This isn’t something I’m currently doing, but I see enough used items for sale, and questions about this or that new retailer doubling the price of tools and selling them to Americans and Europeans that I think it’s worth noting.

I gather in the early 80s, there were a few enterprising American tool sellers who realized they could go to Japan and buy a bunch of Japanese style tools, and sell the woo. The woo is the hook, and a horrible yen value at the time made casting that hook worthwhile. I wasn’t woodworking then, so I’m speculating having seen the Mahogany Masterpieces video regarding makers. Every maker that the tool flipper who made the video sold was of course “the best made”. Ouchi, and I already can’t remember anyone else other than Hisao making what look like macassar ebony plane dais (but his work rate was spectacular and he was mortising the plane bodies with a stub handle 6 pound hammer!!!)

I will be 50 in a few years, and I remember the pre-internet days well. If you’re 30, you may not. Even if you’re 35, you may not. You may not remember how many times you’d read an interesting catalogue if you got such a thing in paper and had it to reference. How else would you get info? I see the whole Japanese culture thing in the west as a bit of an oppositional thing. People looking to escape Reagan or Carter and wanting to imagine another set of ideals is better. That’s a time-neutral thing. That and the desire to have something different or be different or feel like you know something exclusive. It gets really tacky when someone who has been woodworking for 1 year starts using very specific Japanese terms mixed in with English. I never really cared for that no matter the language, and where I grew up, we had a German themed gift shop called “Das Gift Haus” in town. “Gift” in German translates to poison or toxin.

I’m getting a little off track – when things are seen as being more than they literally are and you have to be the cool person knowing all of the right names in foreign languages, I’m out.

But the tools are fine.

There is less of a transitory nature from one generation of the tools to the next other than the Western influenced push for the very neatest of neat work or the flashy dragon or decorative stuff. That doesn’t look very Japanese and it probably isn’t. When you see boasts about Kiyohisa, I doubt that Kiyohisa’s waiting lists has much of a share of customers outside of a bunch of “old white guys”. There may be exceptions, but much as someone in Japan on the shaving forums said in response to a shaver hoping to find Kamisori (japanese razors) on the ground – “it’s hard to find them on the ground, they are mostly made for export”.

I grew up in Gettysburg, PA. I guess you didn’t find too many kids wearing civil war hats and shooting pop guns if the kids were local, too. Plenty of other kids not from there did. It’s weird to me when a tradition becomes profitable mostly based on outside customers.

So what?

I’ll say it flatly. I don’t think any dealer who sells mostly to westerners or sells in the US is worth patronizing. You get things like Z saw blades that are $5 each in japan selling for $20 here. You get Tsunesaburo planes selling for more than twice the going rate in Japan, and the narratives about the steels beyond the typical Yasuki/Hitachi White is outdated and the flaws of some of the steels aren’t well described. You want super blue? Better like a chipping edge or one with disparate carbides.

Do you lust after Togo Reigo? I think if you do, you’d regret having it as a daily user. Steel alloys are not hard to make in custom melts if they are ingot types. Andrews didn’t keep selling Togo Reigo to Japan, or license it or whatever was done, not because it was a secret that was kept away from society by unusual circumstances – it’s gone because there is no market demand for it. What’s so special about it? I don’t really know – it’s a very high carbon steel with Tungsten chromium added. A recipe not too far off from Blue 1. I don’t care for the blue steels, either – Tungsten was added to steels as the “it” carbide in the early 1900s because it improved wear resistance and in theory, will be broken up and dispersed at typical forging temperatures. In most of the micrographs I’ve seen, the dispersion doesn’t actually happen, and tungsten carbides exist in varying bands or large disparate carbides – exactly what we don’t want. I saw this when testing plane irons with the Blue steel Tsunesaburo replacement plane irons. They look like they are cut and blanked out of prelaminated material, but I saw the same edge behavior in traditional Japanese irons.

The woo will be pushed at you further with suggestions of just needing to find the right smith. Well, the odds aren’t great for someone actually putting anything like that into practice. White 1 and White 2 will be easier, and they’re overpriced for what they are in bar stock, but there’s not much in tools and if there is demand for them, Hitachi can make more.

White steel doesn’t need much. it needs to be normalized, grain shrunk and heat treated properly. It comes in bars, doesn’t need a special forging process and probably would gain nothing from such a thing no matter what. You use it, if it’s heat treated properly, the edge wears evenly with no surprises and it sharpens well.

But I guess it’s boring – and there is truth that the edge doesn’t wear long. Less long than O1. This is a problem only for beginners.

But you’ll see a dizzying array of various “special blade steels” and whatever else that you really can’t get a grasp on. There’s nothing special about any of them.

A Case Example

First, before the real example – I have had tsunesaburo’s super blue plane, or one of them. Someone on ebay years ago was selling stock for a hardware store and at the cost of $400, I couldn’t resist. New plane, presentation box, nice red oak dai. Disparate carbides, chippy edge. No good.

At the time, I bought a $200 plane from Alex Gilmore, and then a matched blade and subblade from Ogata. One of the things people will say is that a maker can make steel very hard and very easy to sharpen. The trick is, the steel’s not actually that hard if sharpening is easier than anything else. Alloying and hardness control sharpness. One guy’s plain carbon steel doesn’t sharpen twice as fast as another’s without a big difference in hardness. the Ogata blade that I got was somewhat soft – I’d guess 61 if I still had it. It was about $250.

Alex sells nothing cheap. You can think about the cost, and get the idea that it likely didn’t cost much in Japan. At the time, you could find Ogata’s planes for not much or you could buy them from Iida (who is now out of business) for about $500, which was probably a cushy flip for Iida, and there was scuzzle (short for scuttlebutt) about whether or not Ogata was still in business. Either way, the underlying issue here is that almost all of the makers can make blades faster than they can sell them, and the cost of materials in a blade or blade set isn’t much. The constant flow of unused planes under the radar for both Ogata and Takeo Nakano made it clear -the issue isn’t rarity, it’s demand.

The Ogata blade was fine, but the unknown make plane that I got for $200 at the same time had a much thinner hard lamination and was at least as easy or earlier to sharpen, but the lamination was harder. It was a better iron for actual use. That ended my desire to find a blade from a specific maker, but rather find one with characteristics. Relatively neatly made, visual evidence of wrought iron backing as the wrought iron hones easily, and a thin hardened layer (or hagane – if someone forces you to use words that aren’t in English). I guess I’ve bought maybe four planes since then, sold a lot of what I had, but on average, the blades with a dai were about $150 and varied from 70-80mm in width. Buying older planes lowered the chance of getting a dippy alloy. I don’t think any of the four were something other than a plain carbon steel, and probably all were yasuki/hitachi white because they weren’t new enough for westerners to dominate the customer list.

The same was true for chisels. Buy chisels relatively neatly made as a set for about 1/6th of the cost of new, and make sure they are neatly made enough that they’re not hardware store fodder. there isn’t anything that looks like Kiyohisa but there are a lot of nicely made chisels for inexpensive amounts and the edge quality being just what you want is at least 50% chance. This is no worse than buying new sets from a dealer who tells you that you’re getting something special, but you get the tools and you can’t figure out how to set them up so that you can just use them. If Japanese chisel are hardened and tempered properly, they aren’t picky about which stones are used, they aren’t hard tempered and chippy, and they’re not soft, either. You just sharpen them and use them.

Here’s where Ogata comes back around. I don’t order things from Japan woodworker, but for a while, I guess I fit their demographic. I did order a few things when I was a beginner but when Stu Tierney started selling to-order Tsunesaburo planes for half of Japan Woodworker’s price. Same for Iyoroi tools – you could get them from a Japanese seller for half as much if you wanted to climb up the ranks a little bit and get something other than the blocky entry level chisels sold at woodcraft (who now owns JWW)….I was out. but somehow, I got an email or a catalogue (can’t remember which) that advertised that Japan Woodworker was now going to sell Ogata planes and that Ogata retired and you couldn’t get them anywhere else.

What am I supposing? maybe Ogata did actually retire, or the shop closed if there was Ogata + employee(s). Of course, you could see that Tomohito Iida also had them for just under $500. His relatively high cost of everything didn’t meet Japan Woodworker’s standard and the Ogata planes were listed for $780 (!!!!). I have no idea what it cost to get the old blade stock and have dais made, but I’m going to stick my neck out and guess that it was less than $200 per plane total. If Japan Woodworker wants to tell us their actual cost, I’ll gladly post it. I figure that Alex doubled the cost of whatever he sold me, because other things (like Atoma plates) were double the cost of retail in Japan. But Alex is a small business specializing in person to person sales and he travels back and forth. You don’t get amazon drop ship service prices for that.

Does Japan woodworker still exist in its original form? I don’t know – it looks like the items listed on Woodcraft’s page have declined and I see only one sort of commodity grade plane.

Iida’s probably response to Japan Woodworker was humorous. he took his website down for “redesign” and when it came back up, the Ogata planes were about the same price as Japan Woodworker, and a maker who I appreciate, Takeo Nakano, also up from $500 to about $800. Nakano was sort of a straight forward make that was sold based on the maker’s claim that the price of planes should be something that an actual craftsman could afford. they went from being $300 to $800 in a hurry, but Iida would also sell them back door on ebay on straight up auctions and sometimes they would bring $150-$200. I got one, nothing wrong with it.

The price is “what will you pay”, and the market for “let me see what the max I can tolerate” is generally not in Japan. I think this revival has been good for the small makers in Japan, though – the outlook was probably pretty bleak supplying only customers in country, and reliance on a few makers being designated of historical significance (and subsidized by the government) would’ve been the thread keeping things going.

So far, as you will note, nobody has run out of anchor chain, old bridge wrought iron, or even Andrews Togo Reigo, which was never needed in a fresh melt because the original supply is still being used.

What Brought this Up?

I saw a listing of an unfortunate individual who had bought a few expensive planes, and was hoping to sell them on a woodworking forum for $900 per or something. They are planes that I’d expect to pay a quality equivalent of about $300 in Japan.

The whole time this Ogata debacle was going on, the yen was weakening. At the worst, I paid for tools at 77 yen per dollar or so. As of today, it’s 149. That’s easy math – if you’re paying in dollars or buying in dollars as Iida was charging, the impact of the price is bolstered even further. At the time that I saw Iida declared bankruptcy (a mystery, but you never know what’s going on behind the scenes – one high margin business can be brought down by personal habits or another part of a business eating cash – ask farmers who loved International Harvester tractors). Anyway, at that time, the yen had long been 120 or above and I thought maybe at some point, Iida would adjust his prices downward.

Let’s put this a little differently – I bought an Ogata blade and subblade from Alex Gilmore for what would’ve been about 20k yen. When Japan Woodworker decided to tell everyone they were the only source – despite easily searching and finding Iida also was selling the planes as a stock item – the equivalent yen price was about 100k yen. If you can make a market, either distributor or retailer is doing well there.

Seeing people in europe or the USA try to sell unused planes for $900 makes my heart hurt a little bit. They’ve been had. Just as I bought a green finishing stone from a US seller for $425 eons ago and you can find the same green ohira tomae in japan for $165 now. It wasn’t a great stone – it was available because Ohira mine is open, and sold as a “chosen and selected” stone to people who didn’t know any better. Including me.

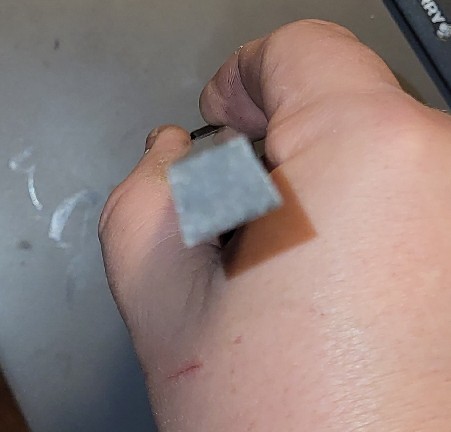

I traveled to buyee, which is a proxy service. They translate japanese auctions, take in the goods, make sure they match the auction when you buy and then ship them to America.

It’s still the case that a lovely unused 70mm plane can be had with a subblade, neatly made ledged dai and box for about $200. It’s still the case that for the average set of 10 chisels, you’re looking at a cost of $100-$200.

My advice is if you want to dabble with Japanese tools, read the stuff about them in English, and buy them from someone who only speaks Japanese. Your chance of using the planes and saws for long and to make much is very low against the chance that you’ll spend a lot of money buying.

They’re tools in japan, not presentation items where you boast you had to wait 7 years to get them. they are used like tools there, and stuck in shadowboxes in the US with bogus information about 220F tempering temperatures.

The one thing that remains true in all of it is the hitachi white is good stuff. It really does have the potential to be a couple of points harder than fine western steels and not be chippy, but someone has to put in the effort to heat treat it so that it’s all it can be.