A few weeks ago, someone emailed me and mentioned they had a LV shooting plane, and they couldn’t get the iron to hold up with a V11 iron. This request was after getting a replacement, which was better than the original iron but still not suitable. I haven’t bought a V11 iron in a very long time, but when I did, they were tempered a little hard. So this was kind of a surprise.

Shooting is more like chiseling than planing, and when I tested irons even with wood in the vise planing end grain, the wear life of V11 vs. O1 wasn’t nearly at the same interval. In long grain with no challenges, V11 doubles good O1 if the V11 and O1 are in the same hardness range. You can’t actually get this interval in regular work, but in a test situation where you’re just continuing to plane clean wood that’s already planed, it’s pretty spectacular. LV’s O1 isn’t really a good comparison because it’s too soft – my opinion, of course. I don’t know what woodworkers do with 59 hardness steel in dry wood, but issues where there is an edge strength need – like chiseling or shooting, will relate to accelerated wear.

But V11 was a puzzler, just from what I remembered. I remember it lasting about 15% or so longer planing end grain in a vise, which is a more gentle operation, but certainly nothing that would lead to it not holding up.

I have made XHP irons that are 61/62 – same steel, as far as I know. if the steel is below that or even at 61, it does change behavior a lot and will deflect more easily. This can be seen in knives, but a knife isn’t shooting end grain and you can tolerate more deflection.

Regardless, the request was whether or not I could make an iron that wouldn’t fail.

I accepted the challenge, but then realized all I have in 3/16″ steel is O1. Or that was the case. I figured I’d make an O1 iron pushed a little to 62/63 but with a strong temper at that to avoid chippiness. What does this compare to? I match Hock’s 64 in the one hock iron I have by tempering to 350F. it’s tempting to be impressed by that in test shavings because the iron is very crisp. I suspect the actual hock irons might be pushed less in the quench and be tempered just below that, like around 325F, but I could be wrong. It doesn’t matter that much. This test isn’t about duplicating Hock, but rather knowing that if O1 is to better V11, it will need to have edge strength that comes from hardness, but not chip easily. Tempering my hock iron would’ve improved it for day to day use, but I broke it instead to get a look at the grain. LV offers nothing similar, which gives me a lot of options.

26c3 is the apple of my eye for chisels. It hits 64 hardness with a strong light straw double temper, but upon looking it up, you can get it in .14″ or .25″, and no 3/16ths. O1 steel is, of course, an option, and so is 52100. I don’t love 52100 in irons for planing long grain, but I know I can get it to 64 after a 400F double temper as well, without brittle grain growth.

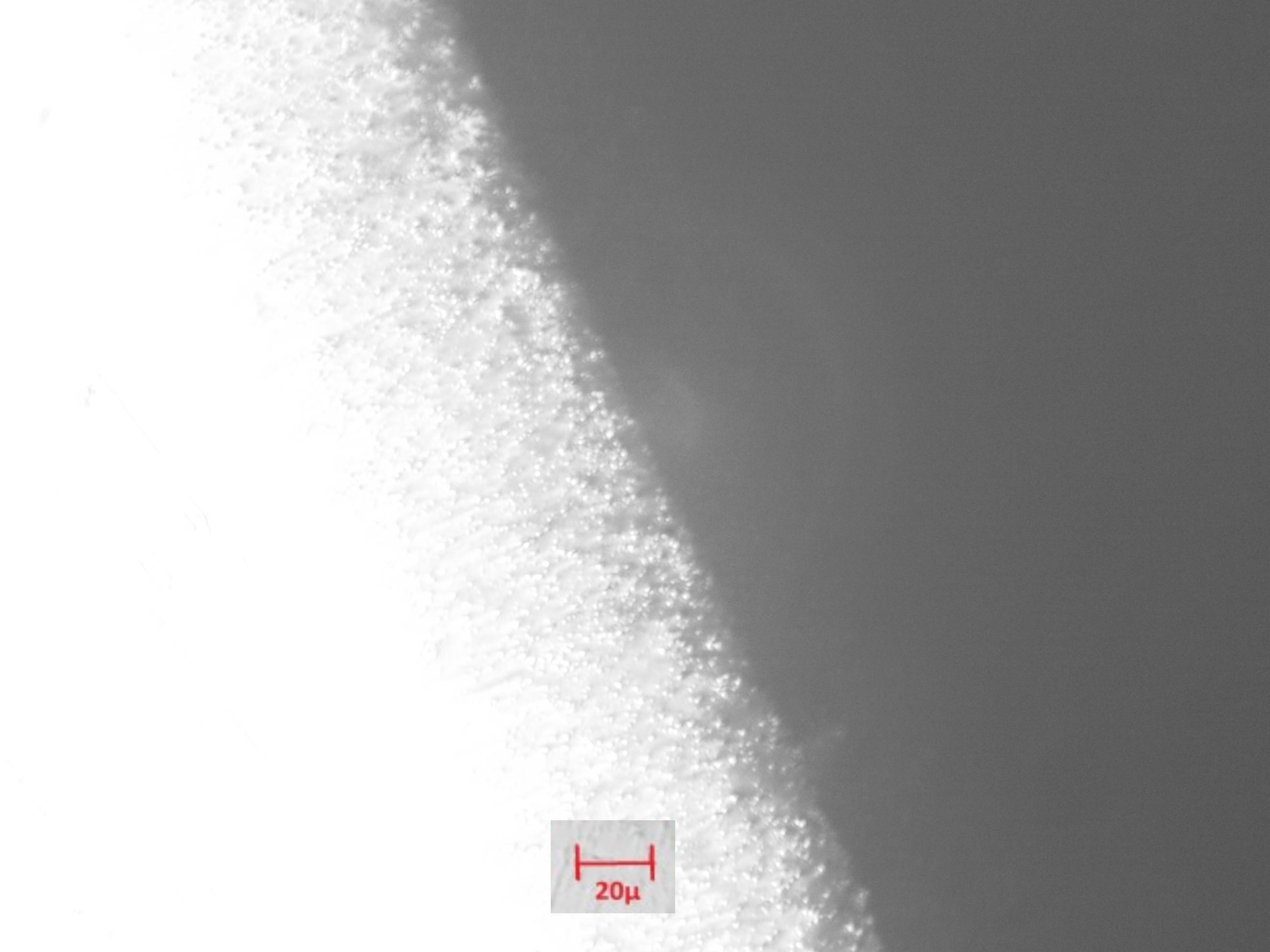

But looking around, I’m chasing comfortable hardness without having to freehand grind and then float/flatten/file a .25″ bar stock to 3/16ths or close. So 26c3 is out – unfortunately. There’s one other option, though, which is 125cr1 – a similar composition steel but not made with the high cost process (remelting, which improves uniformity at a microlevel) that 26c3 gets. I’ve fiddled with 125cr1 and you can see in snapped samples that some of the alloying isn’t as well distributed, or at least that may be the case, and if that’s not the case, something  .

.

that’s 125cr1 at high hardness. What are the white bits? Talking with a metallurgist in the past didn’t help. the internet creates too big of a distance and a metallurgist will just assume you did something wrong and pose 10 ways you could’ve failed and insist “you don’t know”. That’s correct, I don’t know – I’m not staking a professional reputation on this, I want to know if it could be a “not worth using it” it matter, and have seen the same thing in some samples of 52100.

What happens when it looks like this rather than uniform gray? Well, in 52100 and in the 1.25% carbon 125cr1 above, the steel needs to be pushed a little further to get full hardness vs. very clean looking samples. Speaking of, clean is a word being used here for how these look – the 125cr1 melt sheet shows that the actual composition is really high quality and aside from a tiny 0.25% addition of chromium, the other stuff is pretty close to being in line with hitachi white 1 spec.

I decided to buy 3/16 125cr1 and give it a try. I’ve seen defective 1095 first hand – when there is a defect for real, it shows up in the edge. This stuff might not, and there should be a potential to get edge strength.

I asked the person making the request to send the V11 iron so that I could hardness test it and so that i could use it as a template. I don’t care for the aesthetics, especially in the slot, but I don’t have the shooting plane – did at one point, but don’t now.

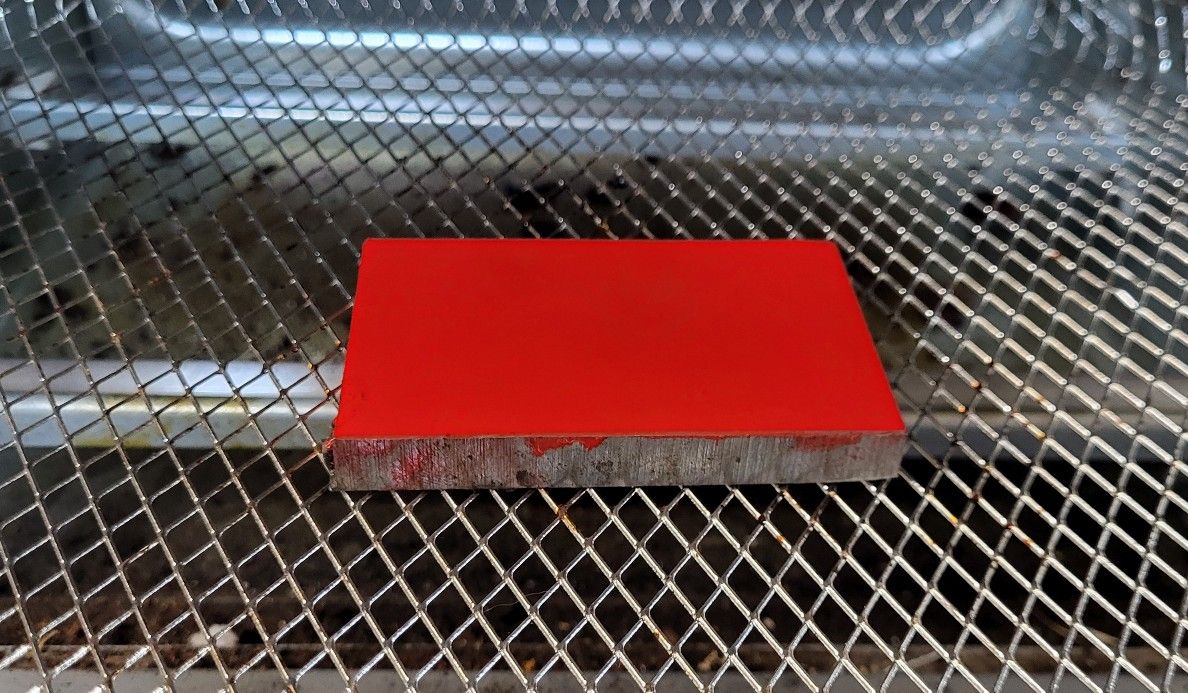

My first attempt at making one from 125c1 is this:

This iron came out a point softer than I’d hoped, so I tempered it at 375F or so instead. that left it at 64.5 hardness in the middle. It’s not hard to hone because there’s little in it for abrasion resistance, but you can feel it’s hard. the black is 95% scale from the forge, and to make it uniform, anywhere I dinged or marked the surface, I just put cold blue on to make it uniform. I can’t see a reason to remove it. But I’d sure like the slot to be rounded and not to a point. it would look better and be easier for a hand maker to make vs filing this in.

I sent this iron off, and the first reports of it are solid – it’s better.

I decided also that maybe I’d send one to Bill T – who some of you may remember from forums. Bill does a lot of woodworking and I can count on him to say “i don’t see the point” if I make something I think is better but he doesn’t see that it matters. that kind of feedback is valuable.

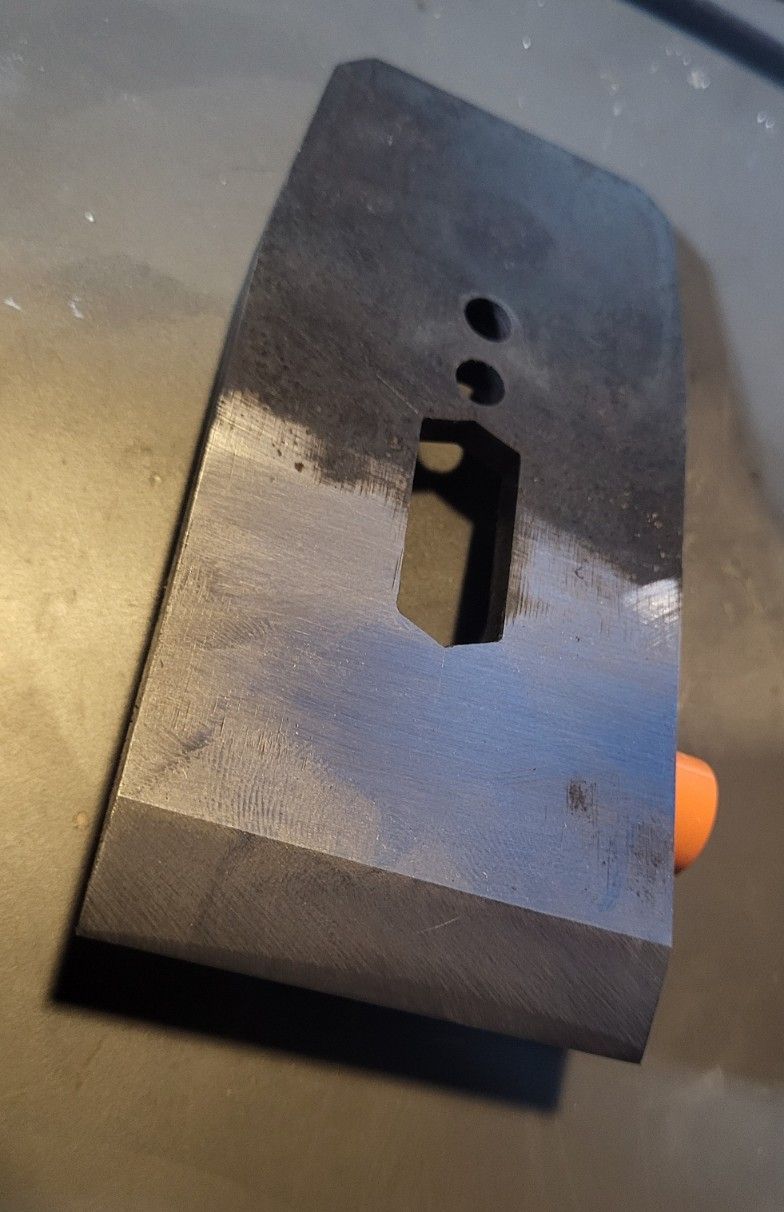

I pushed heat treatment harder on Bill’s, fiddling around to try to get as even of heat as possible visually. The thickness is really reactive with the induction forge (of course i’m not sending these out or using a furnace), so it’s a challenge to get the sides and center to the same color for the same amount of time. When you push heat for a short time, it has to go well above the furnace schedule protocol, but you’re playing with fire doing that despite using magnetics (har). A little too much for 10 seconds too long and you can have grain growth. The second iron looks like this:

I don’t sell stuff to Bill, and admittedly, the geometry on the sides of this second one isn’t so accurate – they’re not straight on the edges but rather a little bell shaped – oops! But this one came out of the quench after that kind of fiddling at 70 hardness, and it tempers back with a double 400F temper to 64.5. It makes no sense to send something with a little grain growth to someone, so I was pondering making it over again and realized that it’s not a sold product, so I can just set up the edge, and then strike it with a punch and break it out:

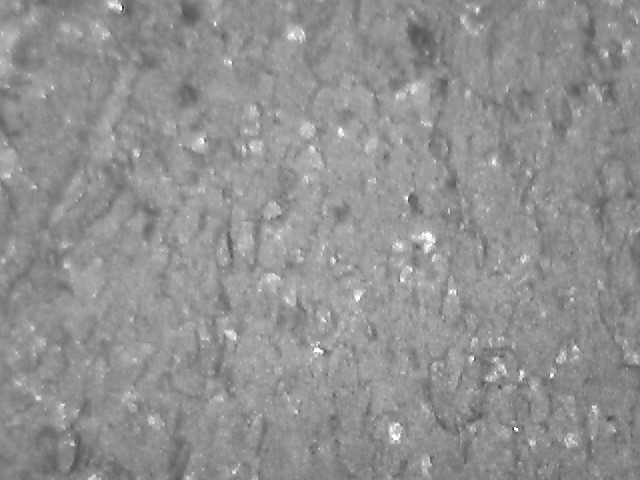

This broken out section show is about half of the width of a BB – looks fine. what you’re looking for in a snapped sample is something that looks like coarse silicon carbide with shiny facets all over the place. That’s large grain. none of it shows up here. Also, where did the blotches go? No clue. I haven’t noticed extra heat to fix the issue in the past, but maybe it does.

I’ll see what Bill says. As far as I know, he has no issues with his.

Does this experiment to beat Goliath offer some kind of eureka if these are notably better? Not really – nobody is going to make these on a commercial basis because the steel is water hardening, and on top of that, the furnace samples of 26c3, which are sort of a ceiling for this, don’t have as much toughness as the forge samples I had tested. that’s rarely going to occur, but I think surplus steel simple carbon steels probably have the potential to be better out of a forge.

So, How did the V11 Test?

First, I looked over the iron when I got it, and I didn’t see anything unusual in the edge in terms of how it was set up. I did see some artifacts of deflection that still existed behind the honed edge from prior damage. That’s unusual. I tested the iron a little hastily and got 62 hardness as a result. But going back later with four more strikes, it’s a half point less hard than that. I don’t know if that matters, but using a plane for shooting in a steel that’s not that great with edge stability, not much hardness can be sacrificed.

To make sure the edge itself wasn’t at all overheated, I filed it. Nope, damages a file – fine there, and no color anywhere on the top or bottom side of the bevel.

I really don’t know, and I don’t have any real suggestion about what might be better aside from 64 hardness M2 as an offering. That wouldn’t be that expensive, and it’s a steel that comfortably hits that hardness, and on top of that, it would be hard to overheat an edge. It’s not hard to overheat V11, which isn’t high speed and grinds at half the speed of O1, retaining a lot of heat. I think it’s just an odd choice to offer a soft O1 iron that would probably be good at 62/63, and then offer a steel that is highly abrasion resistant but may land in the hand of the user at 61 hardness and also grind a bit warm threatening loss of even that.

Who knows.

If anyone is concerned about the tracing of the center slot including the characteristic V, don’t worry – neither of these irons is being sold. Is that a trade dress thing? I don’t know. I could make more of these, but they will not look the same if I do, they’ll look a little more human did in elements.

Also, there’s a little Easter Egg in the second iron – look below the slot. I pushed the limits on temperature, but heated only a little past the slot and then quenched the entire length of the iron chasing hardness. The result is a tiny hairline crack, but one that doesn’t go far, and fortunately it isn’t on the bevel end.