I often toss around the trade names for alloys (can’t keep track of the brands that try to hide – if you recall yesterday’s discussion of W2, there are something like 30 trade brands for the same thing).

But what I don’t have is my thoughts on steels that I have experience with, so you can reference them if you’re the rare person who comes across this blog and want to know basic characteristics.

I think it may be a good idea to put a summary of characteristics for each, and some description. There are descriptions of steels all over the place, but they are not commonly described in a woodworking context, and when they are, often by ad copy and lacking accuracy or tangible meaning.

Characteristics of O1

(characteristics are not for high speed turning or drilling)

Reasonable Hardness Range: 59-64c. Sweet Spot: 62c

Toughness: At the lower end of suitable (but still suitable – only a problem if heat treatment is poor).

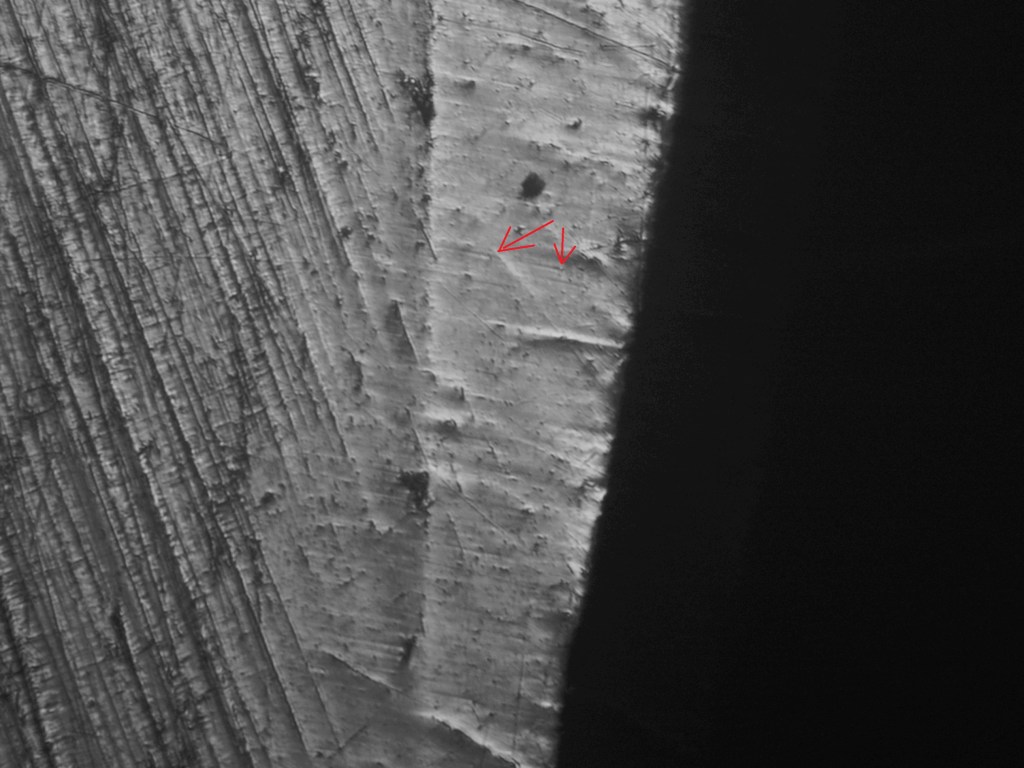

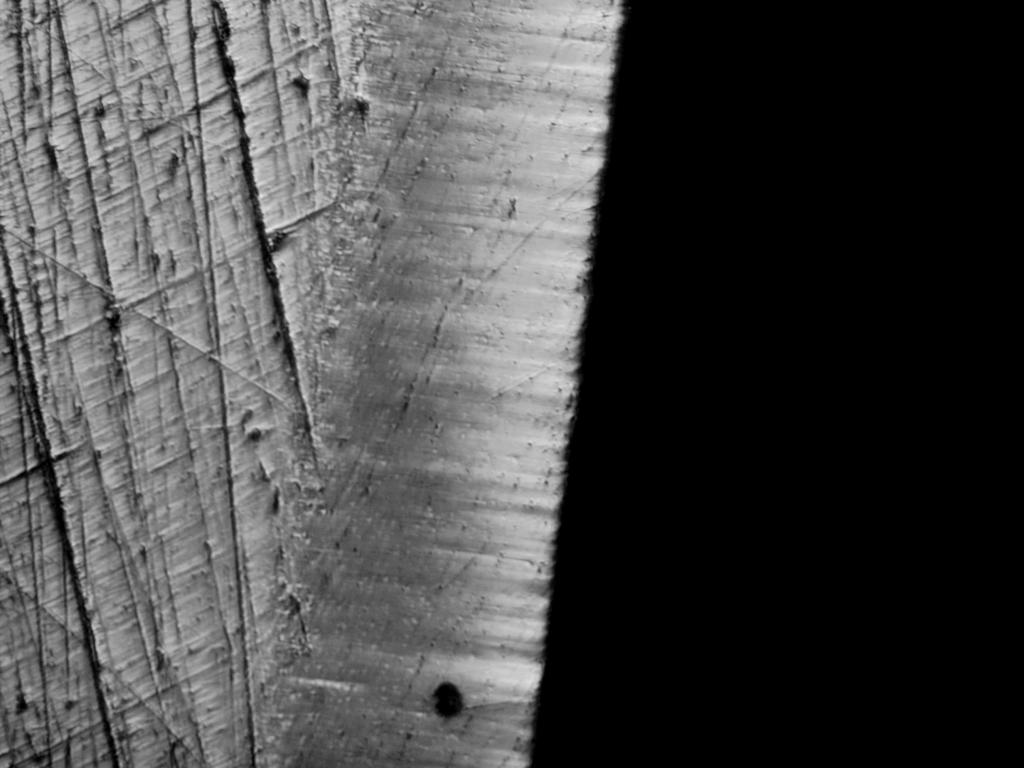

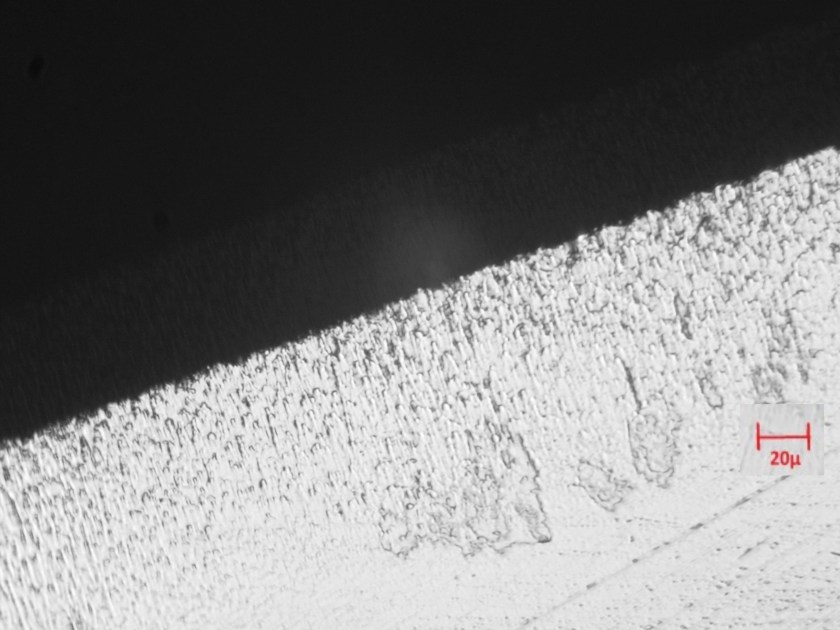

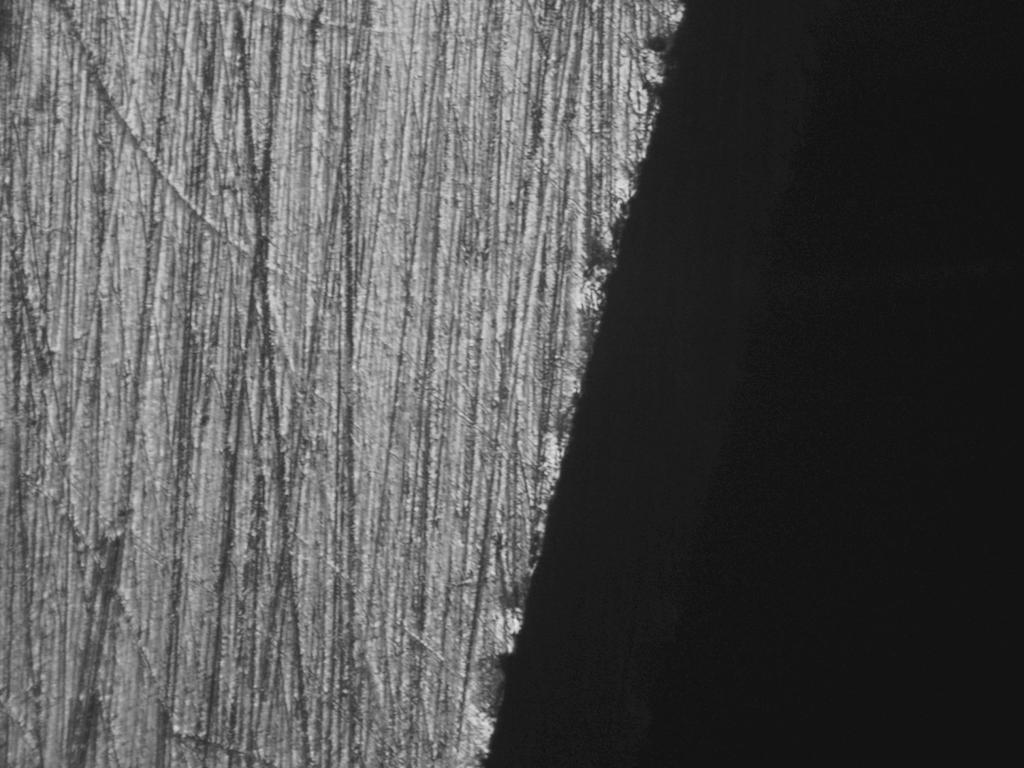

Edge Fineness: Very good (fine carbides in the 1-2 micron range, evenly dispersed)

Edge Stability/Keenness While Dulling: Good – stable edge fineness for anything but fine razors. Retains good sweetness while dulling during planing (smoothly picks up shavings and retains uniform edge until sharpening is needed to remove wear)

Wear Resistance: Good. We’ll use 62 hardness O1 as the bar going forward as no skilled woodworker would be dissatisfied with edge life at that hardness, though amateurs may perceive they should be. That’s a different problem.

Elimination of Defects in Routine Sharpening: Good with good heat treatment. A skilled user is unlikely to need to “stop and grind nicks” before an edge is dull.

Brief History

O1 is a relatively modern (for steel) follow-on to water hardening steel. It’s more hardenable, meaning that it has more additives that are required to harden steel (manganese, and chromium notably) with chromium doing something positive in small amounts with iron carbides according to Larrin Thomas. The composition of the steel in general will be provided at the end of this article. My thoughts are generally that you can feel the alloying in O1 if you get used to water hardening steel. it’s “slick” feeling on stones at same hardness, but not nearly so much as something like A2.

The through hardening (= the entire cross section of a tool being hard through and through rather than just in a surface layer) and relatively easy machining makes it ideal for some die making and machine shops, so I think we will not see it disappear from woodworking use, but it certainly wasn’t developed for woodworking. Actually, I’m not aware of any steel that was ever developed for woodworking – we’re a small market and we use what’s available.

Increasing Manganese for hardenability wasn’t really an original idea. In the 1800s, an early type of air hardening high speed steel was discovered or developed (Mushet steel – you can look it up). As far as I know, Mushet relied on a lot of manganese (double or more that found in O1, ten times or more vs. some fast quench water hardening steel). Too much and steel is brittle – the fact that we’re not using Mushet steel probably has to do with brittleness or cracking because it’s possible for steel to be so easily hardenable that in open air, it would cool too fast to be stable.

What happens in general for us (this always depends on what you’re comparing O1 to), the alloying improves wear resistance (increased hand plane life vs. water hardening) over very plain water hardening steels. The overall effect of the additives leads to strangely uniform small carbides given the amount of alloying, too. In terms of the reduced toughness, there is still enough for woodworking. That’s important – the world of all purpose knives and boutique knife makers where a lot of robust steel discussion occurs…..very fascinated with toughness. People return knives they break. We typically don’t break tools made of O1 because we’re not prying in tree stumps to make a youtube bugout camping video. What we like is strength and stability of the very tip of an edge that’s in the wood severing fibers, and O1 is relatively good for both of those.

Commercial Availability in Woodworking Tools

O1 is relatively common in boutique tools. some variation of it may be in older tools, but most European tools that don’t mention the type of steel or mention Chrome Vanadium are generally not O1. If a manufacturer uses the alloy, they usually mention it as use probably was uncommon in thinner cross sections (plane irons) until the last several decades.

Iles makes good chisels in O1 that seem like they’re right in the sweet spot, though I’ve had a set of boxwood handle chisels that were a bit soft. LV offers an array of irons that are a bit underhard to be as good as they could be in my opinion, and Hock tools offers tools that are on the other end of the usable range. There can be reasons for both of these – but it’s my opinion that a typical user would prefer something done between the two.

For Hobby Toolmakers

Not a great steel for forging, but there’s little that a hobby toolmaker should be done that involves any of that. Leave that to people making reproduction lock sets and starring on cheesy TV shows. Bar stock from good retailers or known mills (Starrett as a brand, Precision Steel (brand), Bohler (mill), etc – ever so slightly different in composition but all good).

Stability in hardening is middle of the road but far more stable than the most unruly of water hardening steels, and just generally heating to nonmagnetic and then some past that (quickly, like seconds, not minutes) results in good tools that will match commercial offerings.

No special oils required to quench due to the additives. And easy to grind, drill, file, shape with only moderate air hardening if heated to red heat while working.

Typical Composition:

Carbon: At retail, usually 0.9%-0.95%

Manganese: 1.2% (you’ll find out that vs. plain steels, this is a lot)

Chromium : 0.5%

Tungsten: 0.5%

Silicon: 0.3%

Vanadium: Up to 0.3% (but in US retailer offerings, usually not included).

These are what I’ve seen from easy-to-find retail sources, and not necessarily a full industrial spec (range may be wider).

Sites like Knifesteelnerds.com have more information on the history, and the owner (Larrin, a “real” expert metallurgist) will perhaps have something more specific in terms of historical spec vs. current. Interestingly, steels as they were offered originally often have changed over time depending on the conversation. For example, if there is a precursor to O1 or a whole series of oil hardening steels, what remains now may not be what was initially popular due to improvements or changes for other reasons.

You can also find generalized specs at steel suppliers.

If you want to machine O1 quickly, finding it in spheroidized condition (if listed) is a good idea. If you just want to grind and heat and quench bar stock, getting the steel in annealed condition should be better. Steel that’s spheroidized can be intentionally cooled very slowly so the carbides have “balled” to be larger and further apart. However, Starrett is spheroidized and before I knew that, I heated and quenched it in soy oil and the results were good. You can do better once you know a little bit more, but I’m not sure any woodworking tool user would notice.

Final Thought – it’s the Reliable Fairway Wood off of the Tee, Especially if You are a Maker

In the hardness sweet spot for me really the middle of the range, and 61.5-62 is about where I end up with a 400F temper, it’s like a reliable golf shot that scores well. Everyone always wants something for nothing, but O1 is a steel that gives you a fair something for something. And much of what’s in current woodworking tools gives you a little less than that fair “something for something”.

There’s nothing that O1 is really lacking in practical planing or chiseling, so it becomes the bar I judge other steels by. If I mention O1, like in the post about experimenting with W2 to make a large chisel, that there’s something I want a little more of vs. O1, it’s hard to describe if you’re not used to small improvements. Those mentions aren’t because I think O1 is something I couldn’t live with, but for example, if another steel may find its sweet spot in chisels a point harder with less alloying, I find that nice. Not differentiating for day to day woodworkers, though.

If anything, I think if you find you like Hock’s irons (but you may find that they nick easily before they’ve worn a little bit) or you want O1 from Lee Valley, but you find edge life short, it’s worth asking LV (who now has purchased Hock) why the irons aren’t offered at a target of 62 or 61/63, whatever is practical. In actual practical planing, i’ve found better life than when harder or softer, and chisels are far superior at 62 vs the low end of the practical range.