When I compare pictures of grain in my tools to older tools, I often see larger grain in the older tools. The Ohio Tool was over the top, though – beyond that.

I lost my manners with old irons this past year and started nicking the edges, or in some case for irons I wouldn’t use, just breaking them to look at the grain.

So, when I compare pictures of my grain, there’s something going on in the older irons where the composition of the steel tolerates some grain enlargement, probably because the steel itself would be ultra tough at lower hardness.

The first ward iron I chipped the edge off of is probably 210 years old at this point, and I have to apologize, I don’t have a picture of the steel but to say that it’s almost identical in look to the much later iron I have a picture of below.

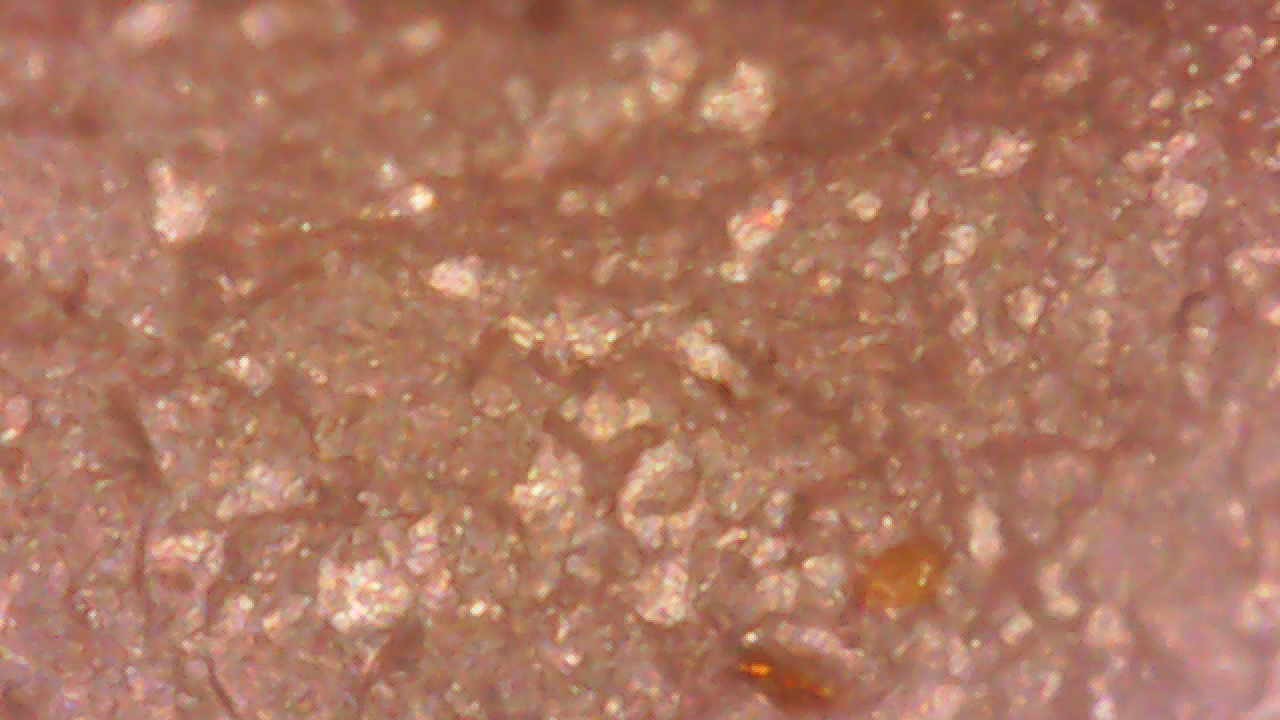

This is that Ward and Payne Iron (for the record, taper plane iron 61 hardness):

There’s something unfamiliar enough to me about this steel that I can’t say visual comparisons to mine are that relevant. And to some extent, Ohio Tool’s irons may be missing something a little if trying to compare them straight up. As in, it may be unfair.

In contrast to the ohio tool iron, partially due to hardness, but at least some due to grain, this 61 hardness W&P iron first deflected a lot and then in another section, I managed to strike it very hard and get a section to come out. it’s a very good iron under the punch test sensing how hard it is to get it to let go of some of its edge in the first place.

If I made an iron out of the steels that I use and the picture was as coarse as above, they would break too easily and have somewhat chippy behavior.

I thought knowing that the Ward and Payne grain doesn’t look as small as mine, it would be not totally fair to compare the Ohio Tool iron grain in the prior post to a modern steel that may not even be made from the same type of iron ore. It’s out of my area of expertise.

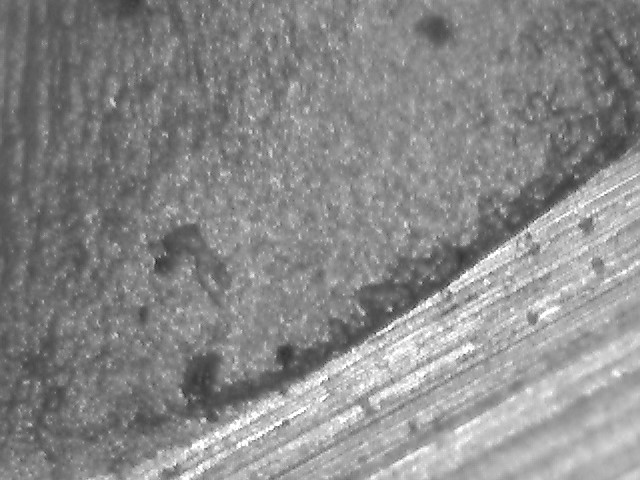

But just for reference again, here is a picture of that Ohio Tool steel iron:

It’s possible that those aren’t grains but rather agglomerations, but the force needed to nick the edge out of this was a tiny fraction of what was needed for the Ward. I don’t know if I’m going to venture into wasting my time with the Ohio Tool iron to temper it and see what the resulting hardness is. One thing is true on plain steel -if you push steel with a higher temperature prior to quench, even for a little, it’s easier to hit a high hardness target as the time interval to get to 900F or so widens, and when that interval at heat just above critical is 2 seconds, to get it to 3 or 4 is a lot of forgiveness.

The only way I know of to get actual grain boundaries and eliminate the guessing on these two steels would be Nital (nitric acid and ethanol mix) and polished samples. I’m just not looking to go that far. Nital can be dangerous (explosive) if some of the ethanol evaporates and I don’t have a separate lab building or something where that wouldn’t risk burning something down).

But I am genuinely curious. One, why ohio tool irons were never made better than they are, and two, why the Ward and Payne irons can look coarser than my irons but still be just as tough and very stable at the edge.

Mine again, for comparison, in case you don’t want to go backward chronologically (actually, this is another 125cr1 picture and I think I may have considered the grain a little questionable and given the iron away to a friend):

I don’t know what Ward and Payne used – but the 1.25% steel in this last picture, and even 1084, won’t tolerate too much in terms of enlarged grain. toughness can be reduced to a fifth or a tenth very quickly, and my first attempts at 1084 irons with somewhat enlarged grain were intolerable to use. It’s really high toughness, though, so making a 60.5 hardness iron out of it tempered at 400F and tiny grain is also annoying. It’s too tough and deflection damage will hang on – something you don’t want with plane irons and chisels. if damage occurs, you want it to remove itself so you’re not pushing an edge or deflection that’s really wide through wood.

If you’re curious about a modern commercial iron, the hock france iron that I broke and tested previously – in O1 – had grain similar in size to the 125cr1 picture above. I can shrink grain to a little smaller than O1, but can’t make the claim that it makes a difference. The Hock iron was a little chippy, but not due to grain. It was a little chippy because O1 is a low toughness steel and undertempering it just exposes that very quickly. I suspect Hock’s French irons were or are tempered around 325-350F. O1 comes into its own at 375F in my opinion, and if you can get a good hardness out of the quench, is noticeably better at 400F temper. That’ll knock down hardness from Hock’s iron by 2 points or so – I measured 64.5 on the one I had. O1 is ideally suited to 62/63..

So, anyway, I can’t totally solve the mystery here with the different looking grain pictures. Modern alloys look different under the scope. Iron carbides of size will start to show up and steels like O1 with tiny carbides (which still doesn’t result in good toughness) will look very fine.

All of these trivial things, even with the modern steels, will seem confusing until you’re working with the different steels. 1084, 1095 and O1 can just look supremely fine under magnification. the 1.25% carbon steels start to get some volume of iron carbide, which isn’t much of a threat to toughness like harder carbides are, and you can’t conclude much from each unless you’re comparing pictures of the same alloy.

Very likely that the four pictures here are all substantially different compositions. An XRF of the Ward and Ohio Tool irons would be interesting, to find out what’s different about them vs. something plain like 1084. 1084 is often suggested as being “like old steel” but if you make an iron from it and then use a Mathieson or Ward iron, they’re not the same, I’d say by feel, really not similar.

I’ve long wondered about the ore issue. My supposition has always been that ore makeup matters less with modern refining and achieving a particular alloy makeup is more a matter of economics in modern steel production. I didn’t come up with anything in a cursory online search, though.

LikeLike

I think it’s pretty well accepted that you can fiddle with most decent ores and get a very good result. The thing that’s harder to figure out or duplicate is the actual older steel, and then be able to describe why. I just don’t know enough about steel history, but am willing to speculate and possibly look stupid ….I’d guess the original ore dictated a lot of the additives but for carburization and obvious becomes very important in terms of cleanliness with regard to things like phosphorus and sulfur, but also benefiting from the favorable presence of elements that improve hardenability or toughness.

A reasonable starting point at guessing more probably doesn’t occur at least until some kind of spectral analysis that returns full composition including carbon (which XRF cannot). Not sure beyond that – but would assume something in the ore doesn’t match the alloying of plain steels now. Processing does change texture, though. We live in a world where everything is supposedly normalized away or annealed and then the same but in practice, that doesn’t get applied as well as implied.

LikeLike

I’m sure someone has looked at that more from a hobby level, like a university professor, etc, but it probably has little value industrially because it’s not as if a comparison of the two will drive a new discovery. Nobody is going to use crucible or plain steel now that the average customer for hard steel is production and die making or abrasive cutting like book or paper product making stuff. it’s a shame, as it would be interesting to see spectrum analysis of the older cutting irons along with a historical metallurgist fanatic type interpreting what it all means all the way down to what the chemistry was before forging, after forging and then in the final tool, etc.

LikeLike