I had (have?) a little problem with sharpening stones. It’s not a functional thing for woodworking, though I am probably better at sharpening than I would be without having this little “thing” with stones, and the microscope, and straight razor shaving, and sharpening scissors and axes, and ….anything. Even plastic things with an edge.

But from a lot of exposure, I can identify what’s run of the mill and what’s not. And what’s absurd in price (cough…shapton 30k, anything new from harrelson stanley – my opinion….and so on) for what you’re getting. Not that you can’t make something expensive to make even if the core parts of it are not, but remember you, you can go to 0.1 micron diamonds at low cost and a full pound of linde close graded white alumina at 0.3 microns was $60 the last time I splashed out. it’s so fine that it’s not very dense – it sits in a big tub something like 1/16th of the density of the actual alumina textbook amount itself.

Over time, I’ve kind of lost interest in waterstones because I think they aren’t as practical for most people. They seem practical early on with a guide, but they’re …well, not very convenient for a point and shoot type sharpener with skill. What do they do so well that an oilstone won’t do? Cut fast? They certainly don’t cut faster than a silicon carbide stone with the right oil to flush out particles, and they don’t cut a huge array of steels better than sprinkling loose diamond on a natural stone. Have you seen a waterstone that properly cuts CPM 10V? I haven’t. A slow but wonderful feeling very fine oilstone will cut 10V making it impossible to see under the microscope that it’s even loaded with vanadium carbides that are much too hard for aluminum oxide to cut properly.

Before I go on – there are waterstone I treasure. they all came out of the ground, and in some cases, people have traded something I’m fond of, sold me something maybe they sold because of my excitement, or given in exchange for advice or services. So, on the very slim chance you’re one of a very few people who has done that, I have those stones. They permanently reside here, and I guess when I’m dead, people can figure out what to do with them.

So Why is this about King?

The prince of a King I’m talking about is this stone:

Looks like a ratty old oxidized king waterstone, right? It’s tan.

The writing on the back gives this up as an oilstone. it’s vitrified as far as I can tell – like a Norton stone. It’s also really fine, but I think there’s a skin on it so I can’t tell how fine. It’s in no way, shape or form remotely similar to a Norton fine india and I’m pretty sure I have an old stone that is a norton ultra fine or someone else’s offering of the same. Norton has a stock number for a UF, and that’s the stone we’d all like to have, but I’ve never seen it for sale during the period of time I’ve been a woodworker.

I put some oil on this stone, and once I started using it, the oil went right in.

In fact, all of the Japanese oilstones I’ve gotten other than the ceramic mug type stones that are like a Spyderco white stone have not been oiled or pre-oiled. I’m going to take a shot at that with this one as soon as Vaseline arrives. I usually stand my ground, so I don’t keep Vaseline on hand.

Put differently, these are oilstones, but they seem to be sold allowing for use with water, and they work like shit with water – not the good kind of it, either, more like about as well as a cowpat functions as a frisbee. With oil, they are wonderful. They have a “softness” to the feel that is kind of like soft brick, but other than the white ones in a subsequent picture, they have some feel. I think if folks in japan were not so averse to using oil in stones, these would’ve gotten some footing as an interim stone where there just isn’t much good anything in waterstones -especially natural ones. And yes, I have had huge pure white whetstone size Mikawa nagura. they’re really neat, but they aren’t better than a lot of things that cost $25.

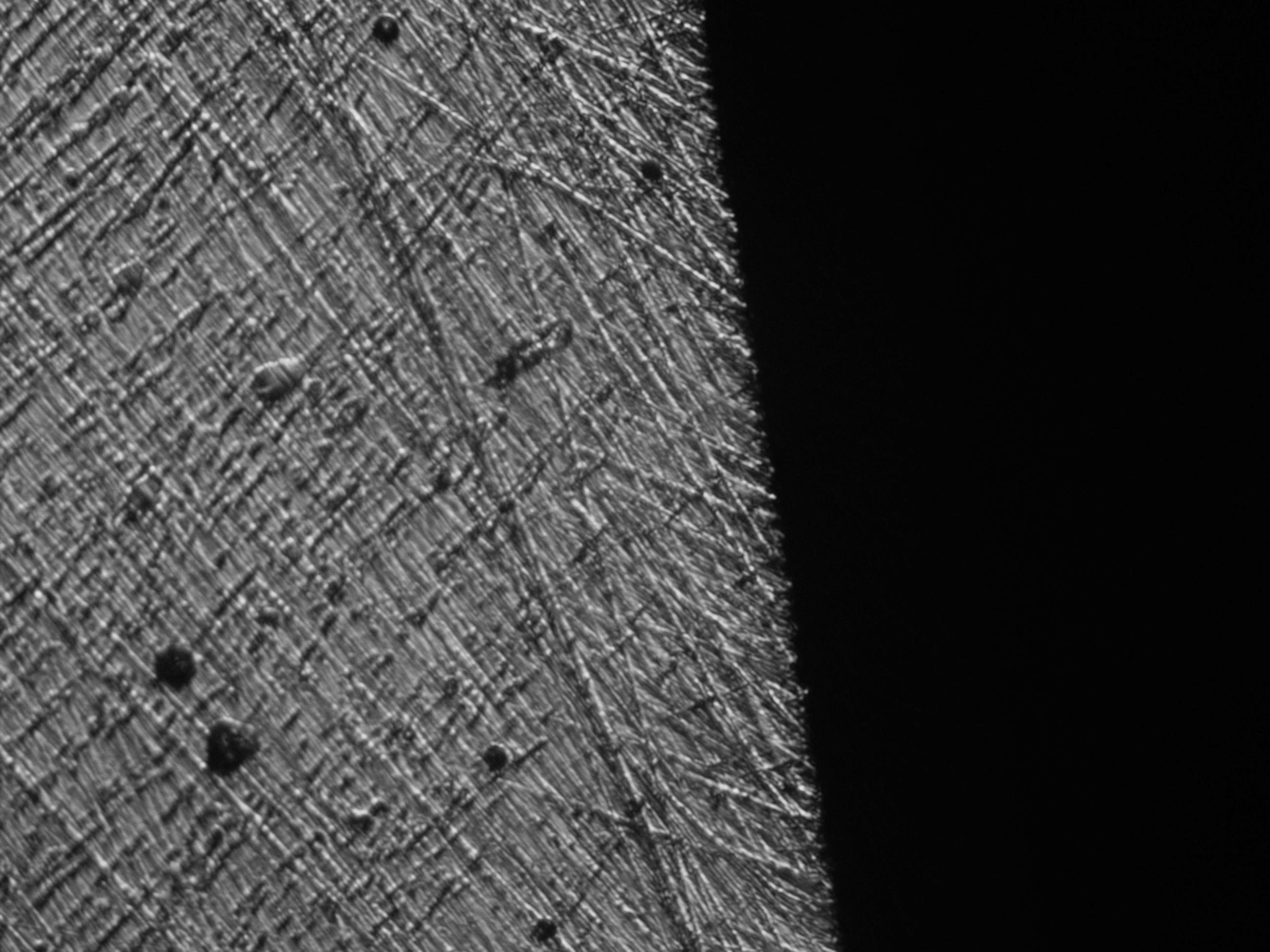

So, what does this do for leaving an edge? After I get some vaseline melted into this thing and then just oil for real, it’ll probably cut a little faster. As it sits, this is what the back of a chisel looks like:

It’s kind of hard to judge that this looks like, but the nature of the stone is it’s touch sensitive. The flat area is bright polish – brighter than 8k. The edge as I see it has no foil without buffing or stropping, just light teasing off of the burr, but it does also not look terribly fine. Just really fine, and it shave shair, but by the polish and the tiny burr, I expected more.

I wanted to get a close up look at 150x with the metallurgical scope, but it definitely is designed for reflective metal stuff, and things like stones absorb a lot of light and this picture looks decent, but i’m sure there is detail missing due to the scattering of the light.

There are no large particles in it, but how fine does the picture suggest it actually is? No clue. Surprised not to see more pore structure given the oil will disappear in it in a fraction of a minute. I have coconut and palm oil on hand, and the palm oil at least is probably pretty stable, but I don’t want to risk soaking the stones with that as it’d be stable for a couple of years, but will it go foul in the longer term? I’ll wait for the Vaseline, but I’m going to make a box for this thing. Vitrified alumina at this level of fineness is not common. Especially in a group of stones that was probably about $100 including shipping from japan. There were about 10 in that group.

Some from that group are here, and some are from prior stone groups. When I was in the throes of buying and sorting and redistributing vintage natural waterstones, I’d get some of these types of stones as a side show thing. As in, for the most part, I never really paid for them in a sense – I paid what I thought the other stones were worth, and the overall average for these probably is $5-$10 per.

The four gray and white stones here are much like a spyderco stone but larger. the top one and the one on the right both are the same – just the front does not say “barber oil stone” on it. they are alumina, very fine, but also are very slow. I see these all the time, but they often look little used and I’d guess for someone used to a waterstone, the operation of them would’ve been confusing. They are a tip of the tool stone.

The prince of a king is in the middle and trials of it made the face filthy. That’s just the way it goes. It’ll be dark once it’s soaked, and look less nice.

Top right is a middle india type stone, also 8x3x1 in size, or thereabouts, and it’s marked 300 vs. the white stones #3000. it is much finer than a norton fine india, so the number on it isn’t meaningful in grit terms that we’re used to. It was, perhaps, relelvant to the old grit scale where 1200FF or something like that was a barber hone abrasive.

In the years after those early 1900s barber hones were made, something changed industrially regarding how fine alumina is made. Precipitating may be the right term, and fine alumina could be had loose. Before that, something like a barber hone must have a glazed surface or it will chew up the edge of a razor in a hurry.

Some of the other red stones here are oilstones, or probably designed to be. Some with a dry vitrified feel and some have a hard but muddy type consistency if you can get something with diamonds on them to abrade them with an oil lubricant. They will go out of flat but not remotely close to as quickly as any Shapton stone, let alone king. The only work of significance I see done with any of these is little grooves from someone sharpening gravers, awls or who knows what – something narrow and hard. obviously, waterstones are not much fun for sharpening gravers or carving tools.

How do you Get These?

I’d never pay a lot for these. You don’t know what you’re going to get- it’s more like a box of cheap stuff and then you see if any is good. They are around in japan on Yahoo (equivalent to our ebay), but someone could want $80 for one, and the next person may sell a pile of them in a group of 20 stones for $60. Beyond just not having anything to return if you don’t like things, you can get a real nasty surprise after you win an auction when you find the proxy services seem to have suddenly lost interest in surface shipping really heavy boxes. A $60 lot of stones suddenly will have air shipping charges of $200. No thanks.

I’d personally put them into a category of if you happen to see one cheap on ebay, maybe. Otherwise, it’s just fun to me to see what was made in different eras, geographies or both.