I don’t know how many knives I’ve made. It’s not hundred, but realistically, if you’re going to make knives for other people to use in a kitchen, you’ve got to tackle using stainless.

XHP (V11) is stainless, but not very. Food acids will discolor it and it can be broken fairly easily by the uninitiated, which both probably have to do with why Lee Valley is the only using of the Carpenter XHP alloy that I know of. Those things don’t matter that much in a plane iron. I still read often how great it is for chisels, but anyone doing a comparison with a better chisel in the same task side by side, grinding and sharpening on top of that, would probably decide otherwise. Its attributes suit planing more than chiseling.

There are tons of stainless steels that you can probably heat treat in a forge. I use AEB-L. AEB-L is a fairly lower carbon steel, but it’s a matrix type. Carbon is between 0.6 and 0.7, and there’s no nitrogen or molybdenum to step up the sharpness. When I make knives, I’m doing it as an amateur and handing them out – I want steel that sharpens like a chisel. I have missed the mark on hardness with AEB-L and XHP before learning just how much open forge heat it takes to get them to decent hardness quickly, and the knives are usable, and at least as good or better than something like a Wusthof knife, and ground to a better angle. But they’re better yet if they are more like a chisel hardness. Nobody has broken a knife yet, so I’m not concerned about someone breaking ice with one and breaking one – I know they’re not going to break from regular use.

AEB-L can reach higher hardness than you’d guess – if you have a furnace and nitrogen. Larrin’s shown as-quenched hardness that’s in the 64 range and if you double tempered where I do – 340F, the hardness would probably still be 63. I am working with a forge and a freezer and that figure for me is 62 and 61, respectively.

This week, someone asked if I’d make them a knife that was 6″ long and more in proportion (not a copy, but proportion) like a large japanese petty knife.

I came up with the following profiles varying things I’ve got on hand, and decided to throw in a common classic parer type profile since I’ve already sent this person, a friend, a very thin small parer that’s almost like a razor. It’s a treat to use one of those tiny little parers that’s really thin at first, but it’s not practical for working on a cutting board, and feels a little dangerous in the middle of food or coring. It cuts too far too fast, and if friction sticks it and it releases, it could be a real problem.

All of these knives are .062″ stock and they’ll be slightly thinner. Two of them are 61 hardness post temper, and one is 60.5. I’m pretty pleased with what experimenting has brought in terms of results as I thought stainless would finally lead to me buying a forge. Instead, I’ve gotten one induction forge and now am getting a second as the first has some quirks and I’d rather assign it to part time.

If you look at the three knives, there’s some subtle differences between the middle one and the one on the right. The middle is straight through and I think it could benefit from more hand relief and it needs to be more pointy to do what a petty knife would do. I’ll see through finishing it, but the feel led me to make the one on the right figuring it’s just not good enough.

I generally put simple slab handles on in some kind of nice wood and then pin with 1/8th bronze or brass. I do that so that replacing the scales if something should fail is easy. If someone can’t find 1/8th bronze, often a clothes hanger will fit and if not, you can buy brazing rods and sand or scrape off the flux coating or whatever is on them. I haven’t lost a handle yet either, and use 180F epoxy, but something will come off sometime.

Good choice for wood on the handles is something hard with closed pores. Gabon ebony, macassar ebony, brown ebony, katalox – all work nicely. You can pore fill rosewood. I think I’m going to try a wood on these handles called Sapodilla, but not totally sold yet. it’s hard, and it will eventually be a mid brown, but it’s purplish when fresh, and not very dark. it’s far less work to shape a handle that’s softer wood, but it seems like it would spoil the effort.

So, with the steel, there’s no long complicated process. I want no decarb with AEB-L and furnace schedules will create it without neutral gas or something covering the steel. Instead, I use a piece of exhaust pipe and torches. We need to get the steel to somewhere around 1950 at least, and in a quick heat, maybe slightly higher. A big propane forge has no control without a muffle and a muffle means hitting a temp and sitting for a while to get there. And preheating all of it. No thanks.

this is my anvil area. The top of the anvil may look rusty from disuse, but I’ve quenched a bunch of stuff with brine lately, and it looks like that in a hurry and then I sand it off.

The induction forge would be a treat to use for this if it made enough heat, but induction forges are keyed to a depth, and that depth is beyond the thickness of a knife. It will heat these blades to about 1500 to speed preheating if that’s important, but the magnetic forces try to go further into steel than there is steel there, they hit each other and cancel out. Otherwise this forge will take something like a chisel and turn it into falling apart sparking globs in a little over a minute – chisels are thicker.

I don’t have everything lined up totally here, but I get a non-flammable stand for the torches, whatever I have available, and set one in the pipe there and lift the back curtain that’s there for dust control when grinding. There is no mass in that pipe, just kaowool. there’s a second pipe to the right of the forge that I have used as a liner for the kaowool, but it’s better as a former – use it to tightly pack the kaowool and then insert it in the larger pipe and pull out the steel pipe and you’re left with the form and no need to heat that piece of steel pipe. It’s a detriment to something like this.

I visually get the AEB-L to a point that is a really bright orange and a step away from yellow, then quench the top end in an oil quench and over to the anvil it goes to get plated between the anvil and the aluminum tempering plate, which does double duty as being a thermal mass in the toaster oven tempering things like longer knives. the little hole allows a thermocouple probe which is kind of needed if tempering is going to be really accurate. And it needs to be. Good heat treating, tempering and cool grinding all have to be had or the knife will be garbage can fodder.

AEB-L warps, and getting the top part of the quench done quickly yields decent hardness, and then there’s time to get the lower end finished and constrain the steel so it stays flat. This is also usable for making plane irons and so on. The top part of the quench must be fast, and the bottom end really cold, but there’s a little time to constrain and the item being heat treated in between both of those, along the lines of 10 or 15 seconds here, and I have noticed no difference in hardness by not just rushing the quench. Stainless doesn’t need the same speed usually, but that trick works fine with 52100 and other carbon steels.

the final step here, especially with stainless, is getting the blank into the freezer. I have a little cheap freezer, but it will get down to -40F. That’s not remotely close to liquid nitrogen, and it doesn’t do as much, but it does improve results half a point or a point vs. letting a knife sitting around air cooling to a higher temp at the end. Larrin Thomas had an excellent article on this – liquid nitrogen gives you some time to screw around and still see improvement. If the temperature drop isn’t as significant, then whatever you’re hardening needs to get into the freezer or bucket of propylene glycol cooled in the freezer really fast. I swipe stainless with a file on the way to the freezer. Since as quenched hardness for me is about 62 with AEB-L , if it’s short, it’s fileable. Even if it’s only a couple of points short. Just barely, but you can feel it. All in all, from first contact with the oil to being in the freezer, it’s probably less than a minute and I speed up the cool off by holding the knife against the frost in the freezer and then dropping it in.

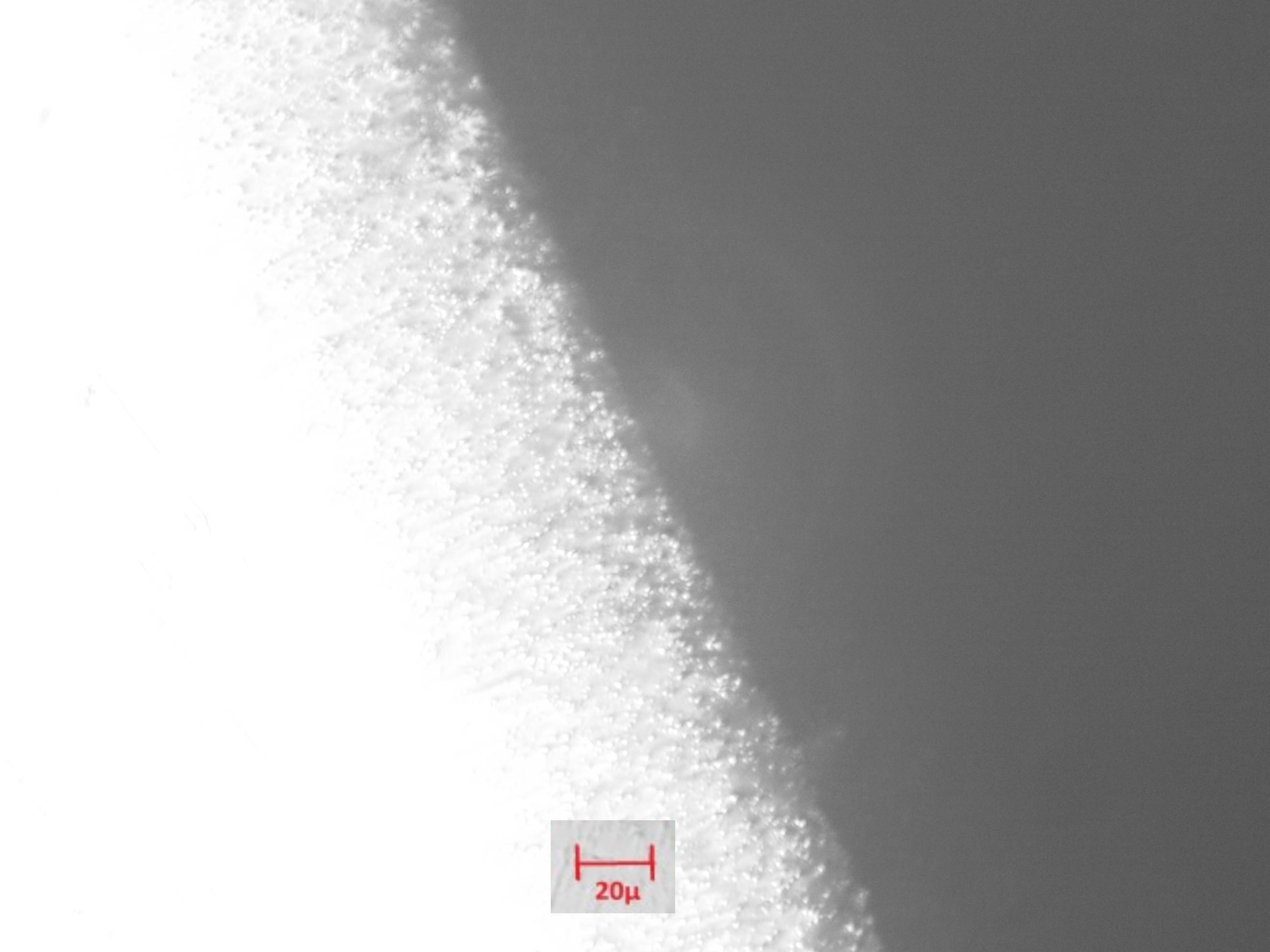

If you’re heat treating and not going to do any analysis other than checking hardness, you do at least need to snap samples and confirm your process doesn’t grow grain. This is a .062″ sample and it’s close to what I see with carbon steel. I asked Larrin what I should see because I thought maybe the high heat needed with bloat grain some, but Larrin said it should look similar. What the anomalies are, the shiny white dots, are probably artifacts more of my cheap hand scope. it’s hard to get a clear picture of these little samples and they break irregularly, so it’s not easy to get them in the metallurgical scope to look at where something needs to both be very level to the lens and also broken without any change in depth.

Whatever the case, this effort is fine and will make a good knife. The sample above is 62.5 which is about as hard as I’ll get out of the quench. could a furnace and nitrogen do better for a knife in practice? I don’t know, i think maybe it could, but I’ve made really thin knives out of AEB-L that are so thin I’ve accidentally bent them and then bent them back and given their hardness, that’s pretty good. And they sharpen well and hold their edge well, and the steel does fine in a plane iron. I don’t use it in plane irons because it seems like these ultra fine carbide irons don’t have the same feel as they dull.

While we can see the magnified grain here, the carbides do not cast a shadow on a plane iron when I wear away, so they are not visible and likely below 1.5 microns. The surface of the steel just looks like fudge instead.

When I asked Larrin what I should see snapping grain, he remarked there is no easy way to see carbide patterns and I told him my little trick – which is to set the chipbreaker on a plane so the shaving rubs the edge with force and exposes carbides. You can see the carbides below from 80crv2 steel. These are about as small as I’ve seen – if they get a notch smaller, they won’t show up. They won’t show up for AEB-L and often on older cast steel, they also do not appear in any quantity.

This is kind of a boring post, and it’s hard to make it relatable if you’re not doing the same thing, but it’s just another illustration of figuring things out and testing them.

Henckels sources “FC61” steel knives from Japan. Those are AEB-L, but they’re kind of expensive – between $130 and $300 per knife. it costs about $20 including the wood for me to make each knife, and about two hours. They’re not as complex – there’s no bolster or pattern welding, but there’s no bullshit, either. Humorously, the Henckels knives say “Kramer by Zwilling Meiji” and they’re made in Gifu, Japan. Probably by a separate contractor. They look nice enough, but the maker from Gifu could just be used without having to pay to use two more names and probably short the pay to the contractor. No thanks.

All of this is doable – the forge doesn’t need to be part of this and AEB-L doesn’t air harden easily when cut, so you can work with hand tools. You can shape the handles with a belt sander or by hand with files, but I guess it’s honest to say while it’s not difficult, there is some learning curve difficulty and this is one thing that I’ve gotten into where the hardness tester is immensely valuable in checking things quickly.

the stainless pipes – both the bigger and smaller are literally stainless exhaust pipe sections – the cheapest way I found to get something with some substance and strength in stainless.

A $225 “bucktool” belt sander and a spray bottle is enough to grind these into a finished knife without burning them – using ceramic belts. I do usually use a high speed grinder, though instead, but have done knives in stainless only on the 4×36 sander. This isn’t the same knife, but since I haven’t finished these knives, I figure a picture of a knife that was finished is in order – they’ll end up being similar to this. Understated, not expensively made and not expensive looking, but a small fine bevel and blistering sharp. I’m a little bit partial to hand finishing the sides not to a super fine finish for two reasons – one, they don’t instantly look marked, and two, if someone marks up a knife, then without doing anything else, you can always freshen the finish on these kinves by laying 400 grit sandpaper over a wood block in a vise and pushing the knife linearly across it. I don’t know why it bothers me, but I think it’s a shame to have a decent knife that is hard to freshen up once the knife gets covered with scuffs and little scratches.