1095 is a steel that most people think of when they mention modern handsaws or card scrapers. Or perhaps older knives and some current kabar knives. Except none of those knives are actually 1095. They’re a modified alloy with chromium and vanadium.

But, you can’t really get that publicly.

I had a relatively lengthy post – OK..all of them are – about solving 1084. Solving 1084 had to do with just how fast grain grows in 1084 if it’s overheated a little. Other steels seem to like a fast overheat just before quench, and 1095 is one that doesn’t suffer too much. but….

What’s wrong with 1095?

You’ll probably never see 1095 in commercial tools other than spring steel. It’s really cheap, and it tends to have some of the manganese (hardenability) replaced by chromium, presumably because just adding carbon to 1084 results in a really brittle steel.

Chromium takes up some of the slack for missing manganese in terms of hardenability, and 1095 is what you would call a high hardness steel with poor hardenability. The former refers to hardness potential. The latter refers to have fast steel has to cool to get there. 1095 needs a fast quench. Parks 50 is the only thing I’ve found that gets it right. You can screw around with water/brine and intermittent quenching or whatever else, but Parks 50 and a very thorough quench will probably harden better than anything you can do with water that doesn’t end in cracking.

I have since found “solving” 1095 that it’s tolerant of a little temperature overshot, which probably has to do with having chromium in the alloy. But less tolerant than 26c3. So if you’re going to quench it, heat it past nonmagnetic a little but not too much and not for too long, then quench it as fast as you can and get it to the lowest temperature you can at the end of the quench as fast as possible. For me, this is parks 50 for a couple of seconds and then immediately to cold water after the high heat has been removed, and then into the freezer. This sounds stupid, but I leave a band of frost on the freezer and within about 30 seconds from hot like to stick a plane iron or chisel to the frost in the freezer and then I leave it in the freezer while the tempering toaster oven and the “metal sandwich” that stabilizes temperatures heats.

But….that’s not what’s wrong with it. What’s wrong is two things: 1) there’s nothing really in 1095 that will prevent a soak from getting and leaving a lot of carbon in solution – far more than the eutectic limit. 2) I don’t think the quality of 1095 that’s available now is that great, but some is good. And I’ve been warned by several people that the quality is iffy.

All three sources that I’ve used for bar stock have been different. It’s nice to find someone who lists the alloy, and then purchase whichever source has the highest chromium level. And hope that it’s quality – if it’s not, move on.

What about #1, though? if steel has too much carbon in the lattice, and not in iron or other carbides, the form of martensite is different and it can be filled with small cracks. If you get 1095 just right, it’ll be about as tough as O1. if you don’t, it might be half as tough, and in my experience, that’s enough of a problem to have a chippy plane iron.

I still like it better than 1084 when it’s done right as far as plane irons go. Why? it feels sharper. I can’t think of a real reason to use either 1095 or 1084 for plane irons at this point, though. 80Crv2 makes a better plane iron than 1084 and 1095. But it’s nice to experiment, and if you can really nail 1084 and make it work at high hardness, and the same with 1095, it will improve your accuracy and make heat treatment of other steels better.

Three Tries – Three Different Steels

First, I sent samples to Larrin Thomas without thinking much. I just applied the same heat treatment routine that I would use for O1 and 26c3. I think this causes a little bit of grain growth. Keeping the thermal cycles tighter (right at the point nonmagnetic starts to occur and then let the steel cool) will keep the grain from growing and keeping the temperature overshot lower will keep grain small but beyond just the looks, the result is slightly less hard. My 400F samples were 63.1 hardness and something like 4.3 ft lbs toughness. You’d expect something more like 61/62 and 8-10. Had i tempered them further, I have no clue – maybe they’d have been OK.

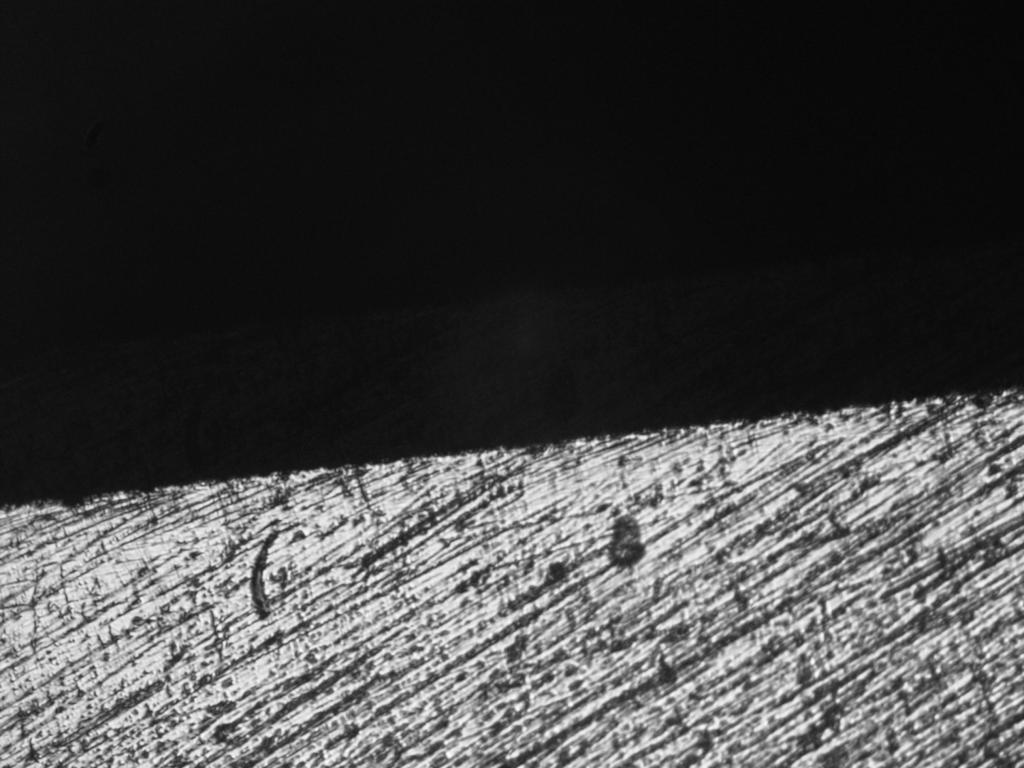

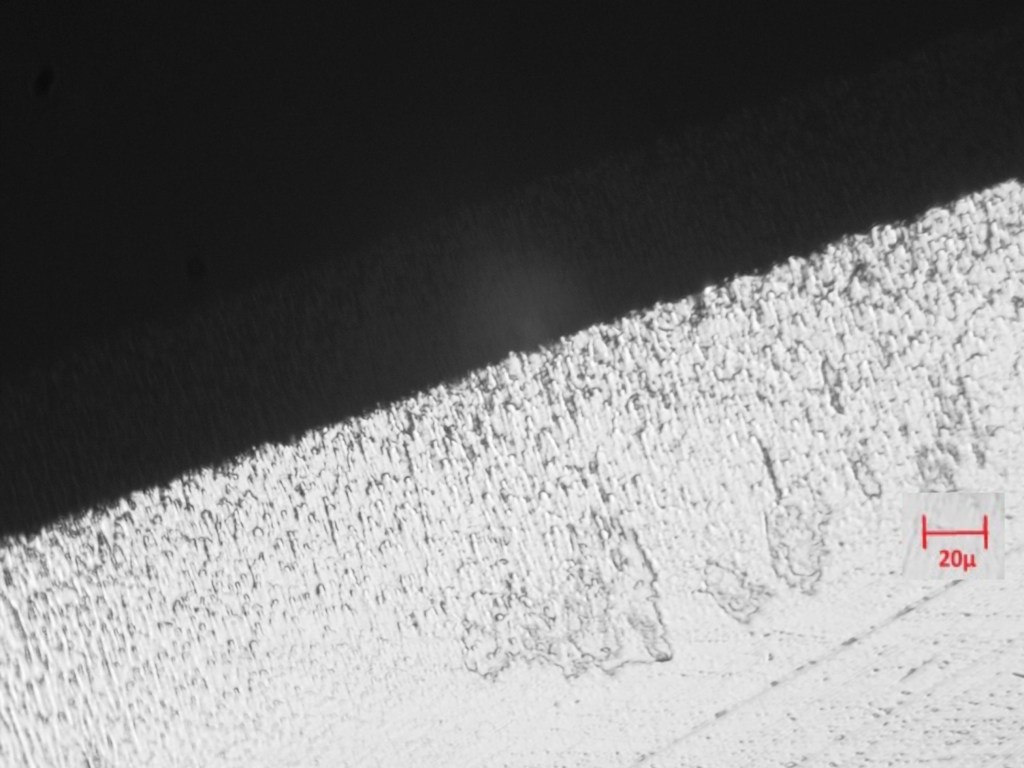

After solving 1084, I did the same with 1095, snapping samples and both observing grain size and seeing how easily they broke untempered. Steel should break easily when hit with a hammer untempered, but there are alloys that retain austenite at a high % that would prove that wrong. None of the plan steels that I’ve tried will resist breaking though. Breaking tempered steel would be more accurate in terms of actual usable toughness, but high toughness steels can become really hard to break so I don’t do it – the grain is the focus.

The first 1095 that I bought was from New Jersey Steel Baron. Since I didn’t have Parks 50 at the time, I was kind of unimpressed by it. It was also very cheap, so I didn’t care that much and put it aside. fast forward to now and I like the version that New Jersey Steel Baron sells. I try to avoid anything that would resemble a soak to maximize the amount of carbon in carbides. I do this with a pre-quench and then a sort-of anneal in vermiculte, and then do as much as possible to not go past nonmagnetic for thermal cycles before quenching.

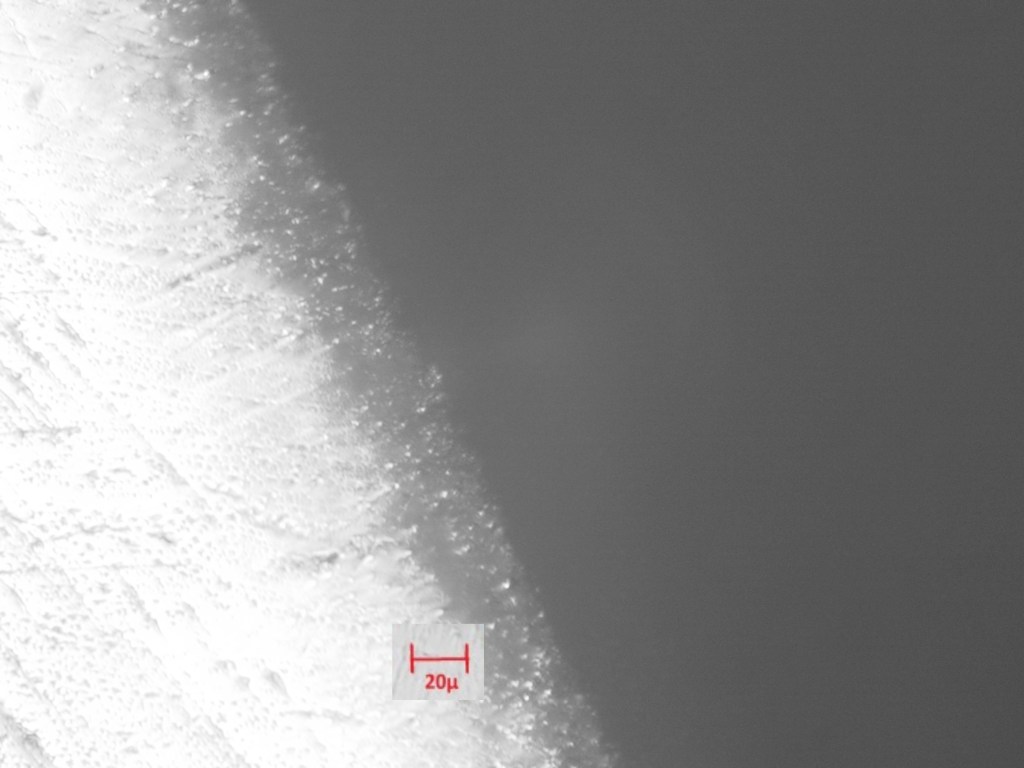

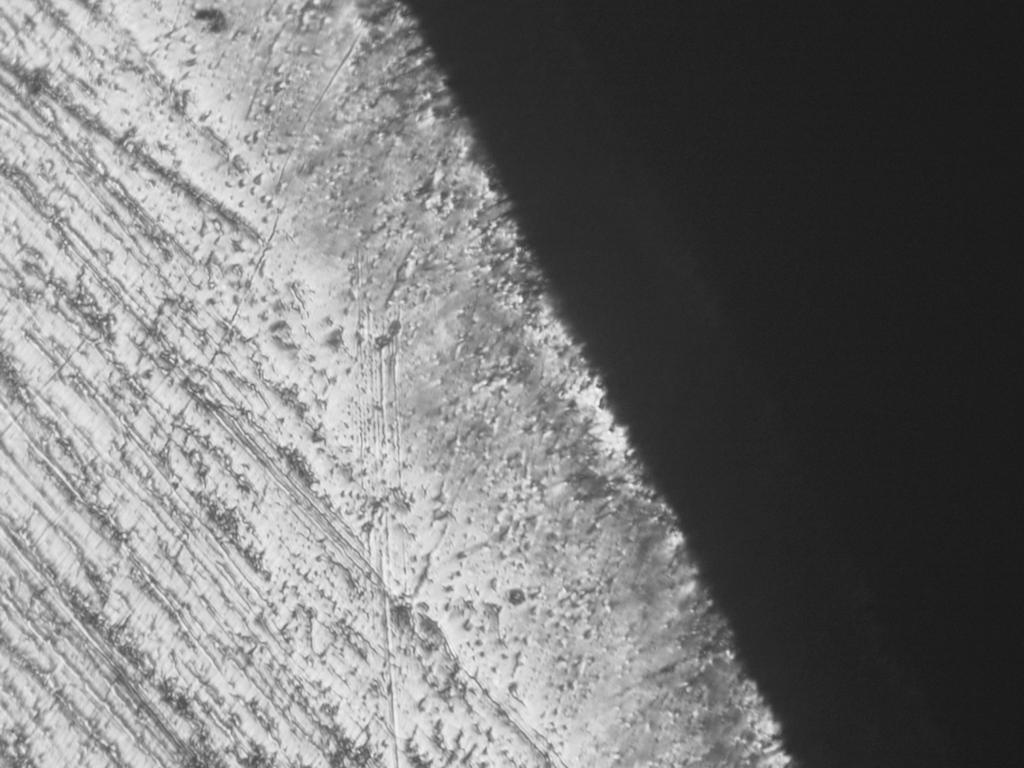

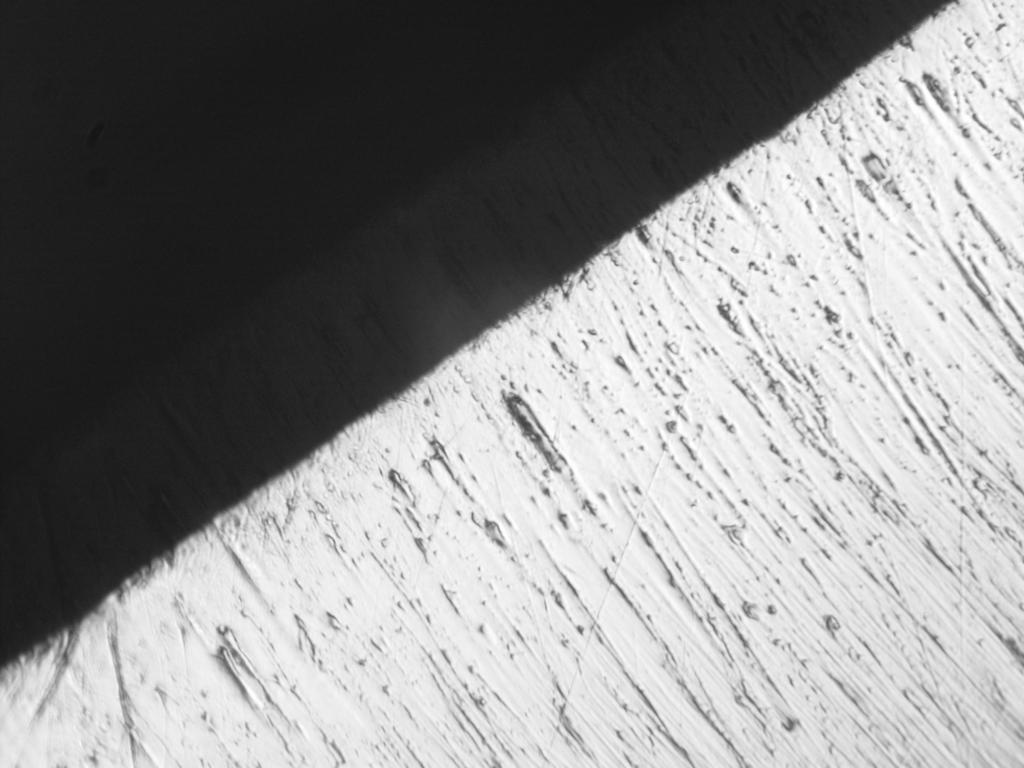

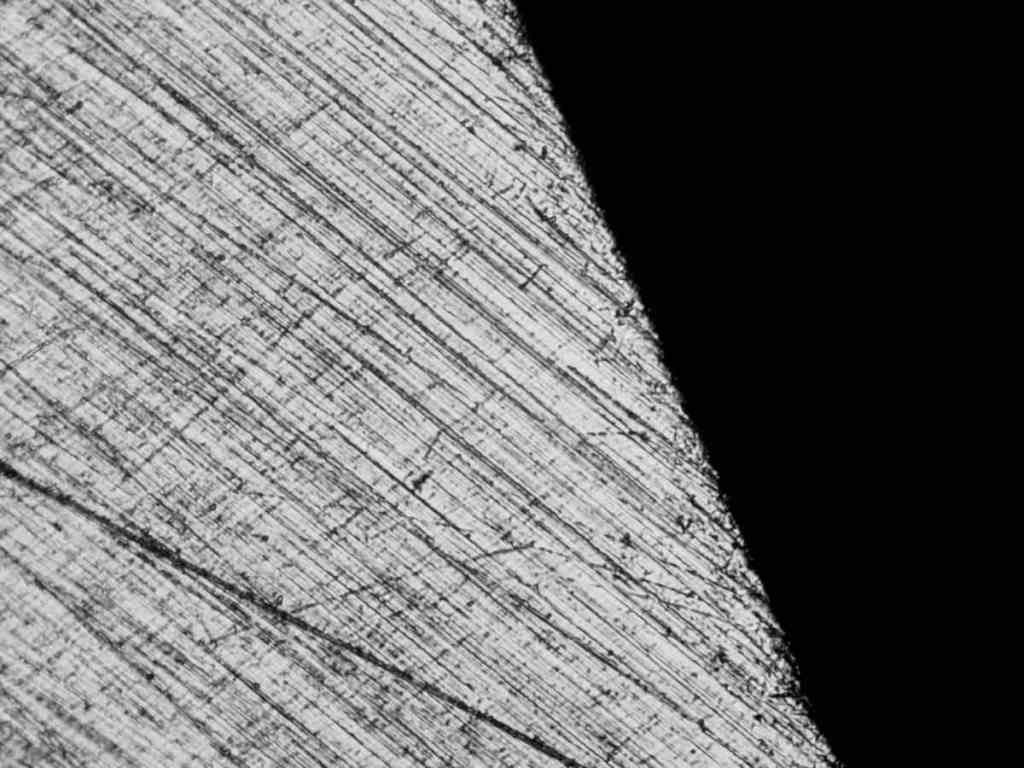

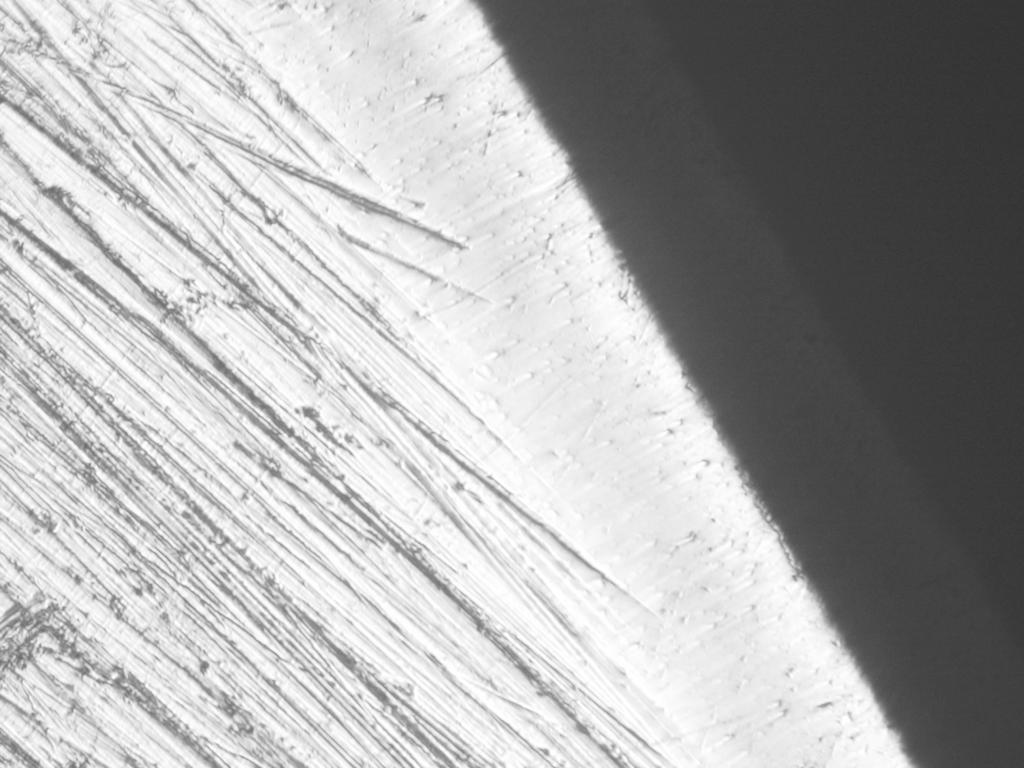

Still, the result isn’t exactly a cornucopia of carbides and I haven’t found the free lunch. But the early samples that I made showed almost no carbide and I’ve gotten to this point. The iron may be a point softer, but the edge holds up. And the straightness of the edge is wonderful. This uniformity seems to be important along with an edge that doesn’t look very rounded right at the tip (AEB-L, for example, wears longer, but the edge shows a more rounded profile – I don’t know why this is).

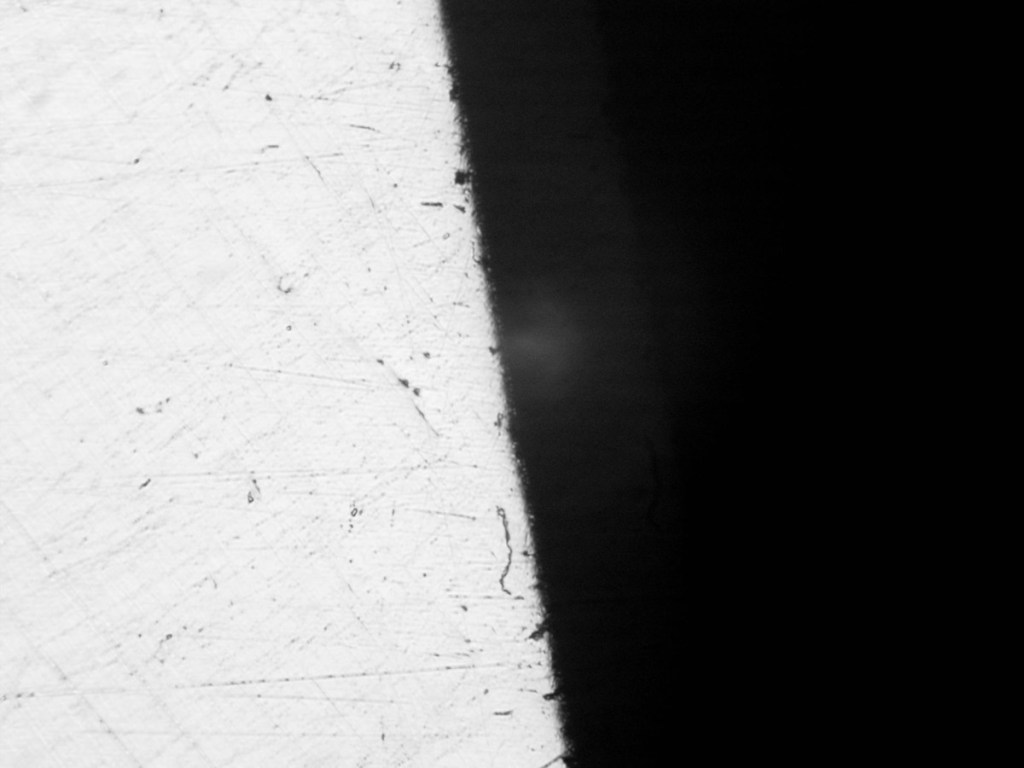

The second 1095 that I bought was from Alpha Knife Supply, which is where I get 26c3 (love it for chisels, obviously). The listing doesn’t reveal the mill but mentions that if you want great quality, finding bohler or ordering a melt from bohler is safe – or something to that effect. So, it’s probably not bohler, or the listing would say. This 1095 seems to have some oddness in it – not terminal by any means, but the shiny spots in it look like something that wasn’t fully dissolved, and I didn’t normalize the steel or do anything unusual, it’s just bar stock, so I think this is how it arrived. This bright spot wears just a little slower and leaves a stripe on wood that can be seen but not felt.

The AKS sample here is actually the first one I got right, and I puzzled about the stripes in use until getting the blade under the microscope. If the iron isn’t very good, there will be defects, anyway, so you don’t know right away if you did something wrong or if it’s the steel. It’s *rarely* something in the steel.

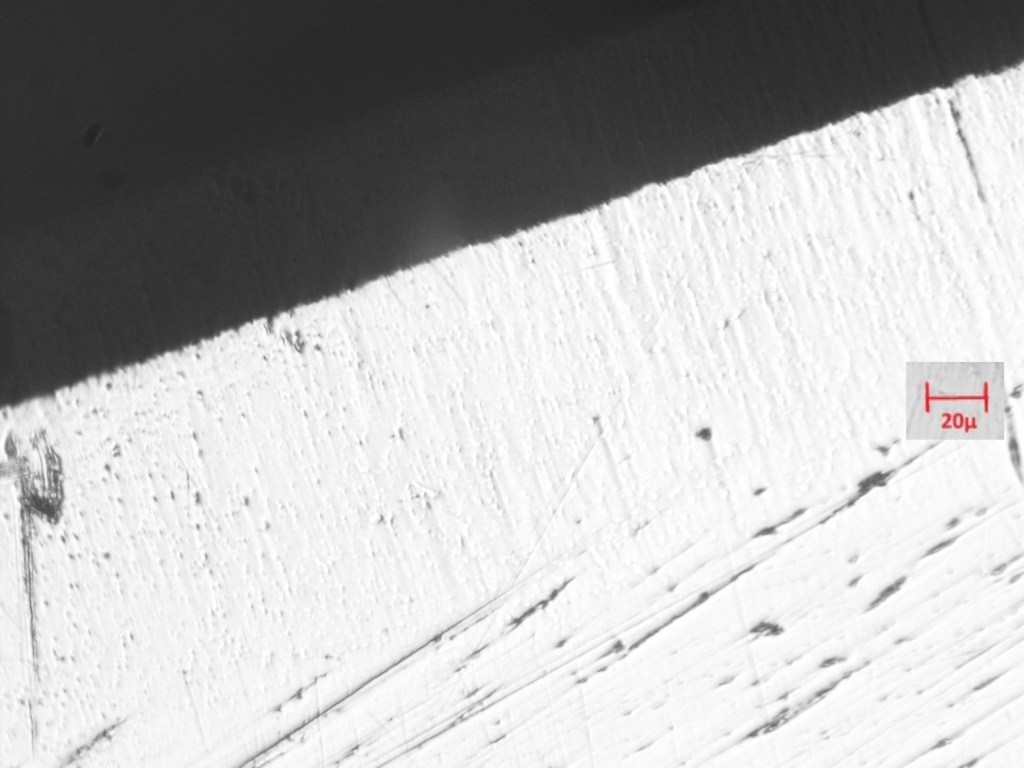

In an effort to find 1095 with more chromium, or more like an an observation while browsing for other steels, I found that USA knife maker had a listing with chromium near the upper end of the spec range and also had added nickel. The results of that are also good, just as the NJSB version. There’s no guarantee that some of the vendors aren’t selling wholesale to each other or selling from the same wholesale source, so the first and third pictures could be the same stuff just from different sellers.

I don’t see much there, but will take another shot at wearing one of these irons. it seems the key to getting a really robust view of the carbides has to do with setting the cap iron closer and wearing more deeply in to the back of the iron.

nonetheless, this iron seems to work well.

I haven’t done any roughing of wood lately so I don’t know if toughness will be an issue. These irons subjectively wear a little less long than 80CrV2 or O1, but not too much less. the edge quality is nice and they feel more crisp than 1084.

But I also can’t think of a practical advantage to continue to make or use them. It’s just nice to get them right.

1095, like 1084, is cheap. if it costs more than $7 of bar stock to make an iron, I’d be surprised.

I sure would love to get a hold of the Sharon 50-100B (I only have the version without vanadium) or Carbon V or whatever Kabar is currently using to make knives. I get the sense that the extra chromium and the vanadium do the same favors they do in 80CrV2 and the toughness would be greatly improved enough to maybe be worth using that steel in chisels as well as plane irons.