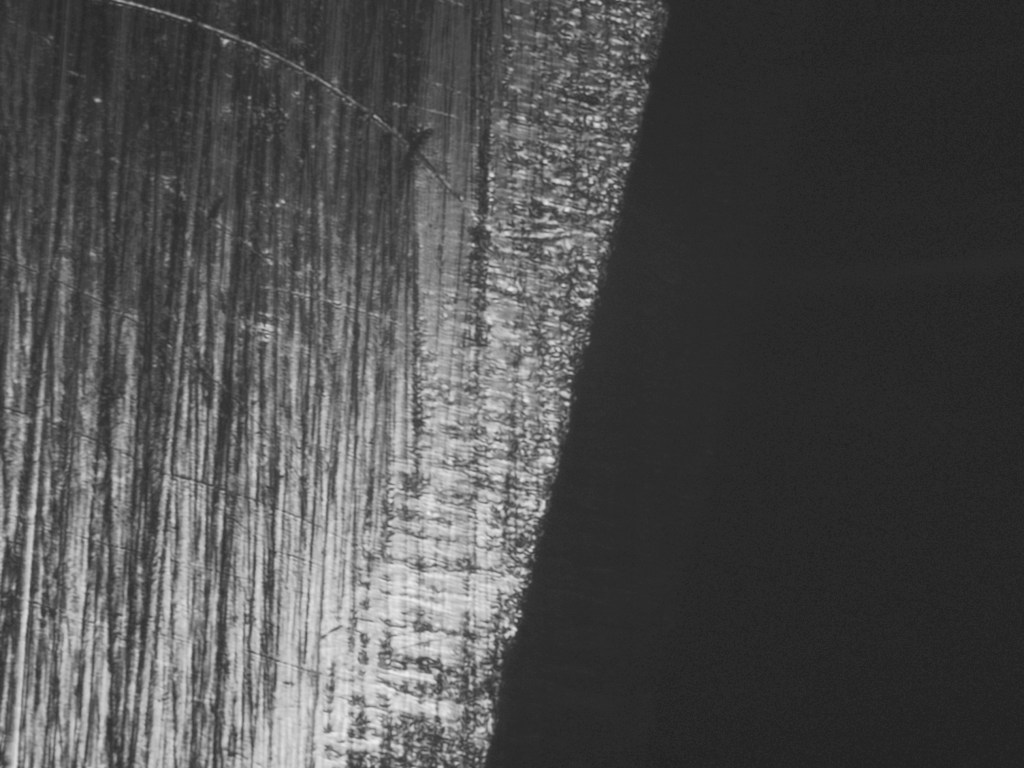

What XHP has is wear resistance. In spades. You can experience this by planing an edge with one of these irons and then planing an edge with O1 or A2 or whatever else you’d like, carefully preparing each iron the same way. You’ll find that V11 will plane about twice as far as a good O1 iron.

What I’ve found since doing the same thing is that there’s not much regular work where I can get that interval to hold up, but it should last longer. It will take about twice as long to grind and twice the effort to remove a similar amount of metal on a sharpening stone, too, but the abrasion resistance is double so the fact that it won’t hone as fast *when you’re abrading it* shouldn’t be a surprise.

V11 Came and Went and Little Else Followed

The rumor being passed around when V11 arrived was that “Lee Valley developed a new steel”. This is extremely unlikely given what they mentioned their costs were. It seems more likely that they tried various steels that already exist, and based on how they typically operate – sending tools to users for feedback before full production – probably solicited feedback.

It’s my opinion so far that if you really feel the need to dip your toes in something that wears longer than older steel, the inexpensive Chinese high speed steel irons and V11 are the only reasonable irons that return what they say they will. It’s possible that there is a powder D2 iron out there somewhere that could also be included in that, but if you buy a conventional D2 steel iron, you’ll find that it has large carbides that are poorly distributed and they will be big enough to fail even in sharpening and then the iron will be notchy or gritty and leave lines on work.

Before these irons, Academy Saw Works made M2 irons that were good ,and Stanley Hobart did, too. The former were too expensive for them to make economic sense woodworking if that’s important, and the latter probably are only easy to find in Australia and maybe no longer easy. None of these were ever widely sold, though. There were also other small batches made in the US with CPM steels – 3V and M4 at least.

In my opinion, Lee Valley was concerned that someone may make an iron with the same steel if they had just called the alloy what it is. I don’t think this is likely, but at the time, who knows. Why wouldn’t it be likely? XHP isn’t really widely available and when it is, it’s very expensive. The option when steel isn’t available is to order a melt of your own, but the average small maker isn’t going to do this either. I don’t know what Lee Valley does, but I would imagine that they do enough volume to order or trigger a melt being done for their order. The rest of us, you can get CTS-XHP at retail from a retailer that specializes in carpenter products (I don’t recall the name, but if you search for XHP bar stock, you’ll find it – I only remember the background is red at the site), but you’ll find the bar stock itself will be $25 or so per iron that you make. This is *a lot* of money compared to other conventional steels.

So, the fanfare came and went, and the market got little more educated, it seems. One of LVs fans suggested at one point that I should “leave the steel to the experts”, which I thought was humorous. A few more educated individuals called out the idea that the composition of a steel being secret was nonsense in a world where it’s touted in knives, and XRF tests are often done publicly to line out retailers who sell things that are too good to be true.

I was pleased enough with a test planing clean wood that I made myself a set of XHP irons, tested one against V11 and found it was comparable. And then, I started back to regular woodworking and found that once the wood wasn’t already clean wood, I couldn’t get the same interval, and the chipping and other things that can occur in regular work took longer to hone, and I eventually just went back to plain steels. I also sold off the three V11 irons that I’d gotten in the past – no bueno for me. For a beginner who has a prescription honing method and will never progress, maybe that’s different. I still have my XHP irons, but they’re not in any other planes.

From time to time, I’d see custom made irons sold on ebay but consider the cost mentioned above, then the cost to get a small batch heat treated and ground and what will you find? irons for about $100. We’re not the knife community, and LV charges about $10 more for V11. They’re not lining their pockets – in my opinion, they have been the only reasonable option if you’re not going to learn to sharpen faster and find out why plain steel irons are all that really ever sold in volume. And most woodworkers are going to imagine woodworking more than they do it, so this is probably most of the market.

So, from my point of view, that’s where we are. Lie Nielsen is still using A2, which I would assume is for their convenience because it moves little in heat treatment. They may tell you otherwise, and so too may other retailers. A2 does cost a little more in bar stock form than O1, but we have become so lacking in skill as a society that heat treatment services are cutting back what they will heat treat with several posting notice that they will no longer heat treat O1 steel. Lie Nielsen did mention that their heat treatment service or perhaps a separate service informed them, too, no more O1.

So, What’s the Point?

Two things – First, I’ve found over time that the steel in the iron doesn’t matter that much if it’s not defective. Your ability to use a plane properly will dictate how much you get done, and on the chisel side of things, V11 isn’t that great in my opinion. What it has is hardness, which often allows beginners to get an easier sharp edge, and hardness does help a chisel in a side by side test. However, when I did a chisel test making an article about the Unicorn method, i didn’t find V11 to perform better or as well as some other lower cost options. This isn’t a surprise – abrasion resistance is a cutting or planing boon, but not so much for chisels. If you imagine yourself paring a chisel until the edge is round, it’ll never happen.

Second, over time, I’ve realized that most of the people who talk a lot about hand tools use them relatively little. They become indignant if you suggest that, but it is certainly the case that if you don’t do much work rough to finish with hand tools, you’ll have an unreliable opinion about what hand tools are actually capable of. I would refer to this as some woodworking, but a lot more imagining woodworking. Imagining woodworking leads to things like focusing on backlash, scanning tool reviews in fine woodworking and buying what’s recommended. Woodworking is finding something acceptable and learning to use it well, focusing on learning incremental little bits that make “well” better and better.

An example of woodworking vs. imagining it and what the result is is using a plane with a cap iron. Few people do it, but it’s at the core of getting a volume of wood planed between sharpenings. A common stanley iron used with a cap iron will do several multiples of the volume of work that a V11 iron will do without using the cap iron. Something I also found when I believed the converse early on – even a wooden plane with an iron that wears less long than O1 will outwork a metal plane *with the cap iron set*. That doesn’t seem like it should be, but it is the case.

Another example would be use of chisels – a good worker can use any decent chisel and figure out how to set up the chisel so that the edge doesn’t fail. This is rarely discussed online. I’d call this the magic of experience. Sometimes we don’t even know what’s causing the improvement, but it occurs just with experience. Sometimes the changes are conscious.

Long story short, if there is a mention about how revolutionary harder or more abrasion resistant irons are, I generally assume that the person making the statement hasn’t done much hand work, or if they have, it’s been a narrow bit of work done after shoveling wood through power tools, with significant sanding always being the final go after the plane finishes. If that wasn’t the case, we’d see a lot more posts asking how to stop iron nicking.

So, is there really any need for someone to work their way through lists of steels that aren’t designed for woodworking and see if any are “better”. I think V11 offers a fair bargain in some cases (effort to grind and sharpen is in proportion to more plain steels as long as work doesn’t nick the edge). Higher hardness PM D2 would do the same, at least as well. So would high quality M2, which could be done inexpensively and just isn’t. I think the answer is no – but someone could, anyway, for curiosity and also because while few will admit they’re just practicing escapism with hand tools, most are.

And just recently, I noticed there are now at least two available small batch options – CPM Magnacut and CPM 10V

Magnacut is a small particle / small carbide stainless, and 10V is a higher carbide volume steel that’s “kind of” similar to V11 except that the carbide volume is mostly vanadium carbides and not chromium. Magnacut is vanadium and niobium.

What does that mean? Both of the steels above have smaller harder carbides than V11. One technically wears longer (10V) and one doesn’t (magnacut).

Magnacut can achieve about the same hardness as V11, is far more stainless, and is tougher with finer particles. Going deep into the properties probably isn’t worthwhile here, but it would appear that Magnacut will have an edge life about 90% of V11/XHP in abrasion tests – only time will tell if it handles rougher work better than V11.

10V can technically reach edge life intervals of 40-45% longer than V11. This is bonkers long. It is also going to be tolerant to heavy handed grinding as the tempering range is above 1000F. You can brown or blue the edge of it.

This isn’t true for V11 and Magnacut, which will both hone and grind with more heat than more plain steels, but they won’t tolerate more heat.

The Magnacut irons are made by Lake Erie Toolworks, and the 10V irons appear to be a test run by a toolmaker in Chicago. As of this writing, the former are about $90 with tax and shipping, a little more for wider irons, and the 10V irons are $50 – but only available in 2″ size.

I have bought one of each (not given, not offered to test, nothing like that – I just bought them full price. Anyone reviewing tools to make a video or get free stuff – no bueno). I think either has potential merits, just like V11. based on some initial planing and sharpening with each, I don’t think they’ll be great for rough to finish work, but people like me aren’t the market for these irons, so I’ll address how well they work from the context of someone who would also buy V11 and feel like it makes a big difference.

Where to get Information on the steels

Larrin Thomas has the most accurate “usable” information I’ve seen anywhere. Larrin isn’t a woodworker, and I haven’t convinced any knife makers or other folks that maybe there’s something different about edge properties in woodworking tools, but the information on the site is generalized, so it won’t matter.

It’s semi-technical. That’s what you need if you want to actually learn anything. If you want a one paragraph narrative that uses word like “super fine grain” or “really tough”, without explaining those things, you can read woodworkers or watch youtube channels who really are only there to sell you things.

For information about XHP, 10V and Magnacut, see the following:

Knife Steel Nerds on XHP

Knife Steel Nerds on Magnacut

Knife Steel Nerds on 10V

Lastly – 10V is not new, and it’s widely used for dies and other industrial purposes where high wear is needed. Magnacut is new – it’s something Larrin developed and if you want to read further, you’ll find that it’s more or less a Stainless version of CPM 4V – that’s loosely put. 4V would probably be a good option for woodworking, but while magnacut and 10V bar stock is expensive, 4V is hardly any less expensive itself.

XHP has been around for a long time. You can ignore Larrin’s distaste for its carbide size – knife steel fanatics are obsessed with toughness, but there are other properties that are ahead of it to a reasonable point for woodworking. We don’t put tools in tree stumps and then see how much energy it takes to bend them over and break them.

Oh, and if you’re wondering about XHP/V11 being “almost stainless”, for woodworking purposes, it’s stainless. Even for reasonable kitchen use, it would be – I’ve made knives out of it, too, and while it can take very light staining in regular use from certain foods, I’ve left it unwashed in a drawer to find no rust later.