In the prior blog post, I mentioned that 1095 knives are probably not 1095 steel alloy, and implied that what’s often asked on woodworking forums “Is this old tool O-1 or A2?”. The answer to the latter is in most cases, neither.

After finding 1095 to be unlikely as a plane or chisel steel due to poor toughness at high hardness, I looked around and finally found old stock being sold of one “improved” 1095. It’s called Sharon 50-100. This series of steels is at least three or four different alloys. 1-1.1% carbon steels with some chromium added, and for a B version, a small amount of vanadium.

And for the people lurching in their seats because they would never use chrome vanadium steels, only O1 or V11 – V11 has both chromium and vanadium in it, and O-1 also chromium in it with many of the variants from high quality mills also having additive vanadium.

The 50-100 variant that I was able to find was monstrously inexpensive – think $5.50 of steel to make an infill plane parallel iron with enough left to make at least two or three kitchen knives. It’s only available in one thickness, so no stanley plane irons and no chisels with it, which is kind of a bummer as it may have made a nice change up to the high hardness 26c3 carbon steel that I like to use. Once in a while, I come across someone who doesn’t like a high hardness chisel and there’s no real reason to make a 26c3 chisel, for example, and temper it down to 61 hardness. It excels being 63 on the low side at least, and up from there several points if you desire.

So, back to the irons. 0.145″ is OK for an infill plane iron – or maybe a Lie-Nielsen 8…..a plane I don’t have.

Making the Iron

Making the first iron, the only one I’ve made, I like to see what I can feel. By my estimation, the steel is spheroidized. This means treated in a way so that the steel is very soft and the carbides have been conditioned into little round carbides vs. the elongated types usually found in rolled annealed stock. It cuts like butter, and it won’t air harden while cutting and grinding. That translates to easy working, drilling and sawing.

From bar stock to finished heat treatment is about 45 minutes. I can’t tell anything from the sample other than it is spheroidized-like softness and there’s no feel of alloying like you’d get with highly alloyed steel. By the way, you can find information about spheroidized steel and its workability but sometimes-impediementary (new word!) properties for furnace heat treaters. The way I heat treat in a forge, it makes no difference and given the choice, I like starting from spheroidized stock.

The steel still has scale on it as delivered, but that will disappear just in the making of the iron and finishing of it later.

All in all, a delight to work with. I don’t care about decarb – that is, I don’t care if the outer layer is decarburized from rolling as it’ll be ground off or honed off in short order.

The iron, along with two O-1 tapered irons recently made, shown below. these could be perfectly finished to remove the marks and eliminate evidence they were hand made, but that’s kind of prissy. There’s already too much prissy stuff in amateur woodworking and toolmaking that aims at beginners.

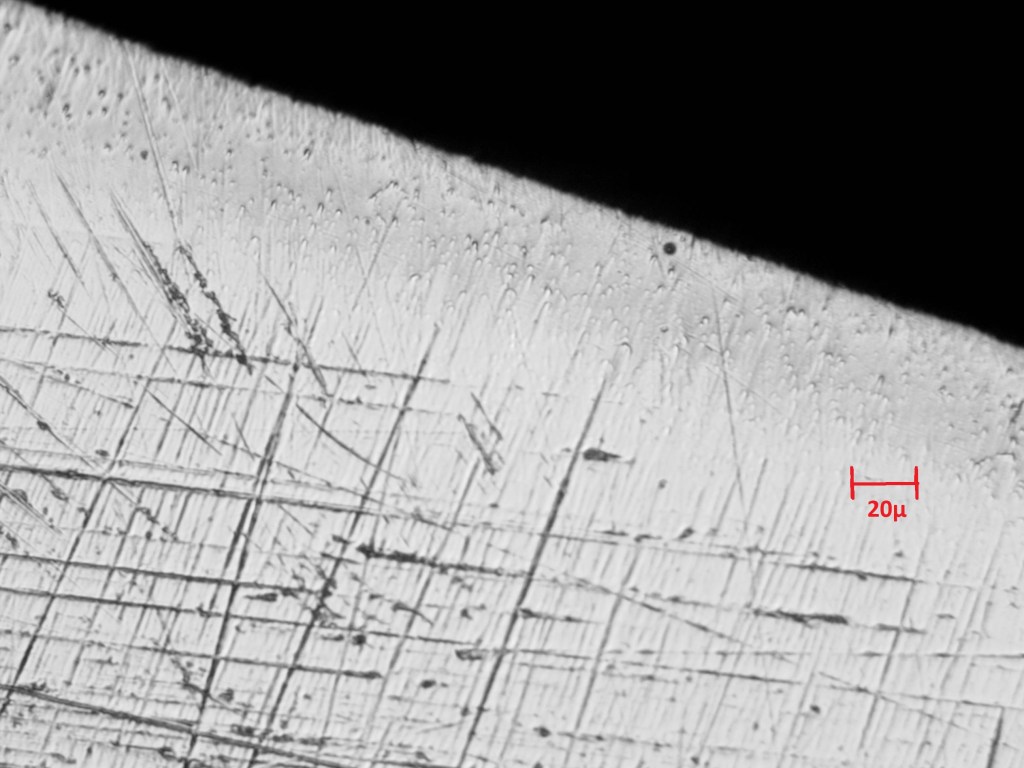

What I am hoping to see in this steel – the 50-100 steel – is a small array of carbides – I’ll show pictures of that in a second, as I have a method to see how they appear, how big, how many, how even. True 1095 itself has excess carbon and I would’ve expected to see iron carbides forming from anything over the eutectoid limit (0.77% carbon, or something like that). For the uninitiated, 0.77% is about the limit of carbon that can reside in a steel lattice before excess amounts start to look for places to reside. At any rate, my method to find the carbide pattern is simple – put the cap iron on the plane, use it and then take a 300x microscopic picture to see what’s not wearing away as fast.

The cap iron holds the shaving against the back of the iron and it neatly wears away a small cup in the top of the iron back. In a sense, it sands away the lattice of the metal leaving anything harder either to be broken and pulled out or standing proud. Whatever happens other than uniformity with the lattice itself, you’ll see the evidence.

Reality in practice, as I’ve found and later read about, isn’t as simple as the eutectoid limit “squeezing” excess carbon out into iron carbides. The reality is excess (beyond 0.77%) carbon can dissolve into solution and remain in the lattice. As temperatures increase in a furnace or forge, more carbon can dissolve into and reside in the lattice. Based on what Larrin Thomas has published in patreon bits, probably public now, 1095 does result in a lot of excess carbon in solution. This results in higher hardness, but lower toughness. Or at least I think it results in higher hardness as I saw an average of about 61.5 rockwell C hardness with O-1 steel and 63.1 with the basic 1095 alloy steel.

So, let’s see some lattice/carbide pictures. What follows is a comparison of 1095 and 50-100 showing that 1095 doesn’t seem to “seed” carbides, but the 50-100 steel has a nice neat even spherically shaped pattern of carbides. Yay! that’s a start. Hopefully, it will lead to a steel that’s a lot like 1095 on the stones and in the cut, but just without nicking. First, “real” plain 1095 steel:

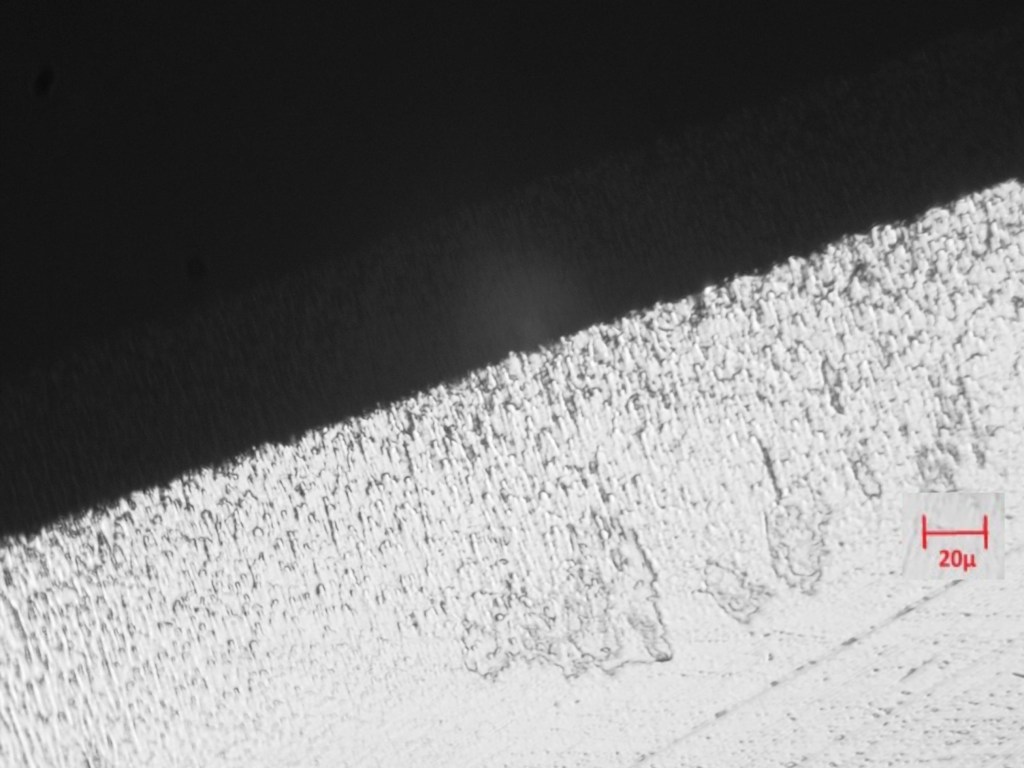

And Sharon 50-100 steel, roughly 1095 plus 0.6% chromium:

Both pictures are taken at the same magnification – light levels are a bit different and the cap iron was set a bit close on the second picture – not recalling the first, so the wear is shorter and steeper. The carbides in the second are the smallest I’ve seen. 26c3 has much more excess carbon, but it seems like fast formation of those carbides leads to less carbon staying in the lattice and despite the formation of those, 26c3 is tough and makes a good plane iron. It doesn’t last long in a plane, though – apparently iron carbides are good for hardness, but they don’t seem to have much of an effect increasing edge life. So I love it in chisels, I like it (26c3) in plane irons, but expect most of the beginner public would have fits with needing to increase sharpening frequency a little bit, no matter how easy it is.

Looking at 26c3, it doesn’t look like there are necessarily more carbides than 50-100, just that they’re larger. They are, however, smaller than something like V11. I no longer have a V11 iron, but I do have XHP, which is probably the same thing. If that’s true, Lee Valley isn’t in danger of anyone copying them. The steel is low availability and it’s expensive. Lee Valley is nearly providing a public service by offering their V11 irons at the price that they ask. I don’t care for the chisels having tested one – I can make a better chisel, but I didn’t go down this rabbit hole to start believing that somehow a chisel that is fine for a plane iron will be the same level of “yay” for a chisel.

What’s the Wear Resistance Like for 50-100? What Else?

I haven’t tested 50-100 against O-1. I suspect it will last less long, or fewer feet. Something that an experienced user won’t care about as it sharpens really easily. I think the edge life of 50-100 is probably about the same as a vintage mathieson or ward laminated iron, and that’s fine with me.

For comparison, 52100, a ball bearing steel, has much more chromium (1.5%) and bigger carbides and lasts about as long as O-1 in a plane iron. If you’re not that famliar with steels 50-100, 52100 – yes, I know these are like calling one guy Mark and another guy Marc and then talking about how different the Mar(c)ks are.

What about sharpenability – not just ease, but how the edge comes about. Sharpenability is as good as anything I’ve seen. Beware, this is about to go full cork sniffer….. though one man’s cork sniffing is another man’s blue collar practicality. 50-100 gets a click or two less hard than 1095 – I’d estimate 60/61 hardness in the test iron, and the grain is fine and uniform with the small carbides. There’s no perceived resistance to the stones – even O1 provides some feel of abrasion resistance compared to older steels. Creating a wire edge on a fine india stone to remove wear and get to finishing an edge is effortless – a matter of several seconds following the india with a worn washita stone.

When resharpening the iron above, I worked through these steps at a leisurely pace, but not dawdling. The total time including walking over to the buffer to buff strop after the washita – 47 seconds. The wire edge after the india stone can be teased off in very few strokes on the washita and the resulting edge would show a microscopic burr but none can be felt by hand. Pure joy in simplicity and ease, especially given it’s not harder than it is. That is, really hard steels often release their wire edge a little bit more easily on a fine stone, and this iron is hard enough, but it’s not icy hardness.

And the beauty of a steel like this becomes apparent to an experienced user if the lack of chipping that I’m hoping for also materializes. That is, it looks like it may be a good candidate to be a steel that maintains a constant undamaged edge. Sharpening probably removes about a thousandth of an inch of the edge and can be done in less than a minute. Add nicking several thousandths deep, and that’s sucky. For what it’s worth, good O-1 is also pretty favorable at this whole idea – sweet to use, but not too easy to nick and not much burden to deal with unexpected nicks.

I have more experience-based work to do. Initial impressions can be misleading and I think there’s a little left in the tank to go a click harder as I worked the quench routine with a bias toward straightness rather than all out hardness chasing. This kind of experience being my change of heart with V11 after being wowed in a standardized planing test planing several 5k’s worth of board length…..and then being unwowed with the same steel as soon as conditions even went to rough lumber planing.

So, confirming that the 50-100 iron will remain defect free just with regular sharpening – something I found V11 unable to do, and the same with house-made XHP irons – is all that’s left. And since it’ll never be commercially available as replacement irons….that’s perhaps the end of this pleasant journey. Hey – do I expect to make waves with 26c3 chisels? No, I’m making them and I think they’re better than anything commercially offered, but the way I’m making them isn’t scaleable.

Pictures of the Results of the First Grind after Making

I gave the iron a quick edge, but a good one, planed a little bit and then refreshed once. I always cut the bevel on a 36 grit ceramic belt, and I had no water available, so I cut the bevel on this iron using only my palm to cool it. This isn’t like your typical sandpaper, so don’t read too much into that. It’s designed for cool metal removal and excels at that. But fetching water would’ve been smarter and faster. 2 minutes instead of 5 minutes, perhaps, to cut the full initial bevel.

The point? I doubt it ever got too warm, but the first grind goes all the way ot the edge, and a 36 grit ceramic belt cuts deep and roughly. Only improvement would be ahead of this if any of the damage due to the rough treatment by the belt goes a little bit past the visible grinding marks.

One Last Speculation

Without doing a whole bunch of research, I would speculate that many of the older irons that are really a treat are that not necessarily due to the complete lack of existence of any other alloying elements, but rather that the ore shown to provide good results was then used. And whether it was known or not, what differentiated one ore from the next was not just lack of undesirable elements, but also lack of traces of desirable elements.

I haven’t had a chance to look much more closely at this because one of my tricks in my small bag now is to wear away some steel by planing and see what shows. I have a lot of older double irons, and expect that in general, they were not high carbon and probably shied away from the 1% carbon level staying more like 0.9% or a little below to avoid the problem mentioned above with 1095 – too much carbon remaining in the lattice. The one thing that could disprove this or may, at least, would be finding familiar patterns of carbides in these older irons – something I’ve really only seen in one laminated stanley 2″ iron.

Another woodworker has mentioned the chance to XRF (nondestructive analysis) some older tools to see what is in them other than carbon. The test does not identify carbon, but does identify most other things we would consider interesting. It is the same test used by two different people (at least) to find out what’s in PM-V11 when LV rolled it out. I had nothing to do with that effort and at the time am not sure I cared that much about it other than minor annoyance of not knowing what’s in the steel. The prevailing notion on woodworking boards, that the steel was a developed proprietary alloy, didn’t make sense to a few people who knew that LV’s cost figure for selecting the steel wasn’t high enough to actually fully develop a new alloy.

But, that’s just another example of overconfidence of the majority aided by lack of exposure or real experience. Sometimes it’s fine to just say “I don’t really know”. Even as much as I’ve gotten my hands dirty, I’m looking for outcomes. As for why they are what they are in each case, “I really don’t know” quite often.

Hi David,

Was wondering what kind of magnet are you using to determine if heated steel is non-magnetic? Any of the rare earth magnets loose their magnetism if heated above their Curie point ( I think its called. Usually in the 150-200C range…..) so what magnet is holding its own while being heated by coming in contact with what you are trying to test against? Just curious?…. Always interesting stuff you’re posting here!

LikeLike

Hi, John -glad to see you commenting. I have the magnet that I use on the end of a metallic tube and just either pull the steel out of the forge and check magnetism or stick the magnet into the forge quickly and then draw it back out quickly.

Either or depends on whether or not the steel is heating. Once I have a good sense of magnetism – now knowing that some steels have a slightly lower color temp when they lose it – then I don’t use the magnet too much. I’ve been learning what steels are really sensitive to grain growth and what others seem to actually like a slight overheat. 26c3 likes a slight overheat. 80crv2, with vanadium pinning the grain, seems to also show no evidence of grain growth – though there can be other things that drive hardness up and toughness down, like the actual final microstructure of the steel being overlapping plates instead a lath of fingers that grab each other more effectively.

Feel free to email me – I’ve got a set of chisel blanks in process for you but sent you an email earlier this year with a question that I can no longer recall. A few life things happened (nothing major, just interfering) that got in the way of getting time in the shop, so I didn’t finish the chisels yet and hoped you were doing well when I didn’t hear back.

LikeLike