(Click here for the summary version)

If you peruse ebay or aliexpress or possibly youtube, you’ll see some of the stones offered from China. There are a few that are unique (agate, the gray slate stones distributed usually to shaving enthusiasts, etc).

One that’s stood out to me but I’ve been selectively too cheap to buy is the ruby alumina stone. By rating, it’s sort of an in between stone, and it appears to be just abrasive either in almost nothing for a matrix or in nothing at all (fused or sintered?).

The reason I drag my feet on these is that I just don’t need another stone that’s about 40-50 bucks that just goes in the drawer.

At some point, I decided otherwise, and since aliexpress lets you sign in 99 different ways, I have no idea what I logged in through to make the order, so I couldn’t tell you the cost. But I can tell you it wasn’t 40 or 50 bucks because I ordered a 2×8 version of this stone that is combination.

If you’re ever on the fence about something expensive, like a dan’s black or translucent, or anything where the stone by commodity/availability just isn’t going to be cheap, ordering a combo is a good way to cut the cost. I mention the arkansas stones with this because something that is really hard is also something you’ll never get through a 10th of even half of the thickness of the stone. So this stone was probably about 25 or 30 bucks.

I chided myself a little bit for buying it even at that as I’m trying to get over a very long time habit of buying things out of curiosity (rather than need).

The other reason I dragged my feet on this is, I guess, several reasons. I have three white fused alumina japanese “barber hones” that are actually a little bit too fine. They are what you’d want from spyderco if you had a choice, though – giant 8x3x1 ceramic. And they work. I’ve also got a few nifty ultra ultra fine india stones from japan, which is something I wish was sold here. They’re a freehanders delight. Why? the explanation is something I learned with razors – if you want an ultra fine edge, the last step should install it and not try to do two. Typically, I would hone with two stones and then buff strop (just light work on the buffer, not the whole unicorn thing) when sharpening plane irons. You’ll see pictures in a second as to why the stropping still (it’s five seconds, not arduous). At some point, how long before I grind is defined by how fast the second stone is – everything ties together – I’ll stop there or this will be 10 pages of combinations of stones that I think work nicely for freehanding.

The point of that bit about speed, though is if you really go very fine, it should be 10 or 15 seconds of something that’s so fine you couldn’t expect it to follow a second hone. In razors, a fallacy is the idea of some really fast stone that will be ultra fine and pass this test with proof under a microscope. No such thing exists, and attempts at getting close to it are super expensive without being the best option. when I sold some japanese stones that I’d fished from japan, I found that very fine slow stones (but not junk, good stones, just extremely fine) did well finishing a razor, but they did well when paired with a stone that’s not quite fine enough. The result is that the pair works faster than the “it” stones, the edge is better, and the cost of two stones that aren’t “it” stones is often about 1/4th the cost of an it stone. It’s about getting results more than it is having the perfect stone.

Phew

I did it again, grew a tangent tree.

The above drawn out stuff is a slow way of getting to thinking that maybe because these (ruby) stones are labeled as 3000 grit that maybe they are an in between stone. What I’m really fond of is stones that finish edges fast, but aren’t quite coarse enough to raise a burr on good steel, and that can be followed by little buffing but still improved by the buffer. That gives you the option of very crisp sharp edge, or you can go full unicorn if there’s a need (chisels, planing nasty wood…).

Grit is a funny thing in china. You may see an agate stone that is too fine and slow to do anything, and it will be labeled 1500 or 2000, and then someone else will call it 12000. A stone that’s a little too coarse for me is no good, though.

It turns out that the stone is actually on the very fine side, but not quite as fine as a good hard (trans/black) ark. A picture of the 2×8″ combination stone follows:

Weird color, huh? It’s likely just the color of the type of alumina used. The bottom side is also relatively fine, about like a medium spyderco, and it’s described as “boron carbide”. I haven’t used it. I don’t care for combination stones other than the money saving trick because anything sticks to the bottom and are you really going to clean sides of the stones off every time you sharpen? No.

This stone follows an india stone nicely, and hopefully it won’t get any finer. Having made two W2 irons that are of pretty good hardness (probably 62), it seemed like a good time to compare this to a cheap hard ark with diamonds, as there’s nothing at all in W2 that alumina will not cut.

The burr from the india stone came off, and with minor teasing of the edge, little of anything was left. A picture of what this looks like will follow, as will a subsequent point about buffing (or stropping if you’d rather strop).

And one other side comment – a warning. I have no clue if all of the vendors of these stones are selling the same thing, or if they vary.

But in estimating the fineness of this stone, I would say it’s more similar to a 6k grit stone, and from experience, if the alumina is truly fixed, it will dull and slow down, and if it does, I will adjust it with a worn out diamond hone. I already have really fine slow stones.

Edge Pictures

I was on a multi-faceted mission and not thinking of posting about this stone. That mission included gathering feel data about the W2 irons to see how similar they were as I heated one a bit higher than the other before the quench (on purpose) to see if there would be a hardness difference. There is a little – maybe a point. I also realized, and the reason for busting this out, that when making harder irons, the arkansas stones are a long term edge refresher. They’re a little lacking for getting everything in order after working over the backs of tools and then needing a couple of sharpening cycles to get everything good all the way to the edge. I’m trying to get from a house made iron to “can’t be improved” in five minutes, so the exercise isn’t like a half hour session when you buy a new already flattened chisel and follow a video procedure for half an hour. I have no problem with that, but it’s not a good match for making several things a week where one or two might have some minor warp issues to grind out and then hone.

So, the first picture isn’t actually proof of anything but being a good match for one single pass across the buffer, as I just sharpened one of the two irons to see how it would come out in a day to day 1 minute honing cycle.

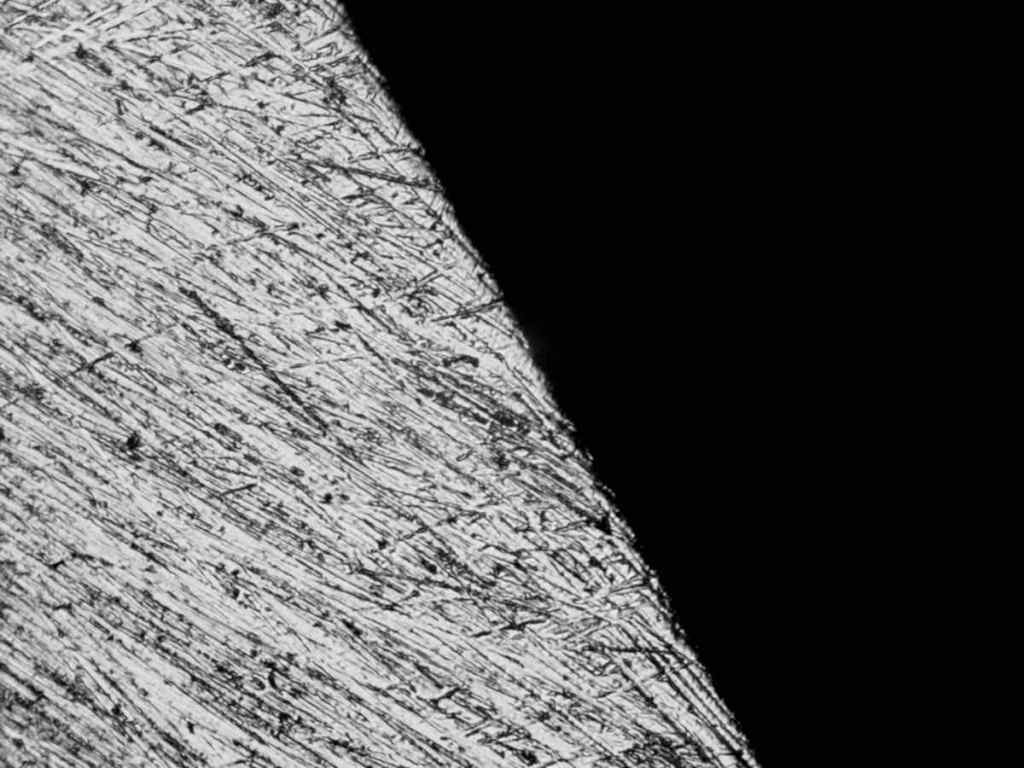

This picture shows something that’s really in line with what I wanted. There’s no rounding of the edge, and the edge itself is straight and thin. it doesn’t, of course, look like a 0.5 micron oxide edge (that would just be plain white), but it’s quick.

To compare the edge uniformity to another standard option, you can see the 8k kitayama waterstone edge here. They look similar, except this quick edge isn’t rounded over by rolling slurry. It’s sharper, and certainly much faster and less fiddly.

A shaving from the harder of the two W2 irons, from cherry:

That’s pretty good. The shaving is thin enough to not even bother with stretching it over the writing. I’d guess somewhere around 3 or 4 ten thousandths as that always seems to be about what I can get with something that has a good thin crisp edge.

Excellent – pleasing both with uniformity of the edge from the iron itself, and from the ability to go quickly from a fine india stone to the ruby stone to five seconds passing the iron in one swipe on each side across the buffer.

But the question arises of how much of the picture is the work of the buffer and how much is the stone. It should all be the buffer as I never work the back of a stone in a direction such that the perpendicular lines will be created.

That is the work of the ruby stone itself. When you get away from something approaching a full polish, it becomes difficult to tell how fine it actually is. The important thing for me is I don’t ever use anything without stropping in some way because the results aren’t consistent enough and I find it annoying. You could plane with this without issue, but it would probably lose about 25% of the edge life vs. the quick buffed edge. Interestingly, if I keep buffing the edge to refine how it looks and make the bevel side more uniform, it would be a good edge, but also lose some life unless something in the wood demanded the rounded edge. Finish planing or try planing clean wood usually doesn’t.

Most importantly, you can see that even though I teased the burr off, there’s little remnants of it. If I leather stropped this, the appearance of everything but the edge wouldn’t change much, but the uniformity of the initial edge would be better as the false bits of jetsam would be taken away. When defects are larger, they actually can propagate in steels that are too tough. I really don’t know if you just plane this stuff off if it makes that much of a difference, but that’s a false dilemma, because we can buff the junk off and refine the edge in five seconds.

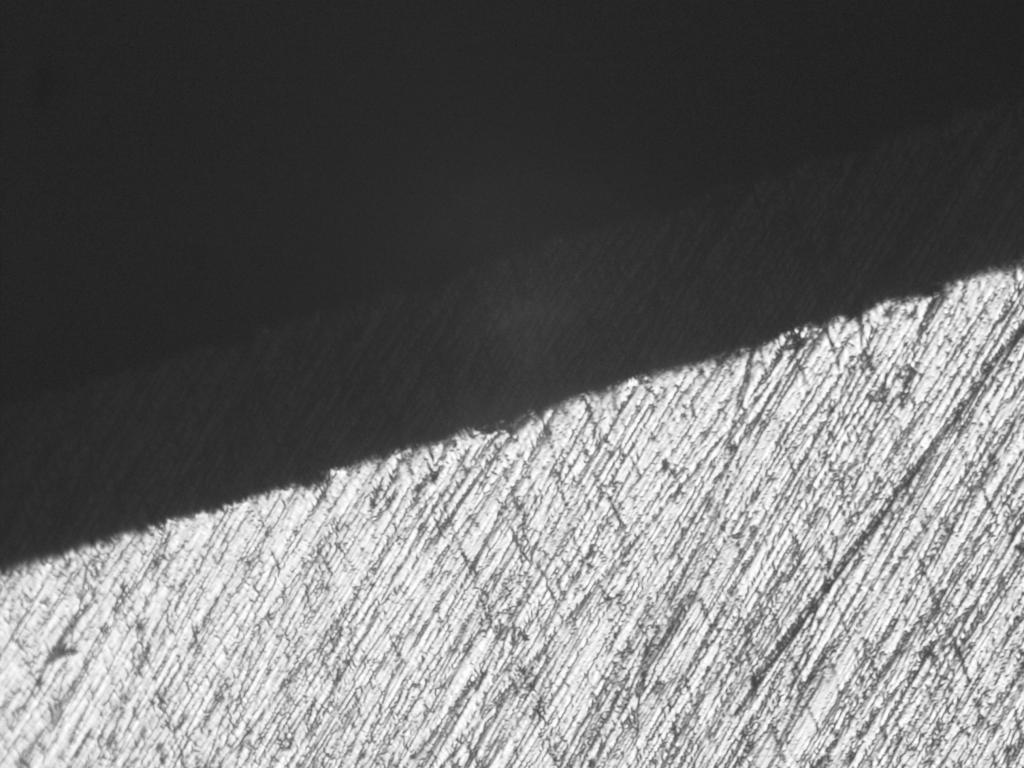

The second picture here is the second W2 iron – not the same iron as the first picture. So I buffed this one even a little less long to see what the edge would look like. This last picture and the picture of the unrefined edge are the same edge. If you’re gauging how much buffing, I would say firm across the back of this iron nearly tangent to the buffer and one pass that takes about one second. And then the bevel side across the corner of the wheel (softer, less honing or rounding). Less than five seconds, I guess.

Less buffing and some original scratches remain. The ones that do could actually be from something laying on the stone or they could (different iron than the first) some remaining scratches left by the original flattening on an india stone.

The shaving from this effort looks like this:

No reason to bother stretching the shaving out for more wow factor on the picture. It would be uncommon to chase shavings like this in work, even on the finest smoothing. The wood doesn’t usually demand it. They describe a lot about the process and the capability of the iron, though.

And as there are a few stray marks left on the second iron, what the real aim is is getting to the point that the back work is just done on the red stone with no remaining stray marks, and with an iron that has enough edge stability to never really need anything more coarse on the back side. Sharpening becomes then a 1 minute process in the rhythm of work.

And I think there was probably a lot of historical practice of this idea 200 years ago when the work was fine work. The beginner’s concept of variation in what’s happening or stopping to “grind out nicks” or whatever else would’ve been intolerable pretty quickly.

Conclusion for the stone

What I was hoping with this stone was a lucky match – something that would work pretty quickly getting all of the bevel side work out at the tip from the fine india, faster than a trans ark, for example, would do. That’s achieved. Also, fine enough that significant buffing isn’t needed if desired. That’s achieved.

Would we find some magic property where it was much faster but also super fine on its own without the buffer? No. So if you see one of these and consider it a replacement for autosol or a very slow fine stone, it’s not that.

I like it enough that I’m going to make a box for it and use it, though. It’s as fast as the mid (next to finest) arkansas stones, not messy, more tolerant of chasing slightly higher hardness in plane irons and chisels, and it’s harder and should wear more slowly. Everything in the shop has to have a box – that might be different for you. I have ambient metal dust floating everywhere, and even the finest of it or even wood dust would destroy the edge shown in the picture. Not because the wood is harder than the metal, but because when the iron goes over it, the edge can be deflected.