OK – there’s been some delay in getting this wrapped up. I finished the chisel, but the chisel is a different chisel. The first two parts are unchanged, but charging forward and trying to find something to make a single piece chisel including integral bolster just happened by chance to run into trying a steel that is defective. The 115crv3 bar that I was using is defective. I relayed my experience to the supplier of the steel and they gave me a refund and canceled a back order that I had out there. Phew. So, I went back to W1 bar, and the last post here is a chisel made from W1.

This process changes none for any steel that I use other than the heat treatment, and I think it’s not worth going into specifics about heat treatment.

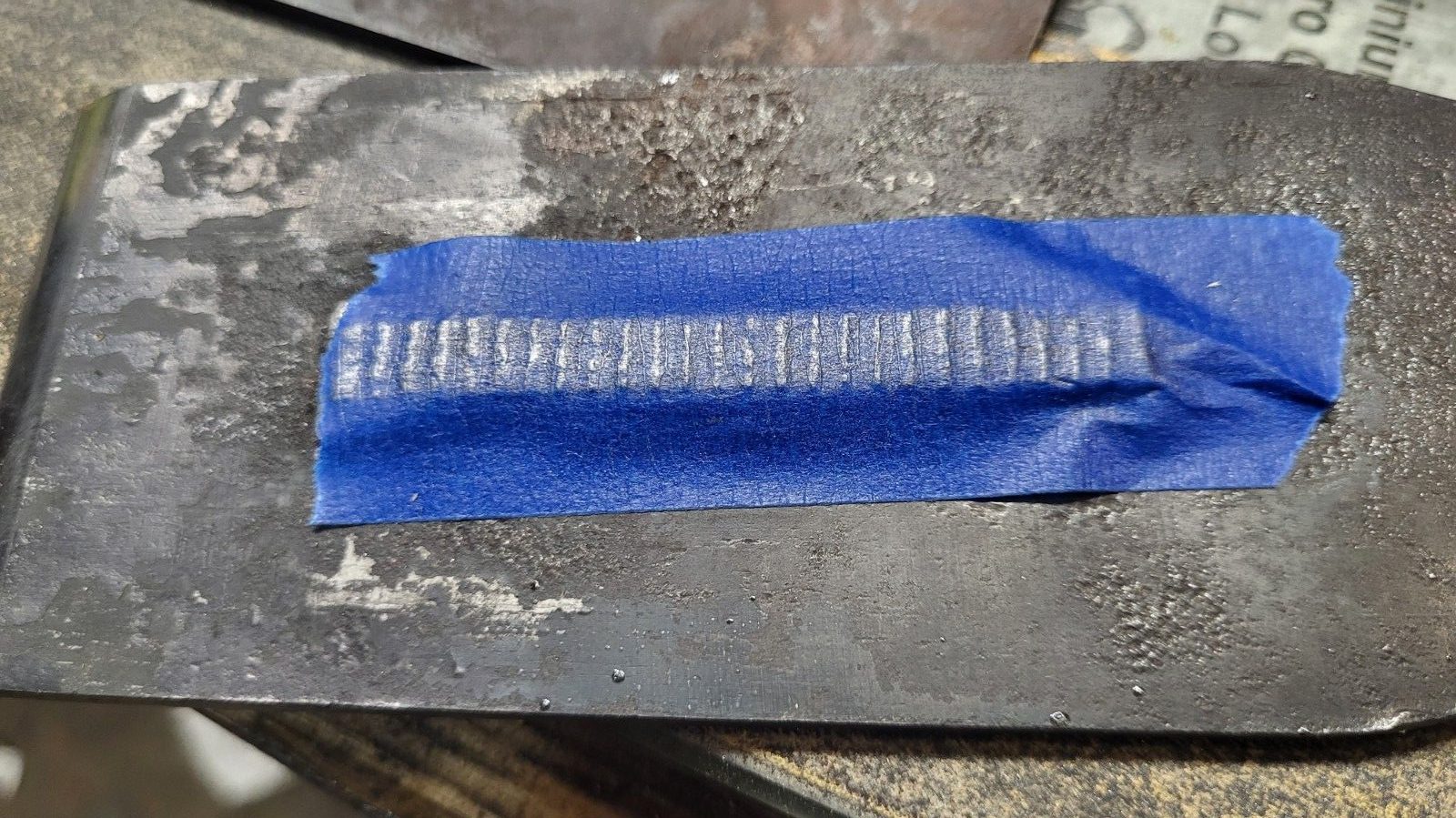

The W1 replacement looks the same – but I forgot to take a picture of it flat out of heat treatment. I thought this was the chisel, but this is yet another one after, but pretend it’s the W1 chisel. Flat and wedge shaped in profile as far as thickness goes:

I do almost all of the shaping and finishing work on less than precise grinders because none of it is jigged.

Actually, you can see the three things I use. Any of them could do all of the work. For example, on the left is a simple “bucktool” 4×36 sander. That brand is a low cost direct drive brand that you can find on amazon, but the sanders are not all the same. this one has a steel platen bed with some rigidity and a graphite coating that’s infused into woven cloth. it’s the best graphite platen material I’ve seen in terms of durability.

You need a sort of flat area somewhere on something, and an idler.

Which brings up the two grinders. One is back right. the spindle sander is for electric guitars, so you can ignore it.

Both grinders are identical, and they have the cheap multitool attachments. one is 4×48 and the other is 2×48 with a larger contact wheel. The two separate sets of units are some fraction of the cost of a “good” 2×72 grinder. The multitool attachments are not high quality or precise, but I haven’t broken either of them. So there’s a lukewarm endorsement.

The grinders are the Jet IBG-1, which is only important if you consider the power level important. They’re hogs for an 8″ grinder (11.5 amps and strong), which makes them a good candidate. Unfortunately, Jet has decided to almost double the price of them in the last two years at street level (they were $260 each when I got them, and now $470 seems to be the norm). I’m sure there was a “shortage” vs. just money grabbing. Or maybe they’re in the club George Carlin talks about and we’re not. Whatever the case….

I figured I’d show what I use – I’ve made entire chisels just with the 4×36 belt sander and if I did it here, you wouldn’t see an aesthetic difference. It would requirement to hand file the neck/tang area of the chisel, which I did for a long time. To put that in context – forge welding the bolster was later, so you could profile the tang mostly with the idler, weld on the bolster and then hand file to clean up. The bolster is now there out of forging so I do the rough grinding with the wheel. The wheel is 24 grit. Strangely, despite alumina prices being about the same as they were two years ago, these have also increased 72% in price. and when you do heavy grinding, you will actually see consumption of wheels that you’d never have considered before. One because you’re doing lean in grinding and two, the metal up to the point of the picture above is unhardened.

But that’s the past – we heat treated now, and heat treatment should leave the tang below the bolster semi-hardened so that it can be filed. The tang after the bolster inside the handle is unhardened.

Phew, a lot of background here – but it will feed into the discussion forward. I think you do not want to consider trying to jig anything you don’t need to jig. It’s limiting to do that and then the work is also boring.

On to the Finish Grinding and Bevels

The chisel is generally still wedge shaped and not warpy at this point, but if there is a slight lateral warp, observe it so that you don’t forget about it. Visual warps can be a matter of a couple of thousandths and they’re seconds of work to deal with. I leave chisels ever so slightly wide if the width really matters down to a couple of thousandths and then grind the sides to width after heat treat so that they’re straight with a very slight width taper. it makes for a nicer chisel to use than parallel sides.

At this point, I will grind the top curvature into the chisel. that is, the bottom is flat, the top shoulder is thick and the first several inches of the chisel are thinner, so the natural solution to this is some curvature in the taper as you approach the shoulder. It again makes a better chisel, but it also looks more interesting – a nice combination. On a short radius contact wheel it would seem hard to do this because you can create a lumpy surface. Working in slight diagonals both ways will eliminate most of this and if you see a spot that needs more ground off, of course you just do it by eye until it looks about right.

I don’t have a picture of grinding the bevels, but the biggest reason I got a picture of the idler wheel at the end of the belt on the Jet grinder is that is where I grind the bevels on a chisel.

Linearly. As in, I feed the chisel straight up and down with the length of the chisel in the direction the belt travels, not across the idler wheel’s width. That decreases the contact area and slows the process down.

It takes about five minutes to grind both bevels with a coarse belt, and to do it reasonably neatly. If you could do it in 15 seconds per side, it would be hard to do accurately. There is a dip bucket below the idler both to catch swarf and lower the amount of dust in the air. A couple of passes with the contact idler and into the bucket the chisel goes, but it never gets hot enough anywhere that I can’t touch it. This small point of contact on the idler with coarse grit is important – we don’t want to just not exceed 400F, we don’t want to get close to it. Once the bevels are on, heat treat isn’t a reasonable option with a water hardening steel.

Make yourself a routine. Three times up and down the contact wheel, dip in the water, look. I do both sides of the chisel progressively so that I can look down at the bevels, at the sides, and then from the front. There is no jig, so they are even by eye.

Once the bevels are on, I do the same thing with a finer belt, and then into the vise.

The chisel is held by aluminum soft jaws and I work over the ground surfaces with a sanding block with 180 or 220 grit paper until all of the machine marks are gone and any lumpiness. You can adjust lines here a little bit. The perspective makes the bevels look uneven, but they’re not.

This is the actual W1 chisel, of course. I cross file the tang both on the sides and below the bolster and lightly file off anything black on the bolster and then clean it up. The order of all of these things doesn’t matter that much, they just have to get done.

Somewhere on youtube, I have a video of cutting the final bevel on the chisel using a spray bottle and a belt sander. it takes about one or two minutes to fully cut a long shallow cutting bevel after this and do it without heating the edge. you can intermittently grind on a very coarse ceramic belt and dip often and check temperatures with your fingers, but I find a slightly finer belt and a light spray of water just dandy.

You can use a flat belt on glass or a rotary diamond plate or something to finish flattening the back of the chisel – I should mention that I often do that before adding the finished bevels for several reasons, but you’ll figure that out. At the very least, you don’t want to overheat thin edges. I started using 10″ rotary diamond plates to do the final flattening of backs post heat treat because of trouble with a heavy hand on the long sandpaper lap, blistering fingers with heat and at least once, drawing temper by accident. The lap that I use is just a $30 10 inch diamond lap off of aliexpress glued to MDF and fitted to a mandrel for the drill press (low speed, too!! High speed grinding with diamonds is a no no).

After handling the chisel, this is the result:

The handle is oiled at this point, but varnished later. Since this is the first W1 chisel of this type of make, I was hyper to see how it would hold up malleting a couple of cubic inches of maple. It did fine. I think 26c3 is a step better for harder woods, but it’s not available.

Even as I look at this picture, the tang is too long. but that’s a known thing – my grinder wheels are 8×1. I have a narrower wheel coming in the mail to do the early rough grinding and bring the shoulders up closer to the bolster. the tang is plenty heavy, though – it’s just an aesthetic issue for now.

Amber varnish on the handle brings us to a close. Shellac and oil would also be fine, or whatever else you’d prefer.  .

.

I didn’t discuss how I make the handle. It’s separate from the chisel and it’s just a handle with the socket hole step drilled freehand. How do you get drills that like to wander to make a hole in line with the handle? Freehand. you drill a little and adjust the direction of the drill as you’re going so that the handle spins without much runout. You’re looking at the drill that drills the handle in the background. I’ve got no tolerance for trying to jig something like this up – it’s lazy, time consuming and the result is often worse. We are makers, and can trust our hands and eyes.

.

.