After writing yesterday about pigmenting the varnish, any beginning art student would probably say “hey, dum dum…you have to mull the pigment into the finish or it’ll be gritty”.

Mulling pigment also binds the pigment to oils if done in something like linseed oil. I haven’t done it – too lazy, but I’ve used linseed oil and pigment to paint things outside. I just mix them – it’s sloppy – as in the result isn’t that great, but if the oil goes on like flat paint soaking into the wood, it still looks fine.

In a fit of “you have to do it to experience it rather than read it and just imagine it”, I bought fine pigments from Rublev. There is a lot about making varnish bases for paints in Ralph Huff’s book. I think you will see something from Steve Voigt about it at some point, but there are things simply stated in the book that don’t make great sense -like making a varnish and then adding a similar volume of oil.

Once you do things in practice, that makes sense. I think I already said that brushing varnish can be a pain because it’s string or its adhesion causes it to pull all different ways when you’re brushing it. You can thin it, but it doesn’t lay out like lacquer does and it takes a little work. It’s a superior finish, but if we’re being reasonable, who here needs a better finish than plasticized lacquer? I don’t – you can repair it forever. But what I can’t actually do is buy it and then spray it here. It’s too obnoxious and I already cannot tolerate brushing lacquer fumes without getting dizzy and being off the mark for the rest of a day. No thanks.

At any rate, the book refers to “Grinding pigment in”. That makes me think of a vitamix, which would probably also work, but I don’t think I’m going to try it.

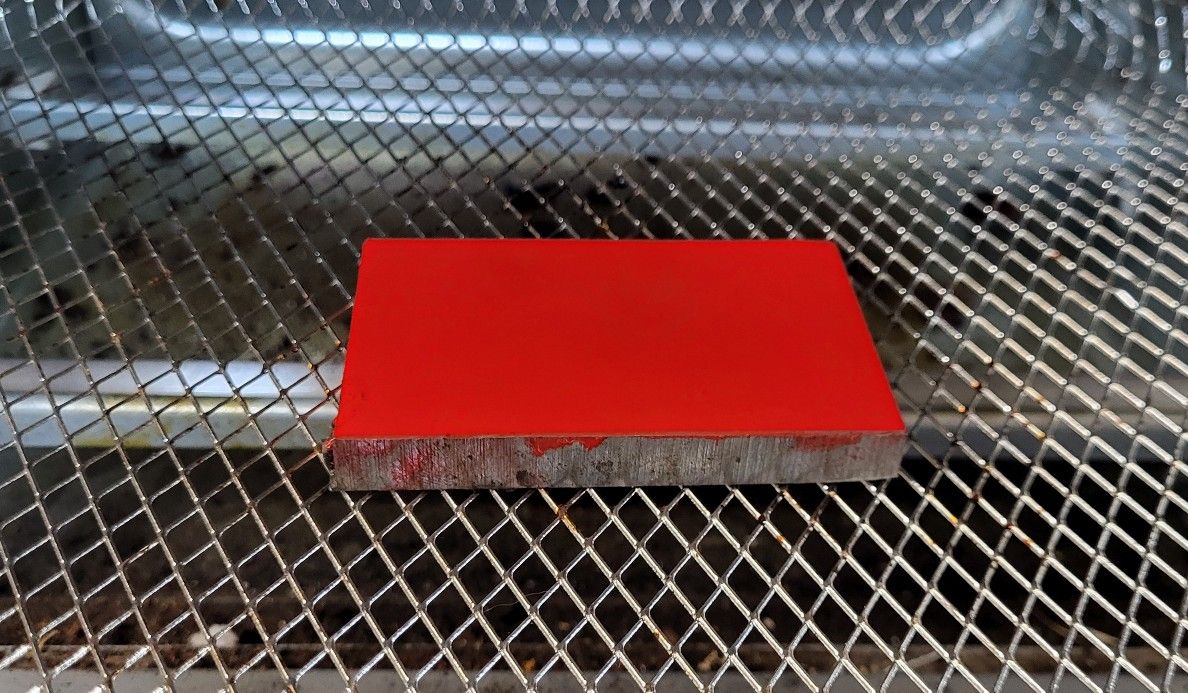

I assumed the little nits in my japanning trials were probably mostly dirt, but they’re more likely at this point to be pigment that wasn’t mulled, and taking a kiridashi – ok, not a real one, one that I made – and squashing the pigment on a hard plastic surface gets the big stuff out but not all of it.

Mulling is a step further and at one point from what I’m reading – of course I’ve got zero hands on – mulling was part of the process when buying pigment as an artist – the pigment needed to be mulled to make it finer, and then to bind it into a medium.

https://www.naturalpigments.com/artist-materials/how-to-make-water-based-paint

I haven’t read far about it and I’m not going to read that much. I’m waiting for a wide flat glass muller to show up so I can get on with this and then read. Do, then read, is always more effective than read, tell everyone you know everything and try it 12 years from now.

Mulling appears to be a lot of work, and it’s not done with high volumes of finish at a time. But I’m hoping to japan a few small metal items and I’d maybe come up with something else if making a varnish paint.

I often drone on about getting in contact with people who are doing things and learning from them, not people who primarily write about things. George Wilson changed my life as a two bit maker. I’m now two and a half, but just in how he thinks and talks – I am wired for that, but I was afraid it would be a waste of time.

I am making varnish only because Steve told me three times that you can actually make varnish – which I’d done, but somehow by the third, I’d noticed he said you could make better varnish than I’d made.

Now, I need to get out locally and see if there are artists supply places in Pittsburgh that sell pigments – because it’s pretty easy to blow $100 quickly on pigments, and some in person looking may be helpful. I think at this point, the fine pigment idea for varnish isn’t going to be a great thing for slathering all over stuff outdoors, but maybe there are more reasonable grades. I think I will not ever paint rooms in my house with paint I’ve made, but it’s not completely off the table.

By the way, we are, of course, lucky that these days, you can buy pigments that are already finely ground. I think from what I gather using cadmium red, what’s more the case here is that I’m breaking apart some particles that may be fused. I’m not going look at them under the microscope yet to see what’s going on. That seems a little undude, but if you have the bikini, wear it microscope, look through it.