In the last week, I’ve made five batches of varnish. I’m not sure how that happens, but the first four were quicker much lower temperature resins, so personal time involvement was only about one hour.

Last year, I made Amber varnish. I made it for two reasons. First, I’d had success with a resin (Madagascar copal) that I think most people will find difficult. Especially because it looks innocent – the resin is nice and clean without what looks like 6 digit years old bits of junk in it. The temperatures that I had to bring the resin to were surprising, and it seemed like a good jumping off point after that to do Amber. Amber’s melting points are a very wide range, but at the top end, some of the resin doesn’t melt until it’s over 725F. This is not particularly safe, and when I made the amber varnish last year, some remained unmelted in the pot.

It bothered me at the time that there weren’t any youtube videos running amber the way I wanted to run it, but there was a violin maker’s demonstration of it that resulted in a varnish for violins, but at a huge cost of pollution to the neighborhood and a whole lot of the resin was just cooked off leaving a small fraction of the original amount behind.

I was so happy that I got a good serviceable varnish from my effort that I thought it might be nice to make a video of the process and put it on youtube, but you can’t control who watches your videos on youtube, and the temperatures worked with Amber are seriously close to autoignition (resin meets air, resin catches on fire, etc). I don’t know what happens when the whole glom gets enough energy to ignite, but there are stories in older texts talking about how unsafe it was in an era where safety was 97th. I just don’t feel like putting it on youtube is a good idea because someone is going to get hurt, possibly worse, and possibly burning down property. The audience here is a lot more limited and…

….I am putting this up more for public record and would generally recommend you don’t think about doing it…unless you have already done it before or you have somehow worked your way up through making successful batches with madagascar copal, and I would suggest that’s in the same category if you are thinking you want to make varnish. You do things like making varnish and throwing half gallon jugs of gasoline in burn barrels at your own risk and I assume none of it. Nothing I’m writing here should be considered a how-to, rather a recorded record of a batch.

Too, what goaded me on with this is reading about Amber and having several conversations with George Wilson (who has also made Amber varnish – George can do anything, it seems) who mentioned that getting Amber past its first run results in a resin that’s really pleasant and cooperative. That statement is a bit of shell game – that “first” run, or melting and cooking of the resin before combining it with something or putting it aside as basically ready to use is difficult to complete without either catching it on fire or just turning it into something that’s burned ash.

I’m also goaded on because none of the older texts mention thermocouples and a lot of the discussion on the internet (violin makers and others) don’t talk about using thermocouples, but of course, I have k-type stainless thermocouples for tempering steel, and I have kawool on hand, which is handy for the cheap pots that I use with really high temperature resins.

But don’t do it. There will be one or five nutballs who cruise through google and might find this as a reference who have burned a few batches, and maybe they’ll be able to take parts of this and find something helpful. I’m less of a fan of the idea that someone will copy it not just for the danger, but because I’m guessing a little with the whole varnish cooking thing and doing what works. I wouldn’t dream of attempting this without knowing temperatures.

Should I say it about 14 times – never do anything inside with varnish that resembles cooking. The fumes that come off of running resins or even just heating linseed oil are disgusting, and from a chemist who seems to have a pretty low tolerance for chemical scare tactics, seriously unhealthy. When someone who dismisses some cobalt in japan driers as being overblown tells you that varnish fumes should seriously not be breathed, that means don’t breathe them. When George Wilson tells you that he made a mushroom cloud at one point in the past, that means you absolutely cannot consider making varnish anywhere that a mushroom cloud would do more than maybe get you in some trouble with the neighbors. There is enormous energy in the oil and resin, and if it is belched over the pot sides and is on fire, nothing good is going to happen.

Lastly, I generally make varnishes in the way they’re described in Holtappfel and I was the oil the way Joe R. said was an easy way to do it on a conversation Steve V. posted – just with water washes (three in my case). First, on the Holtzappfel varnish (I removed one named resin so this isn’t a perfect quote) “Amber and Copal are usually dissolved by fusing the gum and adding linseed oil heated nearly to the boiling point and then amalgamated by stirring”, and then at some point (a dangerous point, i’m sure) turpentine is added. Against some wise advice from people who know more than me, I have continued to run the oil and resins not and mix with the oil nearing 600F and the resins not at all cooled. So far, I have not had a varnish that didn’t turn out by doing this, and it’s not safe from a safety standpoint, but it’s safe in that you quickly get the oil and resin to link together and then you can decide what you want to do after that, as in, if you want to cook more.

Part of my point in relaying all of that is if you have read a lot about varnish and ask me questions, I probably won’t have a clue. If you use proper terms from the really old texts, I’ll have no idea what you’re talking about, and if you ask me about processes other than making both parts hot (separately) and then mixing them together, I won’t know that, either.

The Resin and Materials

Amber is for sale a lot of places, unlike some of the less common resins. But it handily comes from many of the suppliers in these little BB sized chips.

These are clean looking compared to some resins that have all kinds of not-varnish stuff on or in them, all the way down to tree bark and bugs. But you never know, so I wash them even though I think they don’t need it. A water wash would probably be enough but a light bit of lye sort of soaps the outside of the resins, and then you can rinse the whole thing until the outside isn’t slick. Color me stupid, but I imagine getting a fresh outside layer on the resin doesn’t hurt.

You can see how dirty the water is. I strained it through a dollar store strainer after this (dollar store items are good for varnish making – the mess left behind some things is easier thrown away)

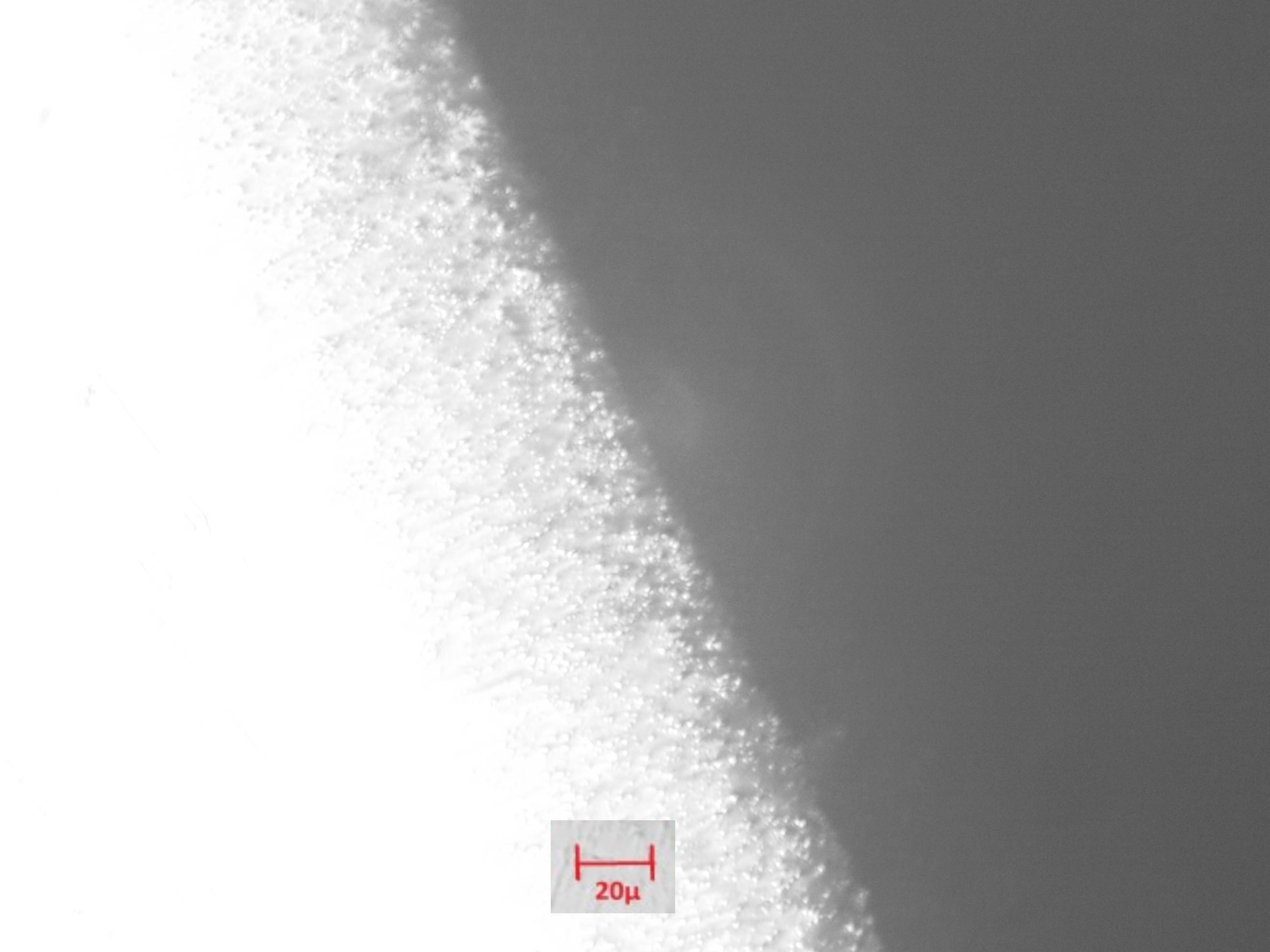

One of the challenges with the really high temperature resins is getting heat into the resin in the pot without just burning the surface. This isn’t a problem with stuff that melts at 400 degrees, but it is with stuff that melts at 675 degrees F.

To get the bottom layer of amber going, I’ve laid 2 oz of pine rosin on what is 10 oz of amber. There are recipes in some of my books that go further and combine high temp resins with rosin 50/50, but I’ve mentioned before and it remains true – i’m not much of a reader and mixing the two for now seems like “laying up”. I want some of the good stuff to try out and examine.

The rosin is almost like a thermal paste and as the temps get to the point that amber is melting, I don’t think the rosin is much more than a burned off layer. It doesn’t seem to be there in the bottom of the pot for long. At least you get to see my dollar store strainer. It’ll be used later when transferring the finished varnish into a jar.

To get this setup in a pot, I just flip the strainer over and the resin goes on the bottom. It probably doesn’t matter where it goes, though – it melts so easily it’ll end up on the bottom like oil.

I’ll bet there were ways to get amber hot (preheating it in oil or partially in oil or solvents or something), and later in nearly sealed vessels. Not an option for me.

At the same time, I weigh out 10-11 oz of washed linseed oil in a separate pot.

the proportions here are intended to come up a little short of a quart jar. 10 ounces baltic amber, 2 ounces rosin, 10-11 ounces linseed oil, 11 turpentine, though you’ll see later that a lot of the turpentine doesn’t survive the cook and more needs to be added later.

I got into the habit a while ago of making varnishes in about equal parts oil and resin, though some of the resin is cooked off, and both times I’ve made amber, probably 10-20% fails to melt and I don’t chase perfection at the risk of burning away or charcoaling the whole batch.

if you read around the internet, there are some surprising quotes about how much resin is burned off. Sometimes as much as 80%. There’s a reason, I don’t know what it is. I try to keep as much as I can and not cook it longer after it seems to be uniform and unchanging. More on that later.

There’s a bunch of stuff to carry – I pour turpentine into the jar that I’ll be using for the final varnish, and everything including the k-type thermocouple and reader goes into the box. K-types can go far hotter than we’re going, but a lot of the cooking thermcouples end around 570F and we’re going past that.

I’ve got an aluminum funnel, and not seen is a finer screen for inside of it as well as the dollar store sieve to be used as a large-trash sieve before the fine screen when pouring the hot varnish in the jar.

This stuff is all filthy and the pots are sometimes sticky around the edges- it’s just easier to put it in a box.

My cooking area is a fire pit. I walked outside and it’s windy. It may sound dumb, but if it’s windy, the pots will be affected temp wise, and this isn’t the time to have a cold side on a pot. So I use the same stuff I use to insulate the forge – kaowool, and wrap it around the resin pot sides and affix it with stainless “picture hanging” wire. Kaowool is a great insulator and it will withstand stupid temperatures. Whether it’s resin or something else melted on forge kawool – you can always just light the stuff on fire and burn out whatever is in it and the kawool will remain. You have to get into cutting torch ranges to do much to it quickly.

This is my setup. The dots on the lids are from testing drops of prior batches. If I run out of space, as inexpensive as the Farberware pots are, or whatever they are, used, I’ll just pitch them and get new. In reading early on, Holtzappfel or another book (can’t remember) suggested enameled cast iron pots are the top of the top for varnish making. They were talking about purpose made pots, and not cookware, but figure the same will be true. I have three that I bought used, and just haven’t used them consistently for anything other than heating oil. If you clean things, you may want to consider them – they are definitely better and more uniformly in temps along the sides.

I don’t remember reading anywhere to use kawool, but proposed it to someone else and they beat me to it. I also don’t remember reading much about using a thermocouple, but on easier varnishes, I adopted it for ease after testing a non contact thermometer vs. the thermocouple. Non contact types seem to be confused by pot sides, reflection in the oils and resins and smokes, and I wouldn’t trust them – especially for this. Reading 200 degrees cooler than actual could lead to skin grafts.

I am familiar with my electric burners. 10 oz of oil on 3.5 on the right side will eventually get to about 575F, and high temperature resins need almost all the left burner will provide. This cheapie goes from a couple of warming dots to 1-5 and then “max”. 5 will cook this resin terminally at about 650-700F. Another burner that I bought will not reach these temps – you can hear its thermal cutoff shutting it off. It stops around 550, which does nothing for us. No advice other than buy until you get what you need. Assume the burner will be destroyed and thrown away at some point, because it will. If something catches on fire on this one and it damages it, then I’ll get another.

I’m doing most of the heating here with the lids on – they are not air tight, but they are fully seated. There’s water in the oil. even with the lid closed, it will eventually steam out. I didn’t fully dry the resin here, but same effect, and just as with cooking, it will hit the lid and condense and dribble back down for a while. when checking to see progress and without the temp being too high, I leave the lid off for a minute or two to let as much out as possible. To have the resin hot and liquid and dribble water off of the lid into it could be disastrous. Even tiny rain drops will cause little tiny bits of hot resin to shoot out and they will burn you even if they are the size of a grain of sand.

After some time working the way up temp-wise, we’re here. How long? I don’t know. i don’t dawdle the cook up to temperature, but it’s also not on “max” because it’s too easy to burn the outside of the resin and start a process of just smoking and turning the whole batch into carbon. This is a feel thing and it’s easier learned with more cooperative stuff.

Once Amber starts to run, it smells hellish. Like burned tires and dead animals. I chose a windy sunny day because the smoke would not linger and I keep the lid on both for purposes of maintaining heat and to be a better neighbor. On a windless day, one will make enemies in a hurry.

I’m not attendant while this is heating up – I know the setup pretty well and know what will get the resin to 500F or so, so this is at the second check. the oil is not getting up to break temperature (just below 600F) at this point because the run will take a while and I just don’t care to smell it or try to push it that far in prep. The way I make varnish in terms of how thick the varnish ends up is to get the two parts prepared and combine them, and then after that, choose how long to cook. It can be done other ways, but this is easiest for me.

You can see that the pot bottom is at 615F and the resin is not in any hurry to melt. I put the lid on at this point and walk away for a while. You cannot hurry here and fall into the trap of wanting to blast the amber resin with heat – it will just create a char layer on the bottom and you’ll be lucky if you don’t ruin the whole batch. I’m treating it like an exploratory activity, slowly climbing until there is some resin appearing around the sides. I’m paying little attention to the oil at this point, but I know it’s safe to take the lid off now.

in the rare case that it rains as a surprise – because this will take several hours – I lay plywood over the top.

As the temperature increases, I remove the lid tilting the far side up and wear long sleeves and gloves.

At this point, it’s a waiting game -the resin is testing patience and begging to be smoked into a batch of worthless char. All in, the resin isn’t horribly expensive – it’s about $50 a pound, but that and the time involved is enough to discourage ruining it for no good reason.

There is a strong breeze from behind on the day of this cook, so I don’t wear a half face respirator. Usually it is mandatory – the amount of smoke and stink at this point is pretty mild, but it’s also carried away on the wind. It’s not to be breathed.

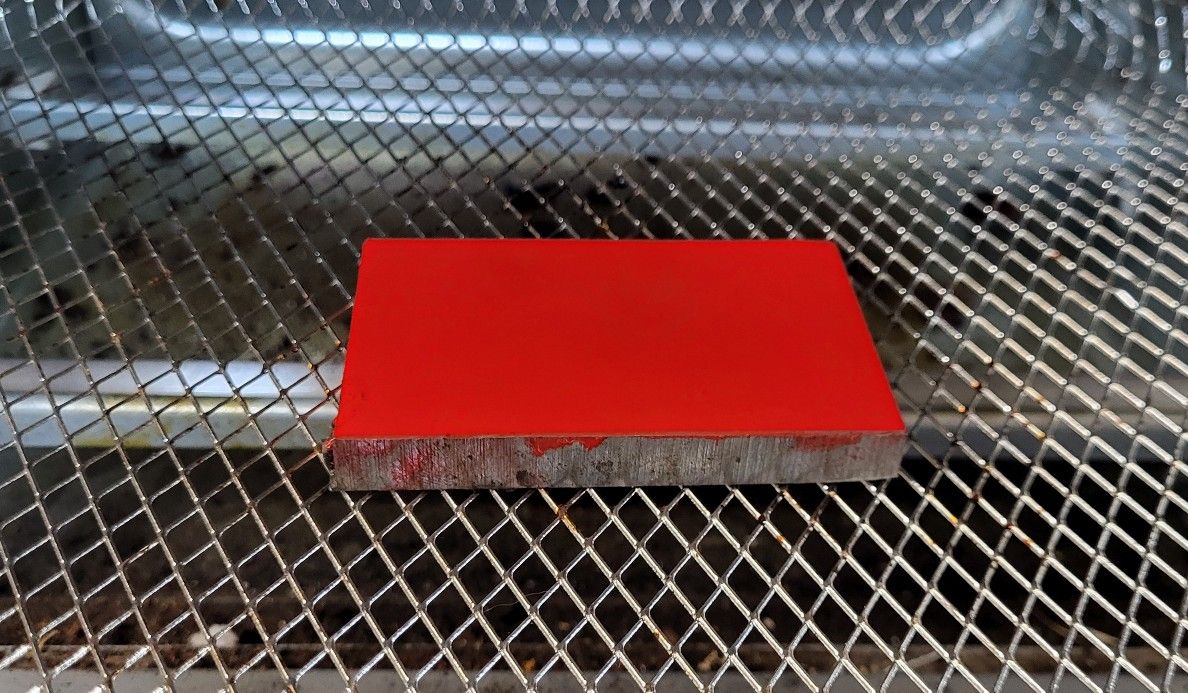

George Wilson tells me there’s all kinds of results you can get from Amber depending on the resin, and that he’s seen resin that has kind of an ugly grayish hue. The only place I’ve ever bought it is Wood Finishing Enterprises, and the result is the reddish brown color here. the little grains are all different colors. If you like sorting socks, you could actually separate them all and color match them. I’m satisfied with the mixed result. On dark woods like rosewood, you can’t see the reddish and on orangey red woods, I think the color is a strong enhancement of the base wood, and it’s in the varnish – not some faff-around experiment with dyes or stains. That’s a nice thing.

George Wilson tells me there’s all kinds of results you can get from Amber depending on the resin, and that he’s seen resin that has kind of an ugly grayish hue. The only place I’ve ever bought it is Wood Finishing Enterprises, and the result is the reddish brown color here. the little grains are all different colors. If you like sorting socks, you could actually separate them all and color match them. I’m satisfied with the mixed result. On dark woods like rosewood, you can’t see the reddish and on orangey red woods, I think the color is a strong enhancement of the base wood, and it’s in the varnish – not some faff-around experiment with dyes or stains. That’s a nice thing.